The Fansipan Flora in Relation to the Sino-Japanese Floristic Region

Nguyen Nghia Thin

Department of Botany and Herbarium, University of Hanoi, 90 Nguyen Trai Road, Dong Da, Hanoi 10.000, Vietnam

|

Abstract. Fansipan, the highest mountain in Vietnam, is situated near the southern part of the Sino-Japanese Floristic region and runs in a northwest-southeast direction. It is connected through the mountain chains in Yunnan with the Himalayan chain to the northwest. Its flora is influenced by this connection and is especially reminiscent of the Himalayan-Yunnan flora. The Pansipan flora is very profuse and diverse with over 1,659 species belonging to 723 genera and 228 families. It is characterized by a high number of relic and endemic species for the Vietnamese flora and by its archaic and original features. This paper also reports a relationship of the region's flora to the Sino-Japanese floristic region. Key words. Fansipan flora, Vietnam, Sino-Japanese Fioristic Region, Sino-Himalayan flora. Fansipan is the highest mountain in Vietnam with an elevation of 3,140 m. It is situated in the northwestern part of Vietnam and is bounded by the geographical coordinates 22°35' and 22°45'N latitude and 103° 60'E and 103°80'E longitude. Fansipan lies along the Hoang Lien Son chain, a prolongation of the Himalayan chain that extends through Yunnan, China. The mountain is derived from rocks of gneiss and ancient granites. The climate is humid or perhumid and quite cold in winter. The average annual rainfall can reach 2,732-2,778 mm. Because of the climatic similarities and the continuity of the chains of mountains from the Himalayan region to Hoang Lien Son, plants have been able to migrate easily between the Himalayan region and Fansipan. Since the Archeozoic era the Hoang Lien Son chain in general and Fansipan Mountain in particular has emerged. Because of the large number of monotypic and primitive families Takhtajan (1966) has considered this region to lie in the hypothetical cradle of the angiosperms. If the area is not the cradle of the angiosperms, however, then it is certainly a center for the congregation of many primitive forms. Based on the above noted factors, we have come to realize that Fansipan occupies a special geographical and philosophical position. Its flora has great value not only intrinsically, but also for the role it might play in the formulation of theories on the origin and evolution of the angiosperms and the patterns of plant migrations and distributions. Unfortunately, the original flora of Fansipan has been seriously destroyed and replaced by secondary vegetation and by alien plants. Research on the flora and vegetation of Fansipan Mountain is an urgent priority, as is establishing this region as an important natural reserve in Vietnam, and our research is aimed at providing the background information to justify that status.

|

|

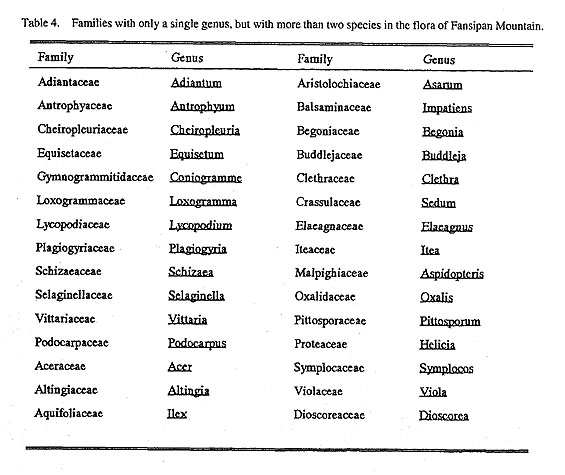

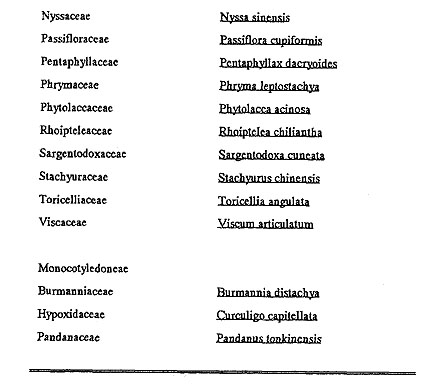

Of the above families there are 8 monotypic families on Fansipan: Berberidaceae, Bretschneideraceae, Dipsacaceae, Pentaphyllaceae, Rhoipteleaceae, Sargentodoxaceae, Slachyuraceae and Toricelliaceae.

The Fansipan flora also contains a number of endemic taxa that occur nowhere else, and a high percentage of endemics that are more widespread throughout northern Vietnam. For example, the Orchidaceae have 19 endemic species in northern Vietnam and 18 of them occur on Fansipan; Carex (Cyperaceae) has seven endemic species in northern Vietnam, and six of them occur on Fansipan. According to Chi (1975), 25 genera and 39 species were discovered originally from Fansipan.

3) Diversity of the vegetation

Fansipan is a high mountain situated at the northern margin of the tropical mainland of Southeast Asia and controlled by a monsoon climate. The region is climatically at the limit for tropical rainforests, which are more or less replaced by subtropical and temperate forests or, more exactly, by montane rainforests to the north.

Based on ecology, structural characters and plant components, the Fansipan vegetation can be divided into several main belts and types as follows.

1. Tropical vegetation belt

The tropical vegetation belt is found only below 700 m, and mainly on the east side and in deep valleys. This belt includes typically tropical vegetation. Formerly, it was covered by tropical monsoon forests with the dominant species belonging to families such as Fagaceae, Leguminosae, Sapindaceae, Burseraceae, Me-liaceae, Magnoliaceae, Lauraceae and Anacardiaceae. The original forests were destroyed by shifting cultivation, over-exploitation and by forest fires and have been replaced by secondary forests in valleys and along rivers, by savannas on the slopes, or by cassava, rice or maize fields. Since Fansipan is at the altitudi-nal and latitudinal limits of tropical forests, the flora of the rain forest is at the northern margin of the tropical zone and is transitional to subtropical forests like those in southern China.

1.1. Secondary forests. Secondary forests are distributed in valleys and along rivers and are derived from the former primitive forests. The plant components are mainly species of typical tropical rainforests, but their size and structure are changed through the impact of people and the influence of environmental factors. Since the basic components are intact, the original forests might redevelop if these seeondary forests could be protected, because humidity and the fertility of the soil are still secure.

1.2. Savannas. Savannas develop after long periods of shifting cultivation on heavily eroded sites where the water has been lost. Woody plants are unable to grow on such soils, but are replaced by grasses. Savannas are found on steep slopes and in open places. The vegetation of these sites is characterized by Miscan-thus floribundus and Saccharum arundinaceum with some pioneering weedy trees as Liquidambar formo-sana, Mallotus apelto, M. paniculatus, Macaranga denticulata, Trema orientalis and Musa spp. in wet places and Imperata cylindrica, Arundinella spp., Cratoxylon fomosum, Rhodomyrtus tomentosa and Melastoma candidum in dry places.

2. Subtropical vegetation belt

The subtropical vegetation belt is transitional between the monsoon rainforests, montane temperate forests and the montane evergreen broadleaved forests on tropical mountains. The subtropical belt is usually located at elevations between 1,000 and 2,000 m. It is differentiated at sight from tropical rain forests by the shorter stature of the forest trees, the continuous, even crowns of the upper layer (without emergent trees), a lack of buttresses and cauliflory and the absence of woody lianas. Caudate leaves are less frequent while epiphytes are more abundant. In addition, the family Cyatheaceae is frequent in these forests as a characteristic plant. The average temperature in this belt ranges from 15°C to 20°C, with a minimum of 15°C. These forests provide favorable conditions for many species of the Tertiary flora which are characteristic in northern Vietnam and southern China and for many species with Himalayan affinities. Some typically tropical plants, such as Gnetum montanum, are also found within this belt, and even to as high as 2,200 m. Unfortunately, many places within the subtropical bell have now been completely changed and have been replaced by different vegetation types. The vegetation within this zone can be divided into the following three main types.

2.1. Subtropical dense forest. This was formerly a common forest type. It is characterized by such Tertiary plant families as Lauraceae, Magnoliaceae, Theaceae, Sapotaceae, Hamamelidaceae, Betulaceae and Fagaceae. These families are not only abundant and diverse in numbers of taxa, but also in number of individuals within the area, where they form magnoliaceous-lauraceous forests, fagaceous forests, etc. These forests are now present in deep valleys and on steep slopes at places such as Ban Khoang and Cong Troi.

2.2. Subtropical savannas. This common type of vegetation has resulted in response to the destruction and over-exploitation of subtropical forests, forest fires and shifting cultivation. The vegetation here includes species of Miscanthus floribmdus, Arundinella nepalensis, Imperata cylindrica, Microstegium sp. and many herbaceous or short-lived shrubby species such as Buddleja spp., Viburnum cylindricum, Luculia intermedia, Rubus ellipticus, Osbeckia crwita, Oxyspora paniculata, Porana racemosa, Polygonum panicu-latum, P. chinense var. scabrum. Litsea cubeha. Clematis leschenaultiana and some trees such as Alms nepalensis, Saurauja nepauiensis, Platycarya kwangtungensis, Acer campbellii, Wrighlia speciosissima and Itoa orientalis on non-limestone soils.

Some tree species such as Aesculus, Beilschmiedia sp., Quercus spp., Acer campbellii, Wrightia speciosissima, Michelia martini, Amentotaxus yunnanensis, Itoa orientalls, Schefflera sp., Hex spp. and Ficus hookeri grow on limestone in deep soils, and some woody plants, such as Eurya sp., Hydrangea aspera, Ligustrum sinense, Viburnum cylindricum, Berberis wallichii. Phyllanthus sp., Lilsea cubeba, Dalbergia collettii. Clematis fasciculiflora, Carpinus pubescens and Platycarya kwangtungensis, grow on limestone soils with many large stones protruding from the surface.

2.3. Montane grassland. Montane grasslands develop after a long period of shifting cultivation, trampling by domesticated buffaloes, and forest fires followed by soil erosion and water runoff. The cover at these sites is made up mostly of graminoides and forbes belonging to Poaceae, Cyperaceae and Fabaceae, but also with some Asteraceae and Liliaceae, and some species of Melastoma, Osbeckia, Rubus and Pteridium.

3. Temperate vegetation belt

The temperate vegetation belt is commonly found at altitudes above 2.000 m and is characterized by temperate species, most of which have a strong affinity with the Sino-Japanese floristic region. The components belong to such genera as Abies, Acer, Adinandra, Aesculus, Agapetes, Allomorphia, Alnus, Altingia, Coptis, Cornus, Crawfurdia, Embelia, Enkiauthus, Fagus. Fokienia, Hydrangea, Huodendron, Lirioden-dron. Magnolia, Primula, Quercus, Rhederodendron, Rhoiptlelea, Rhododendron, Sorbus, Ternstroemia, Vaccinium and Valeriana.

3.1. Temperate forests. Temperate forests are found in deep valleys and on steep slopes and include species of the above noted genera. These types of forests are relatively common at high altitudes and are domi nated by species belonging to Aceraceae, Hippocastanaceae. Fagaceae, Magnoliaceae, Lauraceae, Cupres-saceae. Pinaceae. Taxaceae and Theaceae.

Within the temperate belt natural conditions are completely different from those in tropical rain forests. Characteristic features are heavy rainfall. a lower rate of evaporation. low temperatures and strong winds, which restrict plant growth. Most of the trees are very short. Trees lack the straight, unbranched trunks they exhibit in the lowlands and instead become gnarled, twisted and often multi-stemmed, and even the leaves are much smaller, narrower and more leathery. The branches, trunks, and even the forest floor, are covered by mosses and lichens. Ferns and other epiphytes, including orchids. rhododendrons, Araceae and Arali-aceae are quite common in these forests. Many cold tolerant groups, such as species of Ericaceae and some species of Abietaceae, Podocarpaceae and Pinaceae, and other groups adapted to soils poor in nutrients occur on the mountain tops.

3.2. Montane cold savannas. Montane cold savannas usually occur on the ridges and on steep slopes, which were formerly occupied by forests. These communities have formed where shifting cultivation and fires have destroyed the original forests. Within these savanna communities most of the plants are herbs and shrubs belonging to the Poaceae, Cyperaceae. Liliaceae, Hypoxidaceae, Zingiberaceae, Gentianaceae, Ericaceae, Rosaceae, Melastomataceae, Lamiaceae, Hypericaceae and Gesneriaceae and to many pteridophyte families. These plants are light-loving and cold-adapted. Most high summits of Fansipan are covered by this type of vegetation.

4. Floristic elements and relations with the Sino-Japanese Floristic Region

The Fansipan flora is very interesting and unique. Besides the endemic species of Fansipan, and the endemic species of Vietnam that occur on Fansipan (about 30% of the endemic species in the Vietnamese flora), the Fansipan flora also has representatives from three additional floristic elements: a tropical element; a subtropical element; and a temperate element.

4.1. Tropical element. As mentioned above. Fansipan lies within the tropical zone, so of course there are many representatives of tropical families. Families with tropical affinities usually reach an elevation of about 1,500 m, and some of them even reach 2,000 m. These include Cyatheaceae, Gnetaceae, Annonaceae, Clusiaceae. woody Euphorbiaceae, Hemandiaceae, Icacinaceae, Polygonaceae, Proteaceae, Araceae and Combretaceae.

Typically tropical genera, such as Actinodaphne, Aleurites, Artocarpus, Calamus, Caryota, Citrus, Duabanga and Wendlandia, play an important role in the forest. Tropical shrubs and herbs are also common under the forest canopy and include such genera as Acorus, Anotis, Balanophora, Calamus, Dichroa, Diospyros, Dioscorea, Pasania, Mallotus, Macaranga. Disporum, Sarcandra, Vernicia and Wendlandia.

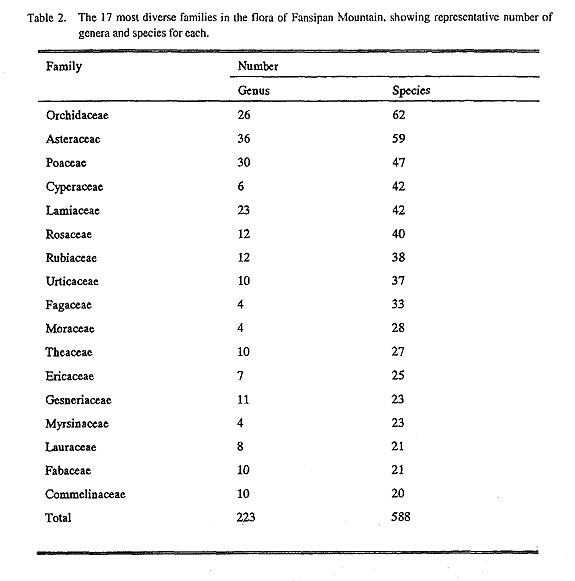

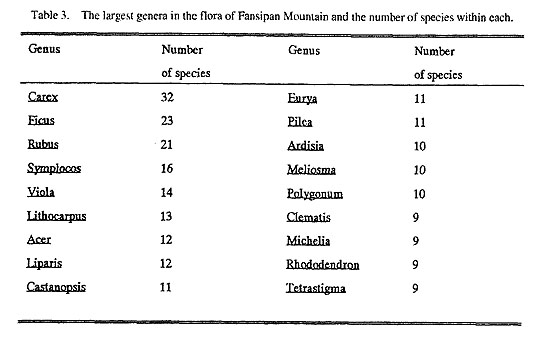

4.2. Subtropical elements or Tertiary floristic elements. An important floristic element of the Fansipan flora is the subtropical element. This is mainly the Tertiary floristic element of northern Vietnam and southern China, which contains such representative families as Orchidaceae, Aceraceae, Rubiaceae, Lauraceae, Theaceae, Magnoliaceae, Gesneriaceae, Myrsinaceae, Urticaceae, Moraceae, Fagaceae and Hamamelida-ceae, and such well known genera as Acer, Carex, Ficus and Symplocos.

The Tertiary plants show the ancient character of the Fansipan flora, with the present day natural condition being nearly similar to the fossil floras of the Tertiary era on one hand and to the present day Sino-Japanese flora on the other.

The subtropical characteristics are expressed by the presence of many genera and species, including Hydranya (Hydrangeaceae), Embelia (Myrsinaceae). Polygonum capitatum, P. flaccidum, P. palmatum, P. thunbergii (Polygonaceae), Ranunculus, Anemone, Coptis (Ranunculaceae), Huodendron, Rhederodendron (Styracaceae), Crawfurdia, Gentiana (Gentianaceae), Schisandra, Kadsura (Schisandraceae), Buddleja (Baddlejaceae), Fagraea (Loganiaceae), Cornus (Comaceae), Allomorpha, Anerincleistus, Bredia, Fordio-phyton, Oxyspora, Plagiopetalum, Sarcopyramis (Melastomataceae), Viola (Violaceae), Adinandra, An-neslea, Gordonia, Pyrenaria (Theaceae), Exbucklandia, Rhodoleia, Liquidambar (Hamamelidaceae), Alei-mandra, Liriodendron, Manglietia, Magnolia (Magnoliaceae). Sorbus, Potentilla (Rosaceae), and many others.

From these examples we can see that many genera, and even many of the species, are common to the floras of northern Vietnam and southern China and also show the relationship of the Fansipan flora to the flora of the Sino-Japanese Floristic Region.

4.3. Temperate element. Because Fansipan mountain exceeds 3,000 m in elevation, many tropical and subtropical groups are gradually replaced within the 2,000 to 3,143 m range by temperate species. The temperate element is characterize by species belonging to Paris (Trilliaceae), Betula, Alnus (Betulaceae), Leu-coihoe, Enkianthus, Pieris, Rhododendron. Vaccinium (Ericaceae), Celtis, Ulmus (Ulmaceae), Fagus, Cas-tanea, deciduous Quercus (Fagaceae), Aesculus (Hippocastanaceae), Juglans, Platycarya (Juglandaceae) Crawfurdia, Gentiana, Swertia (Gentianaceae), Tsuga, Abies, Fokienia, Amentotaxus (Gymnospermae) and Lycopodium, Huperzia (Lycopodiaceae). These genera, and the species contained within them, are common in the Sino-Japanese floristic region and provide evidence for the relationship between the two floras.

Conclusion

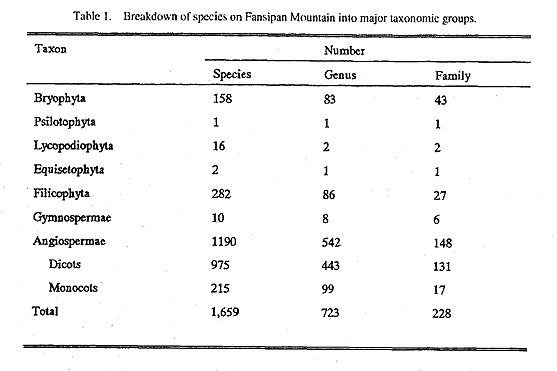

The Fansipan flora is very profuse and diverse, with 1,659 species, 723 genera and 228 families belonging to 7 divisions, of which the angiosperms, Filicophyta and Bryophyta are the most diverse and profuse and Psilotophyta and Equisetophyta are the least diverse and profuse. The abundance and diversity of bryo-phytes give evidence of the humid, cold nature of the study site.

The area contains many relic and endemic taxa, not only for Fansipan but also for Vietnam, and also not only at the species level, but also at higher levels. Takhtajan (1966) has considered Fansipan to lie within the hypothetical cradle of the angiosperms. And even if this is not the cradle, it is still one of the leading centers of polymorphism and species diversity in the world.

Since Fansipan lies next to the Sino-Japanese floristic region and is connected physiographically with the Himalayan chain, the floras of the, two regions come into contact and overlap each other. Fansipan's high floristic affinities with the Sino-Japanese region is clearly expressed in the subtropical and temperate belts, not only in the floristic components, but also in the vegetation structure, and especially in the presence of the Tertiary floristic elements, which are so characteristic of the Sino-Japanese Floristic Region.

References

- Anonymous. Forest Trees of Vietnam. Vols. 1-8. Hanoi.

- ———. 1971-1975.

- Iconographia Cormophytorum Sinicorum. Vols. 1-6. Science Press, Beijing.

- Aubreville, A., M. L. Tardieu-Blot, J. E. Vidal and P. Moral. 1960-1992.

- Flore du Cambodge, du Lao et du Vietnam. Fasc. 1-20. Paris.

- Ban, N. T. 1990.

- The Families of Angiosperm Plants in Vietnam. p. 84-95 In Selected Collection of Scientific Reports on Ecology and Biological Resources (1986-1990). Hanoi.

- ——— et al. 1984.

- List of Taynguyen Plants. Biol. Inst. Hanoi.

- Brummitt, R. K. 1992.

- Vascular Plant Families and Genera. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Chi, V. V. 1975.

- Flora and Vegetation of Sapa (Laocai Province). Hanoi.

- Chun, W. Y., C. C. Chang and F. H. Cnen, ed. 1964.

- Flora Hainanica. Vol. 1. Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing.

- Chun, W. Y. and C. C. Chang, ed. 1965.

- Flora Hainanica. Vol. 2. Chinese Academy of Sciences. Beijing.

- Guangdong Institute of Botany, ed. 1974.

- Flora Hainanica. Vol. 3. Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing.

- ———, ed. 1977.

- Flora Hainanica. Vol. 4. Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing.

- Ho, P. H. 1970.

- Flora of South Vietnam. Vol. 1. Saigon.

- ———.

- 1972. Flora of South Vietnam. Vol. 2. Saigon.

- Ke, L. K. et al.

- 1969-1976. Common Flora in Vietnam. Science and Technology Publishing House. Hanoi.

- Leeomie, H.

- 1905-1954. Flora General de l'Indo-Chine. Vols. 1-7. Paris.

- Loc. P. K. 1984.

- Species belonging to Pinopsida in the Vietnam flora. Biol. J. 6(4): 5-10.

- Pocs. T. 1965a.

- Analyse Aire-géographyque ei Écologique de la Flora du Vietnam Nord. Egri. Pedagog. Foisk. Évk.

- ———. 1965b.

- Prodrome de la Bryoflore du Vietnam. Egri. Pedagog. Foisk. Évk. 3: 453-495.

- Takhtajan, A. L. 1966.

- Systema el Phylogenie Magnoliophyiorum. Moscow-Leningrad.

- ———. 1969.

- Flowering Plants, Origin and Dispersal. Edinburgh.

- ———. 1980.

- Outline of the Classification of Flowering Plants (Magnoliophyta). Bot. Rev. 46: 225-259.

- ———. 1987.

- Sistema Magnoliofitov. Leningrad.

- Thin, N. N. 1992.

- Update List of Cucphuong Flora. Hanoi.

- Trung, T. V. 1978.

- Vegetation of Vietnam Forest. Ed. 2. Science and Technology Publication House, Hanoi.

- Wu, C. Y., ed. 1977.

- Flora Yunnanica. Vol. l. Science Press. Beijing.

- ———. 1979.

- Flora Yunnanica. Vol. 2. Science Press, Beijing.

- ———. 1983.

- Rora Yunnanica. Vol. 3. Science Press, Beijing.

- ———. 1986.

- Flora Yunnanica. Vol. 4. Science Press, Beijing.

- ———. 1992.

- Flora Yunnanica. Vol. 5. Science Press, Beijing.

- ———. 1995.

- Flora Yunnanica. Vol. 6. Science Press, Beijing.