CHAPTER 11

The Ecology of the Middle Paleolithic Occupation at Douara Cave, Syria

Takeru Akazawa

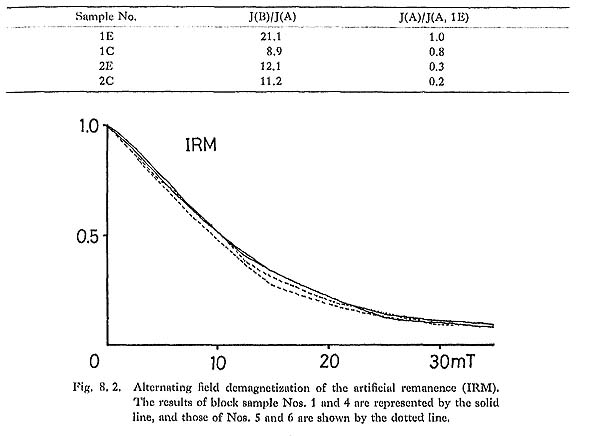

11. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe 1970, 1974, and 1980 excavations at Douara Cave revealed an impressive sequence of superimposed occupations extending from the Middle Paleolithic to the Epipaleolithic, although the Upper Paleolithic sequence is completely missing. The sequence of the Middle Paleolithic assemblages manifests significant technological differences between the two industries from the designated levels III and IV (upper and lower). Assemblage III is characterized by a dominance of the prepared core technique of typical Levallois type, while latter assemblage is unlike the typical Levallois industries and has many similarities to the blade industries characterized by prismatic core techniques, which occur early in the Levantine Middle Paleolithic sequence, e.g. from Tabun D, Abou Sif, and Hummal la. The Douara Cave is located in a transitional zone between two diverse environments: mountainous zones to the north and steppic, piedmont landscape to the south. The present conditions around the cave are completely open and very sparsely vegetated, showing the completely denuded landscape of the area. Analysis of plant remains associated with level IV, however, suggests that there may have been some forest dominated by Celtis trees, and open grass to shrub lands with Boraginaceae, within the 10-km catchment area of the Douara Cave during the Middle Paleolithic period, although the overall environmental and climatic conditions were not essentially different from the semi-arid ones prevailing today. These conditions would have provided more adequate grazing for the herbivorous animals identified from the cave and also sufficient ground water capacity to maintain the Palco-Palmyra Lake through years. 11.2 MIDDLE PALEOLITHIC ASSEMBLAGES OF THE SITEComparing the Middle Paleolithic assemblages from levels III and IV, unearthed in 1974 (Akazawa, 1979a) with those excavated in 1984 (Chapter 5 in this volume) has clarified in more detail the provisional view that there were significant technological differences between the two industries. The level III assemblage is seen to match entirely the classic type of Levallois industries in the Levantine Middle Paleolithic assemblages described so far. The most outstanding feature of the III assemblage is the dominance of the prepared core technique of typical Levallois type in the production of tool blanks, i.e., the cores designated by Copeland (1975, 1981, 1983) as centripetally-prepared Levallois type together with 'classic' Levallois tortoise type are predominant (Akazawa, 1979a: Fig. 8.2). Another significant feature is the popularity of broad oval Levallois flakes in the production of blanks. An examination of the flaking direction showed that these oval flakes have centripetal preparation on their dorsal surfaces.

In contrast, the level IV assemblage is unlike the typical Levallois industries and has many similarities to the prismatic blade core techniques referred to by Copeland (1981, 1983). The level IV assemblage is characterized by two features: one is the prismatic core technique and the other a strong tendency toward blade manufacture. The assemblage has an exceedingly high blade index amounting to 70 percent of the total blanks, a trait unusual in the common Levantine Middle Paleolithic context. Of these blades, the uni- and bi-directionally opposed flake-scarred ones are dominant. These blades were predominantly detached with a soft hammer (personal communication from Ohnuma, 1986). This evidence indicates that these blades were derived from cores with single-and opposed-platforms which are also dominant in the IV assemblage. That is to say, the core technique and blank production processes are wholly compatible in the IV assemblage. No evidence of the cresting technique, one of the techniques used to prepare ridges on. the flaking face of a core, nor any trace of Levallois side-preparation can be seen in the level IV collection. 11. 2. 1 Levantine Middle Paleolithic industriesVarious studies of the Levantine Middle Paleolithic industries (e.g. Copeland, 1975; Jelinek, 1982; Ronen, 1979; Skinner, 1965) have proposed, with some differences in the analytical data, that the Levantine Mousterian can be classified into an earlier and a later phase. The earlier phase, which is usually described under the nomenclature of Phase 1, Tabun D, or Abou Sif type, has been primarily defined by the depositional contexts of Tabun D and Abou Sif and their associated lithic assemblages. Their characteristics could indicate the following techno-typological features (Jelinek, 1982): numerous Levallois points, frequently elongated; high proportion of blades, frequently with plain platforms; high proportion of Upper Paleolithic type tools; and low frequencies of centripetally-prepared, broad Levallois flakes. The later phase is grouped under the nomenclature of Phase 2/Phase 2-3 or Tabun C/ Tabun C-B type. The defining characteristics of this variant as described by Jelinek (1982) are: numerous broad Levallois flakes frequently produced from centripetally-prepared cores; broad, short Levallois points, sometimes very few in number; relatively few blades; and high frequencies of side-scrapers among the retouched tools. Recently, a particularly relevant example of the Levantine Middle Paleolithic assemblages has been described-the Hummalian industry which is based upon the collection from level Ia at Hummal, El-Kowm, approximately 80 km NNE of the Douara Cave. At this type station, the Hummalian is found above the Acheuleo-Yabrudian in level Ib and below a series of Phase 1 Mousterian assemblages in level II. The defining characteristics of this industry, as recently described by Hours (1982), Bergman and Ohnuma (1983), and Copeland (1985), are as follows. The industry is technologically characterized by blade manufacture with a high blade index of 81.6 (Besancon et al., 1981; Copeland, 1982; Hours, 1982) to 52.6 (Copeland, 1985: 178). The majority of the blades are characterized by having uni-directional or bi-directional opposed dorsal scars, and centripetal preparation, which is often characteristic of Levallois flaking, is entirely absent in the collection which Bergman and Ohnuma (1983) studied. According to them, the blades were predominantly detached from prismatic cores with single- and opposed-platforms by a hard hammer, and cresting was utilized as one of the techniques for core preparation, as evidenced by the associated crested blades. In addition, evidence of Levallois side-preparation is very low in frequency (Copeland, 1985: 178). Bergman and Ohnuma (1983: 178) concluded, that "the blades we studied from Hummal Ia are probably best described as non-Levallois for the time being". Typologically, the Hummalian is very rich in retouched tools-various kinds of side scrapers, and backed knives, and Mousterian and Hummalian points, which are mostly made on blades (Copeland, 1985). As a result of these studies we now have a better understanding of the industrial sequence from the Late (Upper) Acheulian to the Mousterian in the Levant: Late (Upper) Acheulian, Acheuleo-Yabrudian or Yabrudian of Acheulian facies, Hummalian, Phase 1 (Abou Sif or Tabun D type) Mousterian, and Phase 2/Phase 2-3 (Tabun C/Tabun C-B type) Mousterian. 11.2.2 Chronological position of the Douara assemblagesIn comparing the Douara Middle Paleolithic assemblages summarized earlier with the scheme described above, the Douara III assemblage seems to match the Phase 2/Phase 2-3 Mousterian. For example, technologically the level III assemblage closely resembles Phase 2/Phase 2-3 Mouaterian, where each has a high frequency of broad Levallois flakes derived from centripetally-prepared cores defined by Copeland (1975: 330) as 'classic' Levallois tortoise cores. The Douara IV assemblage, on the other hand, does not seem to fit completely into any of these models. Nevertheless, it certainly has some resemblances to Phase 1 Mousterian and Hummalian from a technological viewpoint; each being characterized by a high frequency of blades detached from prismatic blade cores and exhibiting no sign of Acheulian and Yabrudian facies. According to Copeland's (1985) recent work, the Middle Paleolithic blade-like industries have been typified by the assemblages from Hummal Ia, Abou Sif, Tabun D, Bezez B, and Hazer Merd C, and also from Larikba (Vandermeersch 1966), Rosh Ein Mor (Crew, 1976), and Nahal Aqev (Munday, 1977). Although the basic inventories of these assemblages occur in widely varying ratios, both technologically and typologically, there are remarkable similarities in their pronounced laminar aspect. Taking that fact into account, I conclude that the Douara IV assemblage may add one new example to the suite of blade industries occurring early in the Middle Paleolithic sequence of West Asia. However, the Douara IV assemblage is clearly typologically distinct from these blade industries in its extremely low frequency of retouched tools. For instance, the elongated Mousterian points (including Hummalian points as designated by Copeland, 1985) and backed knives on blades, that character the Hummalian and Abou Sif assemblages which otherwise desclose strong technological similarities to Douara IV, are completely lacking at Douara Cave. That is to say, the Douara IV assemblage may have fitted somewhere in the earlier phase of the Levantine Middle Paleolithic so far as technology is concerned. In addition to this, the Douara IV collection lacks the cresting technique and blade detachment with a hard hammer which are characteristic of the Hummalian industry. Given these considerations, I suggest that the level IV assemblage should be further studied as to whether it is a chronological or a local variation (or both) within the Levantine Middle Paleolithic context. 11.3 ECOLOGY OF HUMAN OCCUPATION AT DOUARA CAVEAccording to Harrison's (1964) work, West Asia falls into two major zoogeographical zones: Boreal Eurasiatic and Saharo-Sindian types (see Payne, 1983: Fig. 15.6). The Boreal Eurasiatic zone, which is characterized by a faunal assemblage adapted to rather colder, wetter boreal conditions, covers the Levantine coastal regions and Anatolian plateau. The Saharo-Sindian zone, associated with a faunal assemblage adapted to arid conditions, covers desert and steppe zones of the Arabian peninsula. Paleolithic cave sites that have been excavated in West Asia are mostly situated in the first zone, and their faunal assemblages, when identified in detail (e.g. Amud in Israel: Takai, 1970; Ksar Akil in Lebanon: Hooijer, 1961; Tabun and Wad in Israel: Bate, 1937) are dominated by Boreal Eurasiatic species. Douara Cave lies within the Saharo-Sindian zone, and its faunal assemblage can be expected to contribute to our currently poor knowledge of the Saharo-Sindian fauna during the Pleistocene. Moreover, we would expect the Douara animal bones to be one source of evidence with which to discuss environmental conditions in the Palmyra Basin during the human occupation at Douara. More specifically, we need the additional data required for any further consideration of the Paleo-Palmyra Lake, the existence of which was discussed by Sakaguchi, a physical geographer of our 1974 Expedition. Sakaguchi (1978a, b; see also Chapter 1 in this volume) concluded that Paleo-Palmyra Lake existed at some time in the past, as evidenced by a series of lacustrine terraces and other evidence of lacustrine deposits around the Sabkhet Mouh. He concluded that "the Middle Palaeolithic age in this region was rainy and cool in the summer, and in the winter colder than today" (Sakaguchi, 1978b: 110). If Sakaguchi's hypothesis is correct, we would expect to find more Boreal Eurasiatic species among the Douara faunal assemblages than are found in the area today, since the Douara Cave lies close to the zoogeographic boundary between Boreal Eurasiatic and Saharo-Sindian zones, as referred to by Payne (1983: 10). 11.3.1 Mammal remainsSebastian Payne (1983) studied all the samples of mammalian bones collected in the 1974 excavations and documented a collection representing 29 mammalian species and genera (see Payne, 1983: Table 15. 15). Based upon the assemblage identified, the Douara fauna is dominated by the Saharo-Sindian species. That is to say, the Boreal Eurasiatic species such as Dama, Cervus, Capreolus, Sus, Hippopotamus, Bos, and Rhinoceros, and, among smaller mammals, Microtus, Apodemus, Mus, and Erinaceus, which are common in the Pleistocene deposits at Tabun, Wad, and Ksar Akil sites distributed in the Levantine coastal region, are all completely lacking at Douara. In contrast, the Douara material is dominated by steppe and desert genera such as Camelus, Gazella, Hemiechinus, Psammomys, Meriones, Gerbilhis, and Allactaga, which form the major part of the Saharo-Sindian species. Of these mammals, the rodent genera such as Meriones, Psammomys, Allactaga, and Jaculus are a more direct source of evidence to think about environmental conditions around the cave. These smaller mammals, which were brought to the cave by owls living nearby, suggest that environmental conditions around the cave might have been characterized by low rainfall and summer drought as is the case today (Payne, 1983: 103). Payne (1983: 93) concluded that "the close similarity between the Douara fauna and the present-day fauna in the Palmyra area is striking, and suggests that this fauna is long established and long adapted to the semi-arid conditions of this area. Fossil records and modern distributions suggest that the Near Eastern semi-arid zone must on occasion have contracted or shifted substantially, allowing, for instance, Microtus to reach Libya; but the close similarity of the Douara Cave fauna to the present-day fauna of this zone suggests that the Near Eastern semi-arid zone never disappeared completely during the Upper Pleistocene". Under these circumstances, environmental conditions in the Palmyra Basin during the Middle Paleolithic occupations were not essentially different from the semi-desert conditions prevailing today, and the faunal association today of such areas was already in existence then with a few exceptions. Thus, the Middle Paleolithic occupations seem to have occurred in dry environmental conditions from the beginning. Another source of evidence about past environmental conditions in the Palmyra Basin which ought also to be concerned lies in plant remains. 11.3.2 Plant remainsA number of soil samples from the Douara Cave and other locations (including the Sabkhet Mouh) were submitted for palynological study (Sohma and Sasaki, 1973). Pollen grains associated with the Middle Paleolithic occupations at Douara Cave were extremely few in number: 1 Pinus, 2 Juniperus, 1 Artemisia, 7 Chenopodiaceae, 1 Gramineae, 1 Pistacia, and 4 unidentifiable. These scanty pollen samples, in addition to the possibility of long-distance transportation by wind, cannot be used to describe environmental conditions around the cave with any certainty. Matsutani (1979) detected quite a lot of amorphous silica fragments in the Middle Paleolithic deposits, especially from level IVB in 1974 excavations. In microscopic structure these resembled spodograms of the seeds of some Boraginaceae, but Matsutani's work cannot yet refer these fragments to genus and many species of Boraginaceae now grow in West Asia in a wide range of ecological conditions (Davies, 1978). But while Boraginaceae remains may reveal little about paleo-environmental conditions in the Palmyra area, it might be possible to suggest that around the cave an open, grass to shrub land associated with some Boraginaceae developed. Although the scanty plant remains from the Douara Cave can be explained by the drier conditions referred to by Payne (1983: 94-95), other possibilities should be considered. Plant remains tend to be underrepresented in archaeological contexts, because plants may be easily destroyed in a variety of ways and can be decomposed into elements too small to identify. Further bias may be caused by the loss of smaller samples during excavations (Payne, 1972). On closer examination of the excavated earth from 1984, we found that evidence of plant remains from the 1970 and 1974 seasons might have been seriously biased by our sampling methods. That is to say, during the 1984 excavation, and after processing soil samples taken from the cave deposits, it was found that large amount of plant remains were contained in levels IVB to IVD (see also Chapter 4 in this volume).

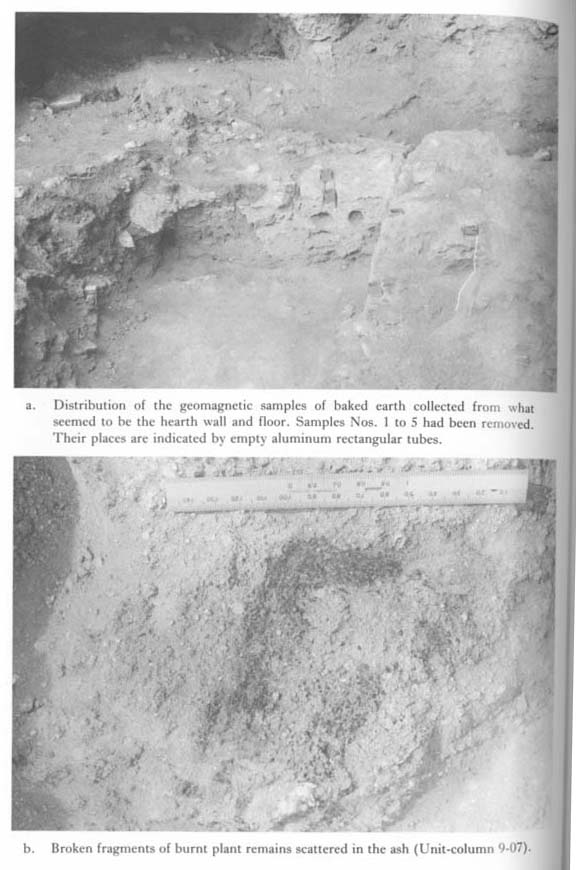

The first appearance of these plant remains was a rather fortuitous occurrence during excavation. A concentration of carbonized plant remains was found in situ in level IVB. It consisted of hundreds of fragments within an area of about 15 cm in diameter (see Plate 3. 2: b in this volume). On closer examination of the vertical section of the deposit, a number of complete and mostly complete grains were found scattered in levels IVB to IVD. Thus, a large amount of plant remains was collected using two different methods: one was to collect the well-preserved, complete specimens from throughout the excavated area, and the other was to collect every specimen from soil samples which were systematically taken from the deposits IVB to IVD.

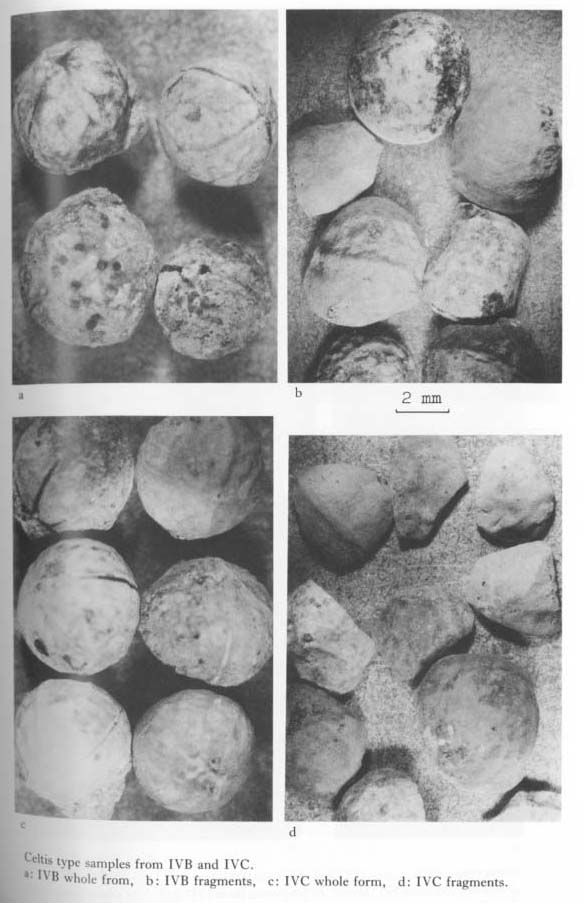

Although identification of the plant remains is still underway by Gordon Hillman, London University, the results of a preliminary examination have been published by Matsutani (see Chapter 7 in this volume). Her work is based upon the following two different procedures: identification on the basis of gross morphological criteria which is mainly applied to well-preserved remains; and the use of cell structures as taxonomic criteria under the scanning electron microscope. Although Matsutani's study is also under way, her preliminary results, in addition to a preliminary personal communication from Gordon Hillman in 1985, are summarized below. Carbonized plant remains are dominated by fragmentary endocarps of Celtis and Boraginaceae nutlets, the majority of which are identifiable as Celtis (see Table 7. 1 and Plates 7. 1-18 in this volume). The Celtis endocarps are further classified into the two species C. australis and C. tournefortii based upon such diagnostic features as the tissue and cell structures of the endocarps, and the thickness of their stony layers. But Boraginaceae nutlets cannot yet be referred to species, or even to genus.

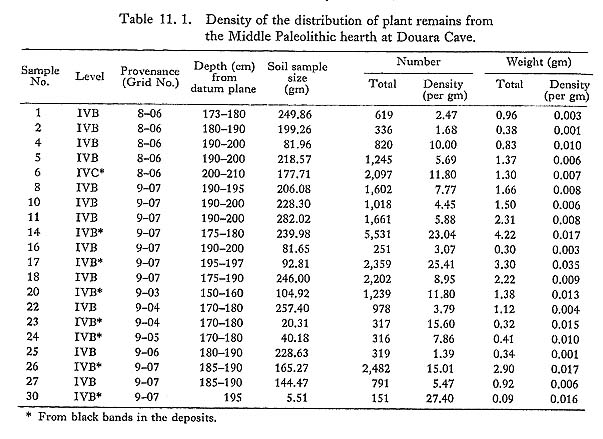

In order to estimate the quantity of these remains, we compared the results of 20 soil samples processed by a 1 mm dry-sieving method in the laboratory (Table 11. 1). The results indicated two broad groups. One group is composed of nine samples (Nos. 4, 6, 14, 17, 20, 23, 24, 26, 30), in each of which there are either, or both, more than 10 pieces or a combined weight of more than 0.01 gm per gram of deposit. The remaining samples are characterized by a much lower density of remains, as can be seen in Table 11. 1. Differences in the density distribution pattern of these plant remains can be explained from the depositional context of the cave; they are more abundant toward the lower part of each level. In particular, the plant remains are densely accumulated in black bands running through the lowest part of each level (see Plate 4. 1 in. this volume). The black bands of IVB (Sample Nos. 14, 17, 23, 26, 30) produced more than 15 nutlet fragments, weighting a total of 0.015 gm or more per gram of deposit. From this data, we have estimated the density of Celtis nutlets in the black bands as about one complete grain per two grams of deposit (average weight of carbonized, complete grains from deposits is 0.038 gm). The other deposits, which are thicker, exhibited a lesser density than the black bands; less than 6 nutlet fragments and less than 0.009 gm per gram of sample. In this case, about one complete grain per four grams can be expected in the deposits.

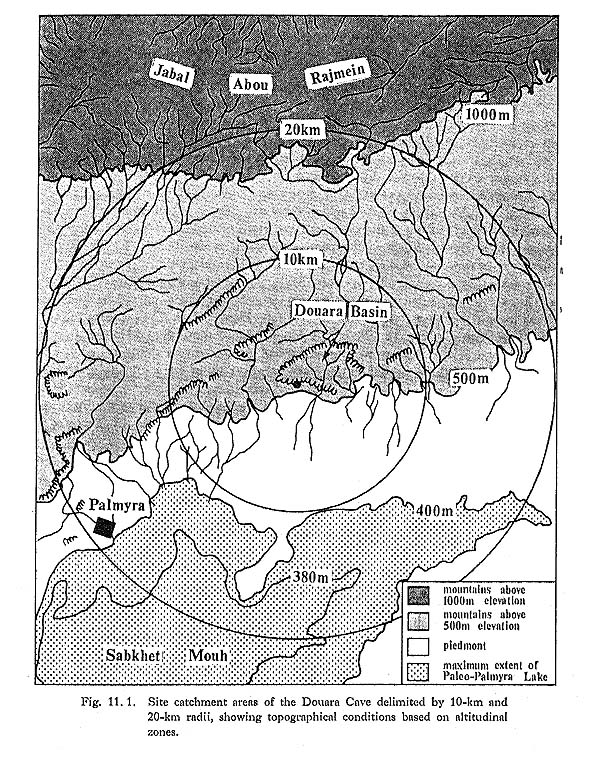

11.4 SITE CATCHMENT MODELStudies of animal and plant remains from Douara Cave suggest that the potential prehistoric resources were considerably different from those presently available. But in order to discuss how the exploitation of these, and other primary resources, such as flint, may have been facilitated by settlement at this location, analysis of the "catchment area" (c.f. Vita-Finzi, and Higgs, 1970) is appropriate. In Fig. 11. 1 areas within 10-km and 20-km radii of the Douara Cave, are the areas assumed to denote the site catchments for the purposes of the present study. Looking first at lithic resources, an excellent source of flint was available in the Douara Basin within the 10-km catchment area. In this basin, a number of flint factory sites have been located, and these have yielded material illustrating a long sequence from Late Acheulian to Pre-Pottery Neolithic (Akazawa, 1975,1979a, b). Such sites are usually located near to the exposed flint beds, and most of these locations in the Douara Basin (see Akazawa, 1979c: Table 14. 1) have produced cores with Levantine Mousterian affinities. Of these, locations 38, 41, and 63 are magnificent examples of Mousterian factory sites and they are only about 1 km. in a straight line from the Douara Cave, crossing a ridge along the southern slope of the Douara Basin. On this evidence, it is possible to argue that Douara Cave was used as the base station for flint factories in the Douara Basin. Topographically, Douara Cave is located in a transitional zone between two diverse environments: mountainous zones to the north and steppic, piedmont settings to the south. The present conditions of the mountainous zones, occupying over 50 percent of the 10-km catchment area, are completely open and very sparsely vegetated, with most of the area taken up by terraces and sloping pediments with stony surfaces, which are cut by a series of steep-sided wadis. Moving further to the north, however, Jabal Abou Rajmein, lying over 1000 m above sea level, is covered with much more greenery, including hundreds of 'botom' trees (personal communication from Hillman and Sakaguchi, 1985). Nevertheless, Jabal Abou Rajmein, around the periphery of a 20-km catchment area based on the Douara Cave was at a certain distance beyond which gathering activities could not be performed habitually by the Douara inhabitants. If we assume that the same vegetation conditions as exist now at Jabal Abou Rajmein existed during the Middle Paleolithic whithin the 10-km catchment area of Douara Cave, then the data from the analysis of the plant remains collected from the cave deposits, especially the abundance of Celtis species, could be easily explained. Celtis, which is completely absent in the Palmyra area today according to Hillman (personal communication, 1985), is a tree adapted to such damper conditions as prevailed today in Anatolia (for C. tournefortii) and the coastal zone (C. austalis) of the Levant. The most southerly penetration of Celtis in the archaeological record known to date is Celtis tournefortii from Mesolithic occupations at Tell Abu Hureyra (approximately 130 km N of Douara Cave) on the Euphrates River (Hillman, 1975: 71). The implication of the Douara evidence, therefore, is that the same climatic conditions as in the Mesolithic occupation at Tell Abu Hureyra may have persisted as far south as the Palmyra area during the Middle Paleolithic occupation. Celtis trees, C. australis and C. tournefortii, appear to have thrived in the area. The presence of Celtis remains at Douara thus suggests that conditions around the cave cannot have been drier, and that there may have been rather more plant and shrub cover than there is today. There would certainly have been forest, including Celtis in the Douara mountainous zones. In other words, vegetational conditions in the mountainous zones would have provided more adequate grazing for the species of herbivorous animals identified in the Douara collection. Nevertheless, the paleoenvironmental conditions near Douara Cave which were indicated by the rodent assemblage, which is assumed to be a more direct source of evidence, were not strikingly different from conditions today, and furthermore, the rainfall cannot have been much higher, according to the remaining faunal assemblage (Payne, 1983). Taking all the evidence together a richer grass and shrub land than today, lying to the south of the cave and occupying about 50 percent of 10-km catchment area can be proposed. This was probably dominated by vegetation of a dry steppe type, including Boraginaceae but there was probably a considerably greater plant cover than there ia today. This would, in turn, mean that the open plain provided richer grazing for herbivorous animals than exists today. 11. 5 CONCLUSIONSThe present data from Douara Cave indicate that it was occupied by two groups of West Asian Neanderthal people, living at different periods and showing significant differences in their lithic technologies. The first inhabitants (level IV), developed a blade industry characterized by prismatic blade core techniques early in the Levantine Middle Paleolithic sequence. The level III inhabitants usually used a prepared (including centripetallyprepared) core technique of typical Levallois type, and also produced many broad oval Levallois flakes. In the depositional context of the cave, these two occupations were separated by a clearly defined layer composed of a wide-spread concentration of weathered limestone fragments suggesting a considerable time gap between the two levels (e.g., Akazawa, 1979c; Endo, 1978). Furthermore, the hearth deposits (levels IVB to IVD) were associated with abundant carbonized plant remains, mostly Celtis nutlet fragments, which make an occupation phase during the early Middle Paleolithic. Although the radiocarbon dates revealed no significant difference between the two levels, the hearth deposit IVB was dated by the fission-track method to 75,000 BP, suggesting that the associated blade industry can be placed in an earlier phase of the Levantine Middle Paleolithic. The Middle Paleolithic Douara inhabitants chose a site in a transitional position between a montane forest zone and open plains with grass and shrubs. Within 10-km catchment area were two essential resources; a good flint supply and adequate grazing for the herbivorous animals on which the Douara inhabitants relied. In fact, the presence of several flint factory sites in the Douara Basin suggests that Douara Cave may have been a base station used while making stone tools at the flint outcrops. This view can be supported by the extremely scarce evidence of retouched tools at the site and the complexity small amount of animal bones. The evidence presented by large quantities of carbonized Celtis fragments suggests summer to autumn occupation since Celtis nutlets become ripe during this season. The Sabkhet Mouh may have provided another source of resources for the Douara inhabitants. According to Sakaguchi's studies, it marks the former existence of the Paleo-Palmyra Lake, and Douara Cave is situated only 10 km from the 400 m elevation which represents the maximum extent of the lake shoreline in the past. Sakaguchi argued that the formation of the Paleo-Palmyra Lake depended upon different environmental and climatic conditions between in the past and present (Sakaguchi, 1978b: 110), but Payne concluded, that the Douara faunal assemblages, reflected long, dry summers, and rainy winters, such that "Middle Paleolithic occupation of the cave could not have been contemporary with the wetter phase that has been postulated while the Palmyra Basin lake was in existence" (Payne, 1983: 104). The modern climate of the Palmyra area is semi-arid, and annual rainfall averages 125 mm, most of which falls between December and March (Abdul-Salam, 1966). In years with higher winter rainfall the Sabkhet Mouh fills with water. As in the winter of 1973 to 1974, when with higher seasonal rainfall was experienced, the Sabkhet Mouh was filled with water much of which remained until the next winter (Sakaguchi, 1978a). Thus even under today's climatic cycle of dry summers and rainy winters the Paleo-Palmyra Lake could have arisen and persisted through years. This would be particularly so if the montane region was covered with more vegetation which would have provided a higher ground water capacity during long, dry summers. Therefore, although much of the evidence is indirect, and many plant remains have still to be identified, the hypothesis that the ecological conditions around the cave were probably different from those prevailing today seems to explain the archaeological data reasonably well. LITERATURE CITED

|