CHAPTER IX PALYNOLOGICAL STUDIES ON THE DEPOSITS OF THE DOUARA CAVE

Kankichi SOHMA* and Masako SASAKT**

* Biological Institute, Faculty of Science, Tohoku University

** Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, The University of Tokyo

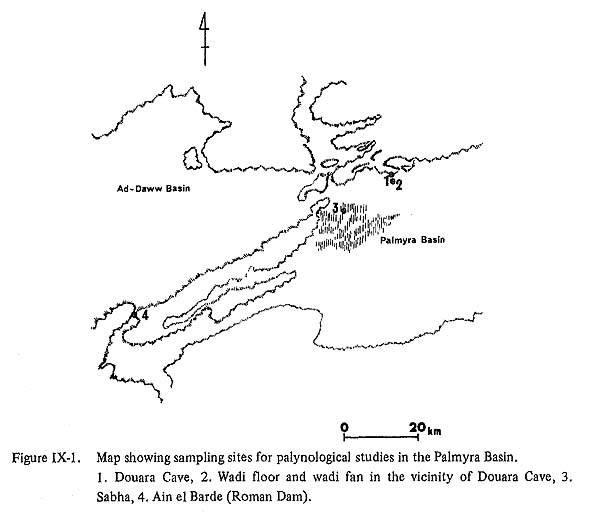

1. INTRODUCTIONThe scientific expedition undertaken by the members of the University of Tokyo for several months of 1970 was to obtain information in the field of anthropology, especially on "Neanderthal Man" and its related subjects, with respect to the area of Central Syria. A number of samples were collected from the surface soils and from the deposits of the area to get a clue to the background during the Palaeolithic period. The samples from the Douara Cave and the adjacent area were submitted to the writers for palynological study. The result of study is presented in this article. There are two palynological records from Syria, one is by van Liere (1960-1961) on the pollen-analytical data from boring cores in the Ghab, north-western Syria, and the other is by Niklewski and van Zeist (1970) who made a detailed pollen diagram based on a long core from the Ghab valley; they also described the vegetational history of the Late Quaternary of the area. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODSOf a total of 39 samples, almost one third of them yielded no pollen, while the rest except five samples which provided phytogeographical information of considerable interest, was too poor in pollen for a systematic study. The provenance of the samples reported here is as follows (Fig.IX-1);

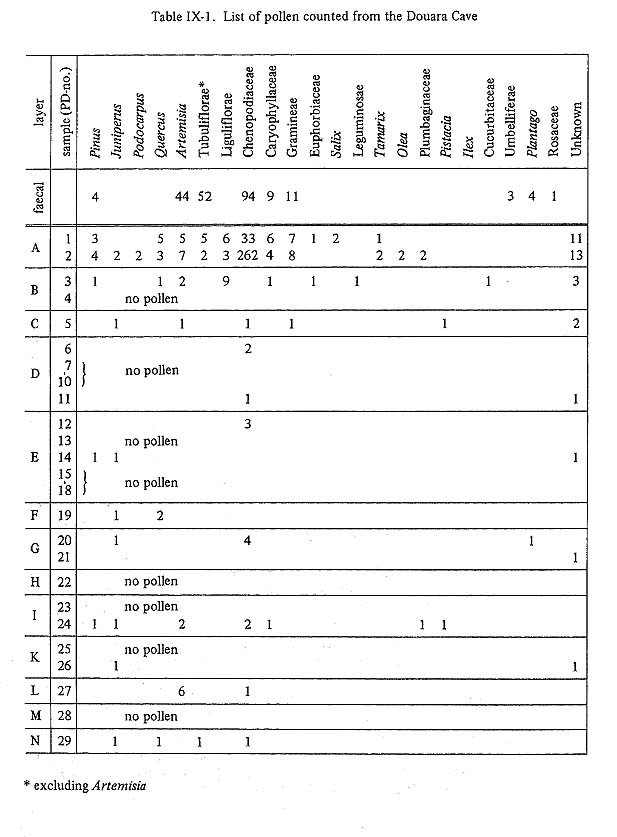

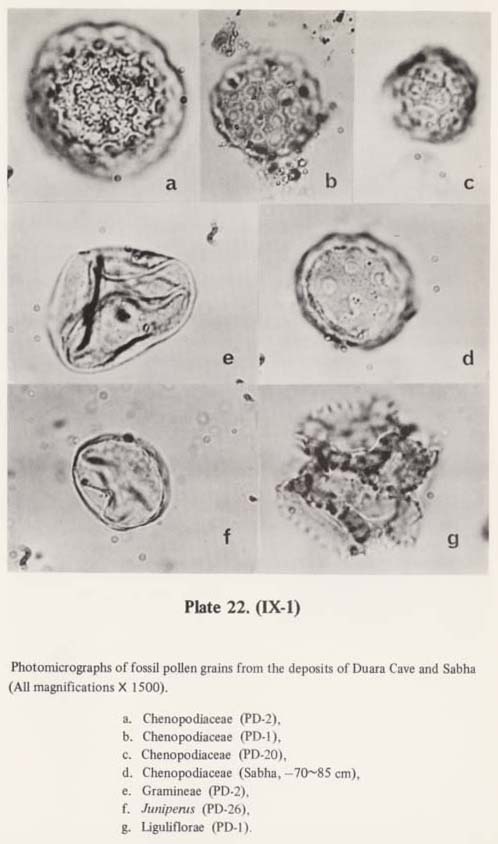

Since almost all of the materials consisted of a richly calcareous whitish or grayish to brownish silty clay, 10 percent hydrochloric acid was added to the samples placed in a large beaker which was then set aside until the effervescence ceased. Hydrofluoric acid extraction served to remove an amount of the silicates present in the sample. It was processed by using the standard techniques for extracting chemically resistant microfossils. The specimens were concentrated by a modified method of swirling techniques. Single-grain preparations sealed with paraffin were used exclusively. 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONThe results of the pollen investigation are given in Tables IX-1 and -2. some of the selected microfossils are shown in Plates IX-1 and -2. Unlike lake or marshy sediments, the deposits of the Douara Cave and the other sites yielded but few fossil pollen. For this reason, much cannot be explained.

The four localities investigated here are surrounded by the Syrian Deserts, where the vegetation is very poor. Most of the grains found from the samples must have been brought to the respective site by winds coming from the Palmyra Basin and/or the surrounding mountains. For the interpretation of past vegetations in the area of Central Syria it is indispensable to compare the present-day natural vegetation with the results obtained from the surface samples. It may be said that the palynological results of the surface samples from the Wadi fan, Sabha and the Roman Dam are influenced mainly by the actual floral composition of the adjacent area. Important evidences from pollen counts of faeces give information of the diet of mammoths (Kuprianova, 1957), giant sloths (Salmi, 1955; Martin et al., 1961; Laudermilk and Munz, 1938) and prehistoric man and his domestic animals (Troels-Smith, 1960; Martin and Sharrock, 1964). Mammalian faeces from the Douara Cave contain abundant pollen grains. It seems reasonable to assume that the sources of the pollen gains yielded in the faeces found on the cave floor are from the common plant foods, including flowers, pollen-dusted leaves and fruits ingested in the day's diet. Access to the cave is easy for the sheep, donkey and goat that now travel across the Palmyra Basin.(1) Of the 212 grains counted from the faecal sample, those of Chenopodiaceae and Compositae, including Artemisia, amount to more than 90 percent. Several members of both of these groups are dominant plants now on the hillside habitats throughout the area and are important as food source to those animals. During the season of flowering, a large number of the pollen would be swallowed by people and their livestock. The unusually high count of these grains in the sample may mean either browsing of the plants by the herbivore or recent pollination contaminating other foliages that were ingested. Though the climate of the Palmyra Basin will be discussed in another chapter of this report, the characteristics of the region is the hot and dry summer, and cool, wet and short winter. It shows a typical climate of the arid zone. The mean annual precipitation is about 100 mm and the mean temperature is about 19°C, at Palmyra. Western winds are most common in the region, at times reaching even storm velocity. The pollen flora of the sample nos. PD-1 and -2 from the Layer-A is marked by the high values of chenopods, nearly 40 percent for PD-1 and more than 80 percent for PD-2. Pollen grains of the Compositae including Artemisia, a xerophytic element, are also recorded, and may be interpreted as coming from near and around the cave site,, It is also quite possible that the grains of such herbaceous plants as the Compositae excluding Artemisia and Gramineae were at least partly local in habitat. Zohary's "Geobotanical analysis of Syrian Desert" (1940) provides general information on the vegetation of the area concerned. Moreover, useful information on the floral composition of the Palmyra Basin and its surrounding area is described by Post (1932-1933) and Mouterde (1966). A tentative reconstruction of the vegetation in the area under consideration can be inferred from the publications mentioned above. According to a personal communication of Mr. Khaled Assa'd to Prof. I. Kobori, some 26 phanerogams were identified tentatively during his visit to and around the Palmyra Oasis and Qasr et Hayr et Sharqi in Aug. 1970. These are as follows:

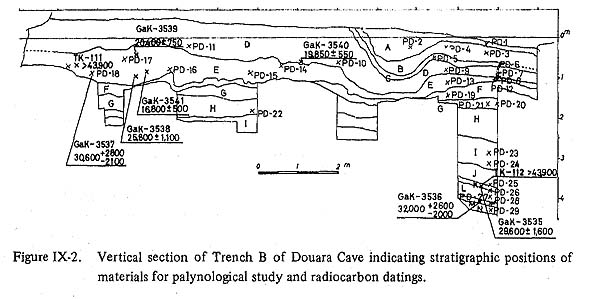

Here as elsewhere the wind-pollinated plants will inevitably contribute to the pollen to the deposits. Thus the pollen of the Chenopodiaceae, Artemisia and Gramineae can be expected in any of the pollen samples from the vicinity. On the other hand, pollen of locally growing Compositae excluding Artemisia, Caryophyllaceae, Leguminosae, Olea, Ilex and other insect-pollinated trees, shrubs and herbs will be scarce or absent in deposits. In the Ghab valley Niklewski and van Zeist (1970) pointed out that Artemisia and Chenopodiaceae are particularly indicative of dry steppe vegetations and not so much of alpine vegetations. The situation is also applicable to the Palmyra Basin and the site of the Roman Dam. Potter and Rowley (1960) found that in an arid grassland-woodland region of New Mexico the grains of Gramineae were under-represented both in the atmospheric pollen rain and in surface samples, while the pollen grains of Chenopodiaceae-Amaranthaceae were found abundantly. These behaviours of the pollen of Artemisia, Chenopodiaceae and Gramineae are comparable to those found from the surface samples of Roman Dam, Sabha and the Layer-A in the Douara Cave. Another pollen group of wind-pollinated plants that grow in abundance on the mountains of higher elevation is dispersed to great distances by wind. In the Douara Cave and elsewhere the pollen of Pinns, Juniperus and Quercus belong to this category. Long-distance transport of Podocarpus pollen found in the Douara Cave is also likely, although Podocarpus grows much far distance to the site than do the other conifers (Bonnefille, 1969). It must be stressed that in the samples from the Layers-K, -F and the upper part of the Layer E, there were found no pollen grains of Chenopodiaceae and Compositae including Artemisia. Some trace of the occurrence of the Juniperus pollen in these samples suggests that the tree may have been more common than at present under natural conditions. In the area of Syria and Lebanon several species of Juniperus are now found at the elevations between 600 and 1800 m associated sometimes with Pinus and Quercus (Mouterde, 1966; Niklewski and van Zeist, 1970). It is likely that during the deposition of these layers the climate may have been cooler and less drier than that of to-day. In this connection it should be mentioned that the pollen of Juniperus was seriously under-represented in the moss and lichen polsters as well as in the alcaline clay soil (Potter and Rowley, 1960; van Zeist et al., 1968-1969). The calculation of the ages based on the radiocarbon dates is shown in Fig. IX-2. For a comparison with the results obtained from the Douara Cave those of the other areas of the Near East must remain very speculative. Thus a detailed correlation with these cannot be made. However, it is likely that in the pollen-bearing sediments covering part of the Late Quaternary of the Palmyra Basin climatic fluctuations suggested by the pollen sequences may not be contradicted with those from other areas as Greece (Bottema, 1967; Wijmstra, 1969), Turkey (Beug, 1967), Israel (Rossignol, 1962; 1963), Syria (Niklewski and van Zeist, 1970), Iran (van Zeist and Wright, 1963; van Zeist, 1967, Wright, McAndrews and van Zeist, 1967; Wright, 1968) and Iraq (Solecki, 1963). As was stated earlier, most of the samples were too poor in pollen for a systematic study, and almost half of them were generally without any pollen. With regard to the problem, Faegri and Iversen (1964) have stated; "Various types of sediments are generally without any pollen. Slightly calcareous shales may still have pollen grains, but these are often corroded and difficult to identify. Generally speaking, limestone formations have little or no pollen, though certain types, e.g. paralic limestone, may be rich in pollen". The scarcity of pollen in the deposits may be due mainly to three reasons. In case in which no or poor plant cover had developed, great quantities of pollen may not be expected to occur except for the grains subjected to long-distance transportation. If corrosion or destruction of the exine has proceeded so far, during fossilization or after, the composition of the pollen flora will change and/or the pollen grains will disappear eventually. The third case, in which the depositional rate was rapid and enormous, will appreciably influence the pollen accumulation. The question as to whether the small occurrence of pollen presented in this study was due to a poor plant cover cannot be answered by a single formula. However, it may be certain that the deposits in the cave have provided some evidence to elucidate special problems of palynology. Note:(1) According to a personal letter (Dec. 9, 1972) of Mr. Khaled Assa'd, Director of the Palmyra Museum, to Prof. Iwao Kobori, University of Tokyo, one of the English officers set out camp in the cave, no more than one month, during the second world war, and some Beduins (Omor or Sba'a tribes) use this cave as a shelter during the winter months. BIBLIOGRAPHY

|