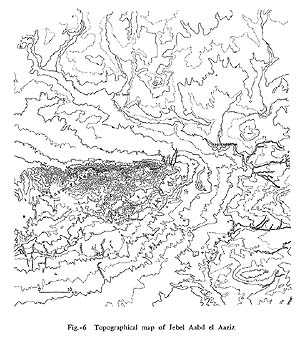

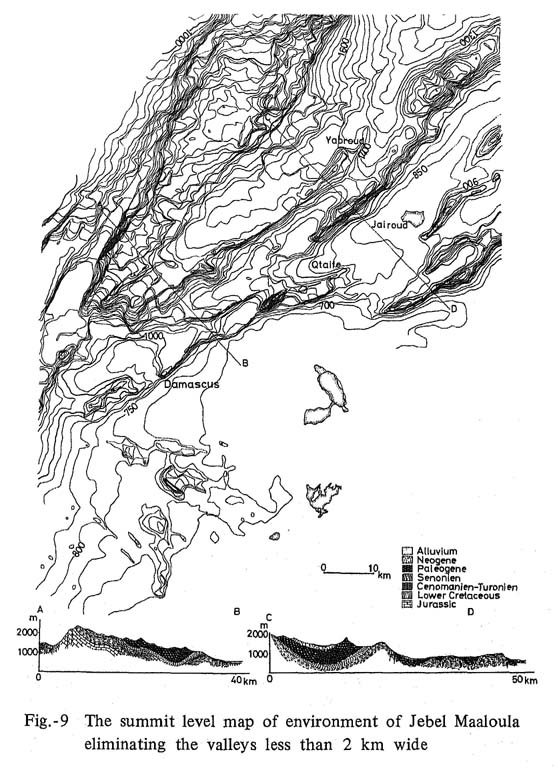

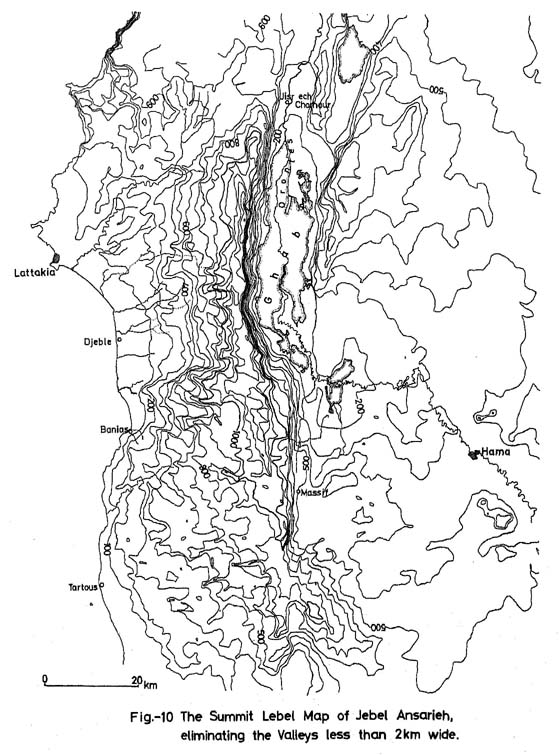

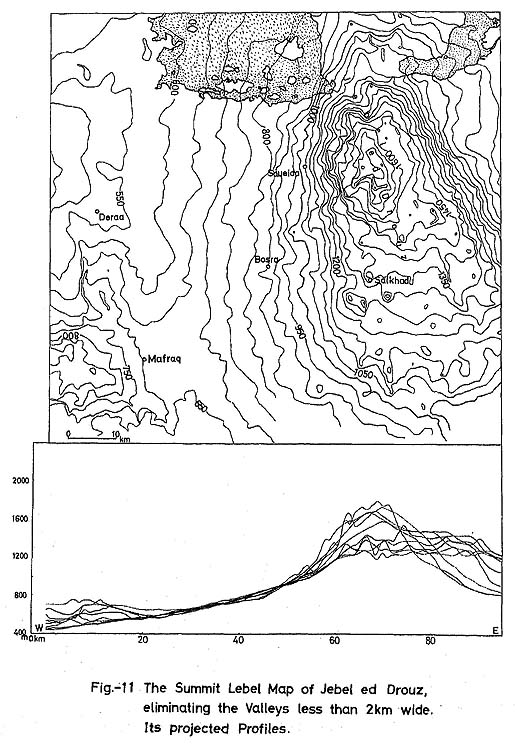

Since our object was the discovery of cave sites, we investigated mainly Jebel Aabd el Aaziz (Fig. 6), Palmyra region (Fig. 8), Jebel Maaloula (Fig. 9), and Jebel Ansarieh (Fig. 10) and Jebel ed Drouz (Fig. 11),

Fig.-6 Topographical map of Jebel Aabd el Aaziz |

Fig.-8 The Summit Lebel map of Palmyra region, eliminating the Valleys less than 2km wide |

(a) Jebel Aabd el Aaziz

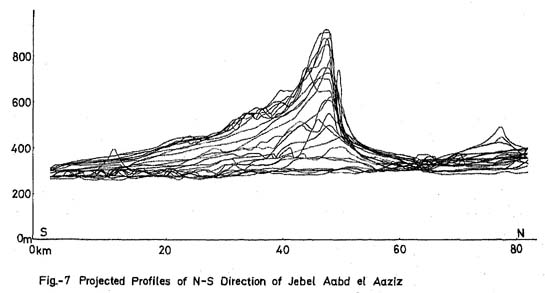

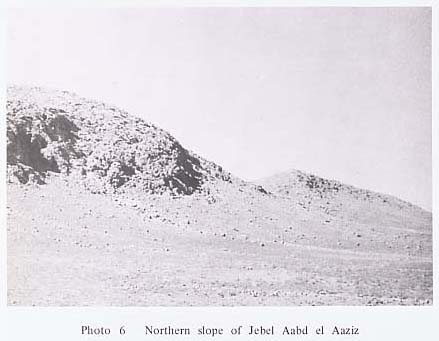

This is a block mountain between the Euphrates and its tributary, Nahr Khabour, in the northeastern part of Syria, running in an east-west direction for over 60 km and from 10 to 15 km wide. Its geological structure is an anticlinal mountain, continuing from Jabal Sinjar in the western part of Mosul in Iraq. Its highest peak is 920 m the mountain does not undulate much. The main ridge of 700 to 900 m in height is situated in the northern part. As is clear from the northsouth direction projected profiles in Fig. 7, the northern slope forms a steep cliff of 350 m height, while its southern slope is gentle, with less than 10°. The wadis are shallow also, and are not suitable for cave formation. The obsequent valleys, which erode deeply the steep cliff of the northern slope, penetrate deep into the southern slope with headward erosion. For instance, there are Wadi Marhlouja, Wadi Soussa, Wadi el Khazne, Wadi Rhara, Wadi Jaafar, etc., all running north. Due to erosion of the wadis and weathering, the steep cliff recedes with considerable speed, and the slope which continues on from the edge of the cliff ranges from 20° to 30°, and boulders with maximum diameter of 5 m and average diameter of 40 cm a cover the bedrock for about a 5 m thickness. The slope below it makes a clear knick point, dipping toward the north with less than 5°. The deposits farther away from the steep cliff, are finer, and 100 m from the cliff the average diameter ranges between 6 to 8 cm. Wadis erode the upper steep slope 5 to 10 m deep, but less in the middle gentle slope. In the lower level, they become a flat surface with less than 2° dip toward the north, and there are fewer wadis and they become shallower (Ph. 6). However, the thickness of Pleistocene deposits reaches 75 to 110m near Tell el Rhara, although the difference in the thickness has nothing to do with the topography. From the above-mentioned reason, our investigation was chiefly on the area along the wadis which cut the northern slope. Near Cheikh Aabd el Aaziz, Cretaceous clayey limestone, marl, and conglomerate from badland topography, and cave formation is poor. Therefore, we investigated chiefly the Eocene organic, compact limestone area, most widely distributed in the northern part of the mountains. This area, which rises symmetrically, because of the fault system running in an east-west direction, has deep eroded valleys, but cave formation is poor. However, there is a great quantity of flint scattered all over the slope next to the steep cliff. The investigated area is the summit of Aabd el Aaziz mountain ridge in the east, to Wadi Jaafar in the west, covering every wadi and northern slope.

(b) Palmyra Region

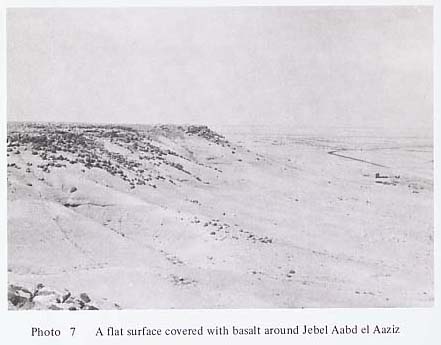

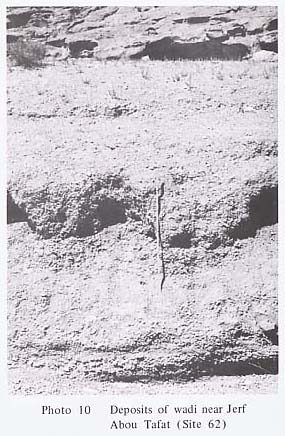

The Palmyrides, which branch out of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, consist of several mountains which run in a northeast-southwest direction, as partly shown in Fig. 8 (Ph. 8). The altitude of the mountains themselves is 1,000 to 1,300 m and the differences of altitude at its foot reach 500 to 700 m. Although there are two paralleling mountain ranges near Palmyra, in the rest of the places it is only block mountain and does not form a range. Besides, since this is an inland area, its drainage pattern is not clear, and base level varies depending upon the location of the mountain block. The center of this area is Jebel Abou Rejmeine, 1,350 m high, Jebel el Marah, 1,250 m high, and Jebel el Abiad, on which we placed the most emphasis, is 1,100 to 1,150 m high, and all these mountains are accordant. Geologically, Jurassic, Cretaceous limestone, clay, marl, dolomite which form folds and faults make up Jebel ett Taniyet Sahle, Jebel Haiyane, Jebel Qettar, etc. which constitute the main range of the Palmyrides. Jebel Abou Rejmeine, Jebel el Abiad, Jebel ed Douara, etc. are lower than the main ridge, and do not form a clear range system; they consist of Paleogene-Neogene limestone, conglomerate, clay, sandstone, and marl, with some foldings. However, the newly discovered sites which we investigated were nothing but small caves and shelters made of Paleogene limestone. This would naturally depend upon the condition of the area where the caves were situated, but it might also indicate that in connection with the quality of rock which forms caves, Paleogene limestone was more suitable in this area. The prehistory of the Palmyra region has been unexplored. It is a wide area, and therefore we carried on quite detailed investigations around the southern slope of Jebel Mqeita (Ph. 9) (Ph. 10), Wadi ez Zkara drainage basin, Jebel ed Douara, Wadi el Ahmar, and Dahr Rouaissafe Abou Fares. Opportunity was given us also to investigate a few Tells around el Kaum, northeast of Palmyra. Dissected fans with different levels were frequently found below the steep cliffs of Jebel Mqeita, Wadi ez Zkara, Jebel el Douara, etc., offering an interesting area in which to study the relationship of climatic change, geomorphic development and prehistorical remains in the Pleistocene.

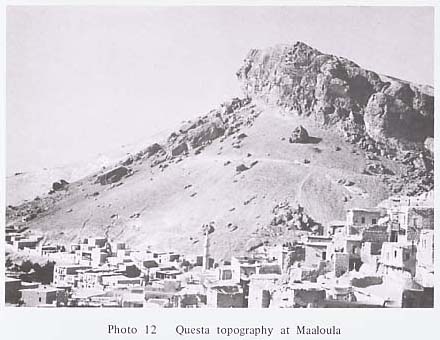

(c) Anti-Lebanon Mountains Range

Jebel Maaloula, Jebel Chemal, etc. which branch out of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains near Damascus, are called the Palmyrides, and run paralled with the main range up to the neighbourhood of Nebek. The Anti-Lebanon Mountains are 2,000 to 2,600 m high, Jebel Maaloula 1,800 to 1,900 m high, and Jebel Chemal 1,600 to 1,700 m high. All of these mountains are accordant, but farther from the main range, the height drops, and Jebel Dmeir at the southeasternmost part is 1,000 to 1,100 m high. As shown in Fig, 9, they form Questa topography (Ph. 12). Every mountain is extremely dissected. But the base level in the inland drainage basins naturally varies depending upon where it is, so that even if cave sites arediscovered, it is extremely difficult to determine their geological age. Geologically, Cretaceous, Paleogene limestone, marl, dolomite, sandstone, are distributed in belts, just like the mountain range. We investigated Nahr Barada near Draij along the Wadi el Rih, many eroded valleys on western slope of Jebel Maaloula, and Wadis on the northern side of Skifta Valley in Yabroud.

(d) Jebel Ansarieh and Ghab (Coastal Area)

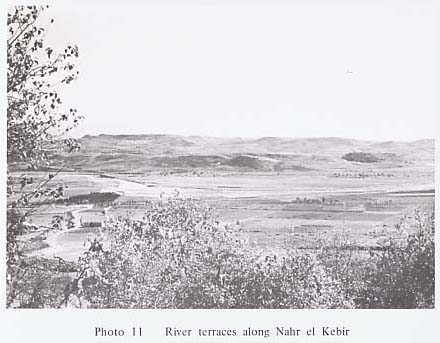

Jebel Ansarieh are mountains which run approximately parallel with the Mediterranean coast from the border of Turkey, and are separated from the Lebanon Mountains by the depression of Tripoli-Homs. In this area, too, just as in the case of the Lebanon Mountains, the main ridge is situated in the easternmost part, and falls sharply to the lowland called Ghab, which intermittently continues from Bekka valley, by a clear steep cliff. Reflecting the geological structure, the topography gently slopes down toward the west. The area north of Nahr el Kebir, which flows to the south of Lattakia, consists of Triassic olivinite, peridotite and serpentine, accompanied by intensive folding and faulting. As shown in Fig. 10, theyfrom 400 to 600 m high mountains. The mountains in the north of Banias are 1,000 to 1,500 m high, and Jurassic dolomite, limestone, Cretaceous limestone, clay and dolomite form anticlinal ridges. In the depression between northern Jebel Ansarieh and the mountains consisting of Triassic rocks in the north of Nahr el Kebir, sedimentary rocks of Miocene transgression are found, and downstream, there are thick Pliocene sediments. The Nahr el Kebir flows in the middle of a syncline, developing three river terraces in the downstream area. Volcanic activitysouth of Banias caused the flow of basalt during the .Pliocene, so that the topographybecome complicated, but as a whole, it dips westward. In the center of Ghab, the Orontes runs north. Because Pliocene basalt flow is dammed up at Jisr ech Chorhour, it had become a swamp, but now a drainage arrangement has turned it into excellent arable land in recent years. East of Ghab is a part of the undulating Syrian desert. Because of time limitations, we covered this vast area mainly from the car window. Nahr el Kandil and Nahr Aarab, Nahr el Kebir (Ph. 11). Nahr el Kich, Nahr el Snoubar, Nahr Hraissoun, Nahr el Qaqi, Nahr Banias, Nahr el Qass, and the western and eastern walls of Ghab were surveyed. No promising site was discovered, but in view of the condition of the Lebanon coast, and report of VAN LIERE (1964) on Nahr el Kebir, there is a great possibility that this area will yield prehistoric sites if more detailed investigations are conducted.

(e) Other Areas

We had intended to investigate Jebel ed Drouz, where Palaeolithic sites have not yet been discovered. However, we found out that this mountain was an area where cave formation was extremely poor due to the numerous basalt eruptions between the Pleistocene and Holocene. So we conducted only surface collection near Taibe, between Deraa and Bosra. Jebel ed Drouz is as high as 1,800 m, but the valley development is poor because of the basalt flow. As shown in the projected profiles of Fig. 11, it possesses a knick point at 1,000 to 1,100 m. But the slope below it dips gently toward the mountains at the border of Jordan, consisting of Eocene limestone, marl and clay. We surveyed only the western slope of the mountains near Bosra-Soueida-Chahba and hardly any cave sites were discovered.

|