Abstract. Guizhou Province, China, and Japan share essentially the same families and genera of pterido-phytes, with the largest families being the same in the two regions. Japan has more tropical -and temperate genera than Guizhou, probably reflecting its moderating maritime climate in the south and the archipelago's greater latitudinal range. Guizhou's pteridophyte flora reflects its continental location and seasonally alternating wet/dry climate. Nevertheless, 288 species, about 40% of the ferns in Guizhou, are also in Japan. In Dn'opteris, 23 species, 47 percent of the total in Guizhou, are common to the two regions, but only 23 percent, or 10 species, of Polvslichum are shared between Guizhou and Japan. The differences in distribution of these two genera are thought to be based on ecological preferences of the species; the species of Dryopteris being acidophiles or calciphiles, while the species o! Potystic/wmare mostly caiciphiles.

Key words. China, Japan. Guizhou, pteridophytes, biogeography.

It is well known that eastern Asia is one of the richest areas in the world for pteridophytes, Japan, at the eastern end of the region, has a well known pteridophyte flora with 632 species of ferns and fern allies (Iwatsuki, 1992). In the Himalayan region, Chinese, Japanese, and Indian botanists have not only studied the material accumulated by British scholars, but have undertaken much fieldwork during recent decades, and have published various reports, enumerations, and books on pteridophytes. Indications are that the Himalayan region supports an equal or greater number of species.

In China, Guizhou Province occupies a central position between Japan and the Himalayan region. Although Guizhou has received relatively little attention from both western and Chinese botanists (Boufford, 1990), a nine volume flora treating the seed plants of Guizhou was initiated in 1979 and is now nearly complete. With the support of the Guizhou Academy of Sciences a project to study the fern flora of Guizhou is now being undertaken. A province-wide survey focusing especially on the pteridophytes is underway. Over half of the 80 xian (counties) and cities of Guizhou, including remote and hinterland areas, have been fully surveyed, and 5,000 numbers of fern specimens have been gathered since 1987. Together with older specimens collected by French missionaries in central, south and southwestern Guizhou and by the Chinese botanists Y. Tsiang (Jiang), H. Y. Hou, and others in many pans of the province, the fern composition of Guizhou is fairly well understood (Wang & Wang, 1989; Wang, 1992). Over 710 species in 152 genera and 53 families are known at present from Guizhou, making it possible to compare the fern flora of Guizhou with the fern floras of other parts of eastern Asia. This paper compares the pteridophyte floras of Guizhou and Japan.

Pteridophyte families in Guizhou and Japan

According to Ching's system (1978) there are 58 families of pteridophytes in Japan and 53 in Guizhou. Most families are the same but the Helminthostachyaceae, Marattiaceae, Schizaeaceae, Parkeriaceae, Acrostichaceae, and Lomariopsidaceae, represented by 1 or 2 species in Japan, are not found in Guizhou, all six families, except the Parkeriaceae, are tropical and have their distribution south of Yakushima, which lies just south of the main island of Kyushu- The pantropical Oleandraceae and the Sino-Hirnalayan mono

typic Gymnogrammitidaceae, are not in Japan. Only one species, Oleandra intermedia Ching, in the Oleandraceae is in Guizhou. The important larger families, however, including the Dryopteridaceae, Athyriaceae, Polypodiaceae. Thelypieridaceae. and Aspleniaceae, are entirely the same in the two regions.

On the basis of Iwatsuki's (1992) treatment, Guizhou has 33 families of pteridophytes; Japan has the same families plus the Schizaeaceae. It is clear that the family composition of the two areas is extremely similar, with a few additional tropical elements appearing in Japan.

Generic analysis

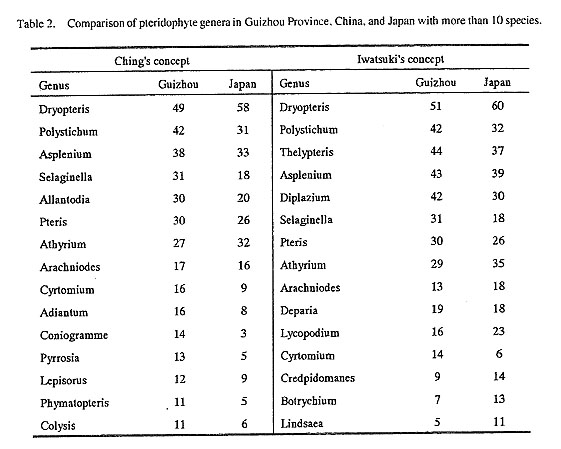

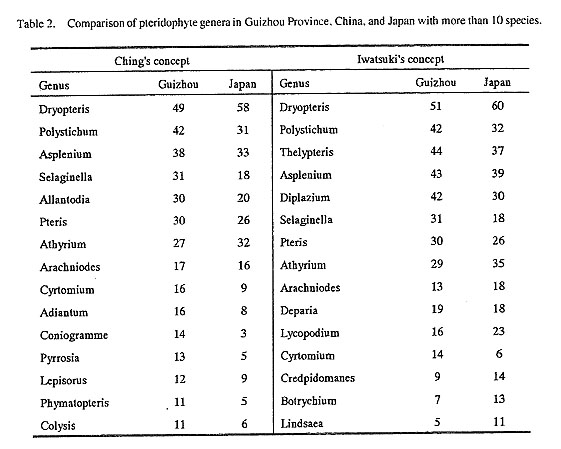

Generally, as a laxon, the genus is a relatively stable category and is regarded as important in phytogeographical analyses. In view of their different generic delimitations, Ching's (1978) and Iwatsuki's (1992) concepts are used to compare the fern floras of Guizhou and Japan.

As mentioned above, using Ching's system of classification 152 genera of pteridophytes have been rec ognized in Guizhou, and 163 in Japan. Among them 130 genera are held in common- In Iwatsuki's arrangement there are 94 genera in Guizhou and 96 in Japan, with 83 genera shared by the two regions. For convenience of comparison a list of the different genera between Guizhou and Japan is given in Table 1.

Statistics show that at least three significant observations can be made of the two regions: first, neither area has its own endemic genera; second, in comparing the larger genera, especially those comprising over 15 species, one finds that they are quite identical and constitute the main part of the flora of the two regions (Table 2); the third is that both Guizhou and Japan have many genera (about half of the total) containing only one or two species. Some genera are monotypic or oligotypic, such as Psilotum, Cheiropleuria, Drymolaenitiin, Acystopteris, etc. These points illustrate the close relationship of the fern floras of Guizhou and Japan.

From Table 1 we can see that Japan has more tropical and temperate genera than Guizhou. Ophiodenna, Sphaeropteris, Tapeinidium, Pityrogramnw, Hemlgramma, Lomar'wpsis, Arlhropteris. and Prosaptia are typical tropical elements. These genera are also distributed in the southern part of southern and southwestern China, but do not extend northward into Guizhou. Cryptogramma, Phyllitis, Botrychium and Onoclea are temperate Asian or North temperate genera distributed in northern or northeastern China, but they do not range southward into Guizhou. Another prominent fact is that there are many more filmy fern genera in Japan than in Guizhou.

On the other hand, some tropical genera, such as Bralnea, Quercifdix, Pteridrys reach southern Guizhou at the northern limit of their distribution. Guizhou has more genera of Polypodiaceae as well as more of the rather xerophytic Sinopteridaceae. Furthermore, several genera endemic to China or the Sino-Himalayan

region are also in Guizhou but not in Japan (Wu. 1987, and Table 1).

The differences are obviously the result of different geographical locations and climatic conditions. The southern islands of Japan, especially the Ryukyu Islands, which spread southward from the main islands of Japan on the western edge of the Pacific, receive abundant precipitation and experience high annual humidity and temperature. The moderating oceanic effect on the Japanese islands also prevents the extreme heat and cold experienced by a similar sized continental area. These conditions explain the greater number of more tropical and filmy fern genera in Japan. The northern part of Japan extends northwards to over 45° N, while Guizhou reaches only a little over 29° N. Perhaps altitude is also a factor. In Guizhou the highest peak is only 2,900 m above sea level. So it has fewer temperate genera than in the neighboring provinces of Yunnan and Sichuan, and Japan. Meanwhile, most of Guizhou lies within the Sino-Japanese floristic region, but the west side of the province belongs to the Sino-Himalayan region, which is influenced also by the monsoon from the Indian Ocean. The climate of western Guizhou is alternately dry and moist with annual precipitation of less than 1,000 mm in the northwestern part of the province. As a part of southwestern China, Guizhou is near the distribution center of some genera, including those of the Polypodiaceae. or at the very center of distribution of Cyrtogonellum and Phanerophlebiopsis (Wang & Wang, 1989). Hence it has different genera from Japan.

Species comparison

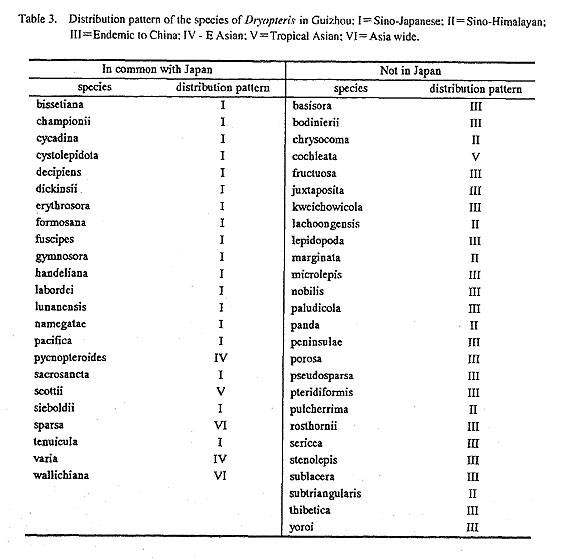

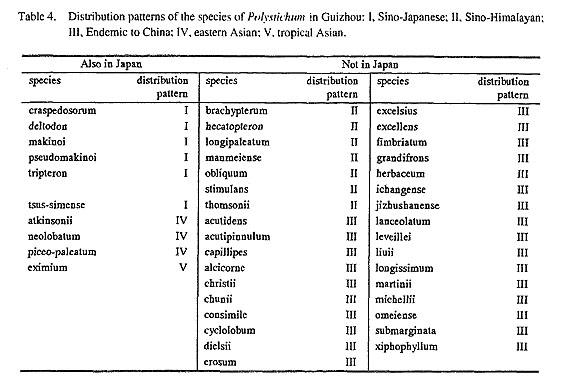

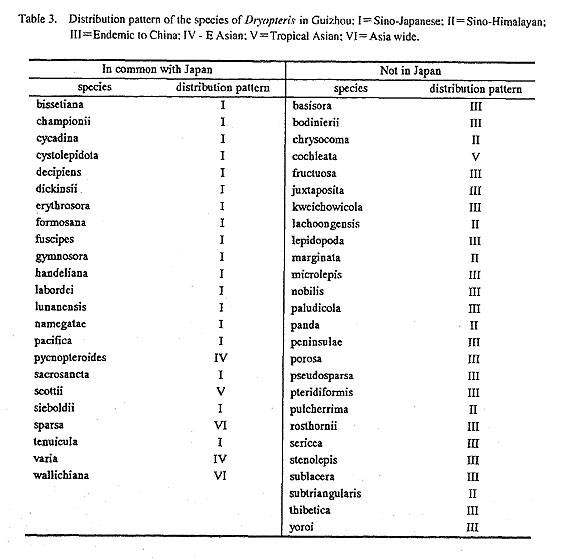

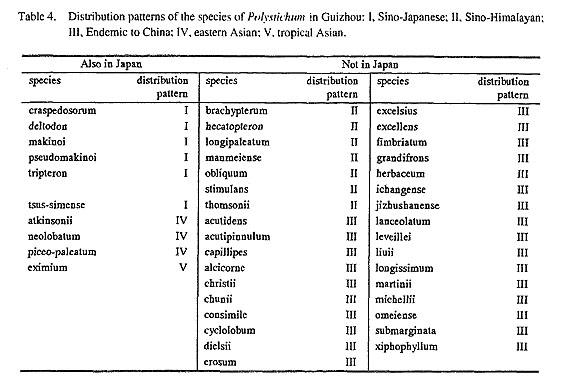

About 288 species are common to both Guizhou and Japan, accounting for 40 percent of the total number of ferns in Guizhou. H. S. Kung once suggested that the pteridophyte group stretching from the Himalaya via southwest and eastern China to Japan, characterized by Polystichum, Dryopteris, etc., be named the "Polysticho-Dryopteris Flora." Listing all the members of the two largest genera in Guizhou and comparing them with those in Japan provides some interesting information (Tables 3 & 4). In light of the present knowledge we know of 49 species of Dryopteris (excluding Dryopteris gymnophylla, D. assamensis, and D. woodsinora, which were reported in Guizhou but for which I have seen no specimens) and 43 of Polystichiim (several new species to be published have not been included) in Guizhou, and 58 and 31 respectively in Japan.

Twenty three species of Dryopteris are common to the two regions, accounting for 47% of the total species in Guizhou. Among them 18 belong to the Sino-Japanese distribution pattern, 2 are eastern Asian, and 3 are tropical Asian or Asia-wide in distribution. Nineteen of the remaining 26 species are endemic to China with only one, D. Iw'eichowicola, endemic to Guizhou. Six species occur within the Sino-Hiroalayan region and one is tropical Asian. In Japan 14 species are endemic, far more than the number of endemic species in Guizhou. Furthermore, 11 Asian or north temperate species are found at higher latitudes or in northern mountain areas of Japan and do not appear in Guizhou, and several tropical or Sino-Japanese elements also do not reach the province, although they extend westward from Japan into eastern China

Like Dryopteris, the genera Allantodia, Athyrium, Lycopodium s. l., Botrychium s. l., etc. have no, or fewer, endemic and temperate species in Guizhou than in Japan.

In Polystichum, although the situation bears a similarity with that of Dryopteris between Guizhou and Japan, some unexpected conditions appear. Ten of the Guizhou species are also in Japan, accounting for 23

percent of the total. Of the remaining 33 species 26 are endemic to China and 7 are Sino-Himalayan. In fact all of them. excluding P. acutipinnuliw, are limited to southwesi China and at least 7 of them either occur only in Guizhou (P. chnslii, P. leveillei, and P. michellii) or are chiefly distributed within the province (P. dielsii, P. fimbriatum, P. exceiiens. and P. martinii). Therefore, there are more endemic species of Polys tichum than there are of Dryopteris. Habitat is considered to be an important explanation for this phenomenon. It seems that most members of Dryopteris are acidophiles or calciphiles, but many species of Polystichum are calciphiles. Over 73 percent of Guizhou is covered by karst formations, which is ideal for calciphilous fems. including the members of Polystichum. Countless limestone caves of great variety offer particularly suitable habitats for the development of a rich fern flora. Here, sunlight is indirect or diminished, moisture is normally higher and the temperature relatively stable. Surveys show that different caves have different fern combinations and one can find Polystichum in nearly all the caves. That is why more endemic species, including some new ones to be published, are still being discovered in this sort of habitat. In Selaginella. Pteris, Adiantum, Asplenium, etc., there are also a certain number of calciphilous species which are ecologically similar to Polystichum in substrate preference.

Botanists are already aware that the term 'endemic' is used in a relative sense. With regard to Guizhou, many newly recorded pteridophytes, such as Selaginella wifldenowii, Dryopteris formosana, D. cystolepidoia, Alhyrium schimperi, Athyriopsis minamitanii, Hypodematiumfordii, found in recent years, have enlarged the range of their known distribution. On the other hand, the expanding collaborations among botanists has improved our knowledge on pteridophytes. For instance, Crypsinus yakiishimensis and Phymatop terisfukienensis appear to be conspecific and Athyrium imbricatiim and A.franguliim are considered to belong to the same species by the investigators concerned.

Guizhou is an underdeveloped province in China. Much remains to be done in the study of pteridophytes in the province. Particularly in need are systematic studies of certain complex groups and the study of in fraspeciftc variation taxonomy. The means of investigation at this point remain classical, with a need for field work to be carried out concurrently along with the help and scientific collaboration of botanists both at home and abroad.

References

- Boufford, D. E. 1990.

- The Onagraceae of Guizhou. China. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 31: 321-342.

- ———, J. H, Tsi and P. S, Wang. 1990.

- Additions to the Bora of China. J. Arnold Arbor. 71: 119-127, Ching, R. C. 1938.

- A revision of the Chinese and Sikkim-Himalayan Dryopteris with reference to some species from neighbouring regions. Bull. Fan Mem. Inst. Biol. 8: 157-268.

- ———, editor. 1959.

- Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae. vol. 2. Science Press, Beijing.

- ———. 1978.

- The Chinese fern families and genera: systematic arrangement and historical origin. Acta Phytotax. Sin. 16(3): 1-9; 16(4): 16-37.

- ——— and S, K. Wu, 1983.

- Bora Xizangica 1: Pteridophyta, 1-355. Science Press, Beijing.

- ——— and K. H. Shing. 1990.

- nora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae vol. 3(1). Science Press, Beijing. Christ, H. 1902. Filices Bodinieriancae. Bull. Acad. Int. Geogr. Bot. 11: 189-274.

- ———, 1904-1910.

- Filices Cavalerianae 1-IV. Bull. Acad. Inl. Geogr. Bot. 13: 105-120; 16: 233-246; 19: 169-178; 20:137-143.

- ———.

- Filices Chinenses. Bull. Acad. Int. Geogr. Bot. 17; 140-151.

- ———. 1910.

- Filices Micheljanae. Bull. Acad. Int. Geogr. Bot. 20: 12-16.

- Christensen, C. 1913.

- Filices Esquirolianae. Bull. Acad. Int. Geogr. Bot. 20: 12-16.

- ——— and R. C. Ching. 1934.

- Pteridrys, a new fern genus from tropical Asia. Bull. Fan Mem Inst. Biol. 5: 125-148, pl. 11-20.

- Fraser-Jenkins, C. R. 1986.

- A classification of the genus Drfopum. Bull. Brit. Mus. Nat. Hist. 14: 183-218.

- ——— and S. P. Khullar. 1985.

- The nomenclature of some confused Himalayan species of Polystichum Roth. Indian Fern J. 2: 1-16.

- Iwatsuki, K. 1975.

- Pteridophyta. In H. Ohashi, ed., Fliira of Eastern Himalaya Third Report. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo.

- ———. 1992.

- Ferns and Fern Allies of Japan. Heibonsha Publ., Tokyo.

- Kung, H. S. 1984.

- The phytogeographical features of pteridophytes of Sichuan, China with some remarks on the "Polvsticho-Dryopteris Flora." Acts Bot. Yunnan 6: 27-38.

- ———. 1988.

- Flora Sichuanica vol. 6 (Pteridophyta). Sichuan Science and Technology Press, Chengdu.

- Lu, S. G. 1989.

- Preliminary study on floristic composition and floristic features of Dryopteris from Yunnan, China. In K. H. Shing & K. U. Kramer, editors. Proceedings of the ISSP (1988). 177-179. China Science and Technology Press, Beijing.

- Shing, K. H. 1965.

- A taxonomical study of the genus Cyrtomiwn Presl. Acta Phytotax. Sin. Addit. 1: 1-48.

- Wang, P. S. 1987.

- New ferns from Guizhou. Acta Bot. Yunnan. 9: 397-400.

- ———. 1990.

- Notes on the species of Selaginella from Guizhou, China. J. Arnold Arhor. 71: 265-270.

- ———. 1992.

- Pteridophyte resources and their protection in Guizhou, China. Guizhou Sci. 10: 74-82.

- ——— and X. Y. Wang. 1991.

- Studies on Pteridophytes of Guizhou I. Guizhou Sci. 9: 227-231.

- Wang, X. Y. and P. S. Wang. 1989.

- Pteridophytes in Guizhou, China. In K. H. Shing and K. U. Kramer, editors, Proceedings of the ISSP (1988). 217-220.

- Wu, S. K. 1987.

- The phytogeographical affinities of pteridophytes between China and Japan. Ada Bot. Yunnan 9: 167-179.

- Zhang, X. C. 1991.

- Studies on the genus Athyrium sect. Strigoathyrium Ching et Y. T. Hsieh from China. Bull. Bot. Res.11(3): 1-15.