CHAPTER 6

Lithic Assemblages from the Wadi Fan Deposits at Douara

Yoshito Abe, Yoshihiro Nishiaki, and Takeru Akazawa

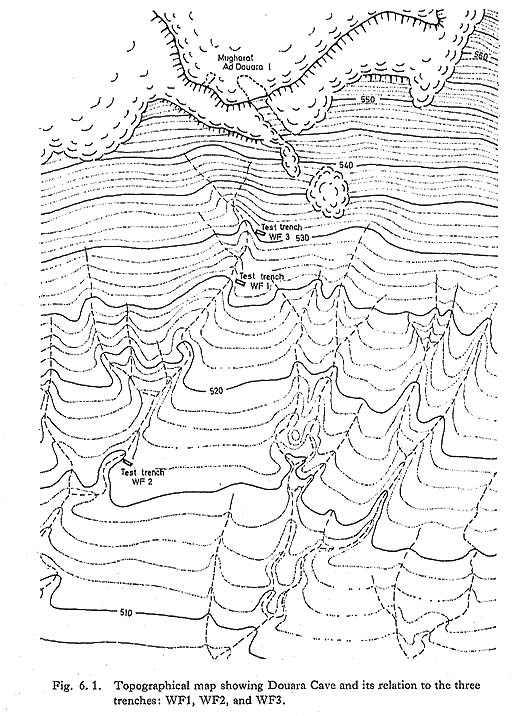

6. 1 INTRODUCTION AND EXCAVATION HISTORYThe collection described in this chapter was obtained from the 1974 excavations of the deposits covering the pediment developed at the foot of the Douara Cave. In arid and semi-arid zones like Syrian desert, specific geological structures named pediments frequently developed. The pediment is situated at the foot of a steeper mountain slope, and is defined as a broad gently sloping bedrock usually covered with a thin deposit of alluvial gravel and sand. According to Sakaguchi (see Chapter 1 in this volume), structures of this type developed everywhere at the foot of the Douara mountain region, and are covered with thin deposits. The 1974 research at Douara was concentrated mostly on the excavation of the cave deposits. In association with the excavation, geomorphological surveys were undertaken to examine the morphological and geological history around the cave. As one of these investigations, three small trenches were dug in the deposits in front of the cave on the mountain slope, along a small Wadi which begins near the cave (see Endo et al., 1978). This deposit was characterized as an alluvial fan by Endo (1978), geomorphologist of the 1974 mission, and hereafter is called the Douara Wadi Fan (WF). The main purpose of the excavation was to examine Wadi Fan deposits and their relation to the cave deposits from the geomorphological viewpoint. Thus, the 1974 excavations were performed in the three trenches designated as WF1, WF2, and WF3 (Fig. 6. 1). The excavation followed a grid system of 1 m × 1 m squares. WFl-trench was composed of six, WF2 of five, and WF3 of seven squares. Each square was excavated in units 10 to 50 cm in depth as an aid in mapping the gross location of materials.

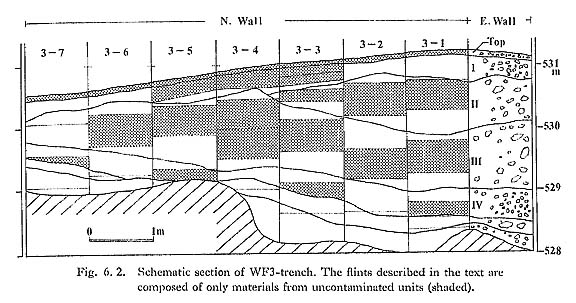

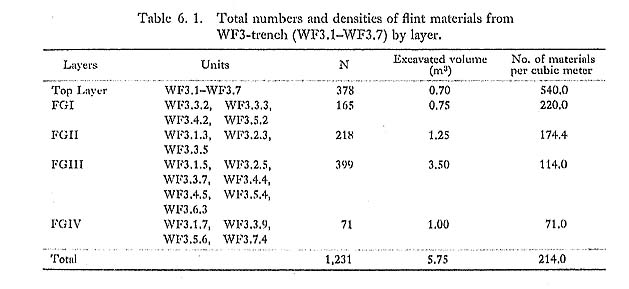

Thousands of flint pieces classifiable as artifacts were collected from these trenches. Brief examination of partial samples showed that occasionally flints of typologically different periods were collected from a single arbitrary level, especially when it was composed of different natural strata, suggesting a possible mixture of different industries. Nevertheless, a number of sampling units were rich in Paleolithic materials. The collection described here is from WF3-trench (Fig. 6, 2; Table 6. 1), which was closest to the cave and produced more flints than the other two trenches.

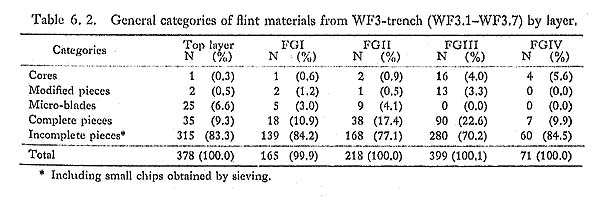

6. 2 DISTRIBUTION PATTERN OF WF3 LITHIC ARTIFACTSWF3-trench was excavated to the bedrock, which was two to three meters from the surface. The stratigraphic sequence was devided into five layers: Top layer and FGI to FGIV from top to bottom (Fig. 6. 2; for more details, see Endo, 1978; Endo et al., 1978). The general categories of lithic artifacts arc shown by stratigraphic level in Table 6. 2.

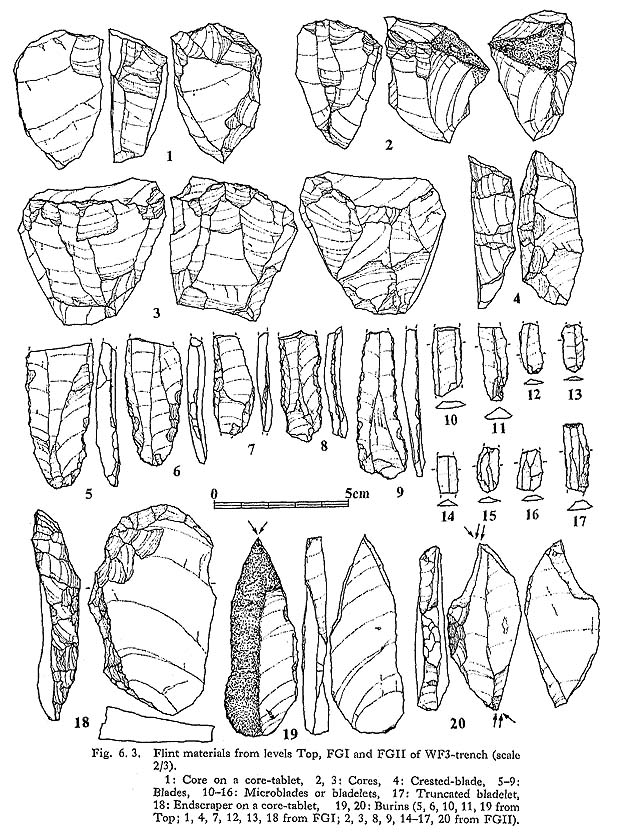

The top layer and FGI to FGIII are the richest in archaeological deposits producing a large quantify of artifacts, while the underlying FGIV was poor, even when consideration is given to the relatively small amount excavated in this layer. The density of the flint collection decreases toward the bottom (see Table 6. 1). Comparing the flints of the different layers, it was found that the Wadi Fan deposits contain two distinctive assemblages: one with a large proportion of Levallois-likc Middle Paleolithic elements in the lower levels, FGIII and FGIV, and an other with a large proportion of bladelet and blade elements, distinctly non Paleolithic, in the upper levels, the Top and FGI to FGII. The collection of lithic artifacts from the upper layers, Top and FGI to FGII, is not homogeneous, suggesting an intermingling of different period assemblages; that is, one is composed of flake elements Middle Paleolithic in character, and the other of blade and bladelet elements Epi-Paleolithic to Neolithic in character (Fig. 6. 3). It is thought that an admixture of this kind originally occurred in the formation of these layers, since the process of stratification was the result of cycles of erosion and deposition, as discussed in the final section of this chapter.

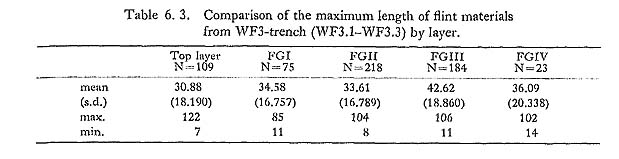

Although the process of formation of the underlying FGIII and FGIV was the same as that of the overlying layers, there is little evidence of admixture of different assemblages, in contrast with that of the overlying layers. The FGIII and FGIV assemblages are of Middle Paleolithic character, with only a few exceptions found in FGIII. 6. 3 PHYSICAL CONDITION OF FLINTS6. 3. 1 Size frequencyTable 6. 3 shows the basic statistics on size (maximum length in mm) frequency of flint artifacts from WF3 (WF3.1-WF3.3)-trench by layer. On comparing these data, it is obvious the size frequency is greatest at the bottom, except for the top layer. Significantly different value can be seen between FGII and FGIII.

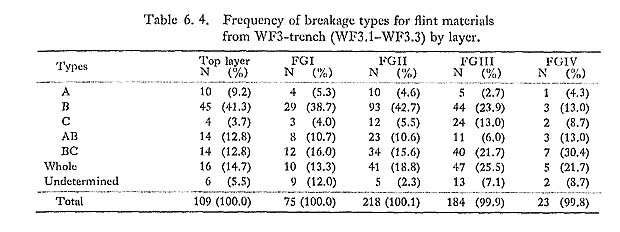

6. 3. 2 Preservation conditionTable 6. 4 shows the frequencies of breakage types (defined in Chapter 5 in this volume; see Fig. 5. 1 in this volume) of flint artifacts by layer. The proportion of fragmentary pieces is greater at the top, and the frequency of well-preserved specimens increases from the upper to lower layers.

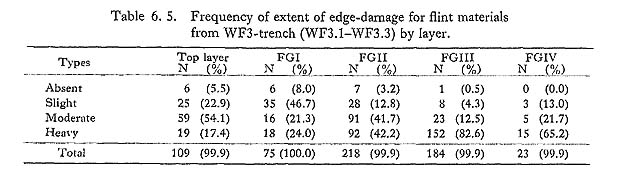

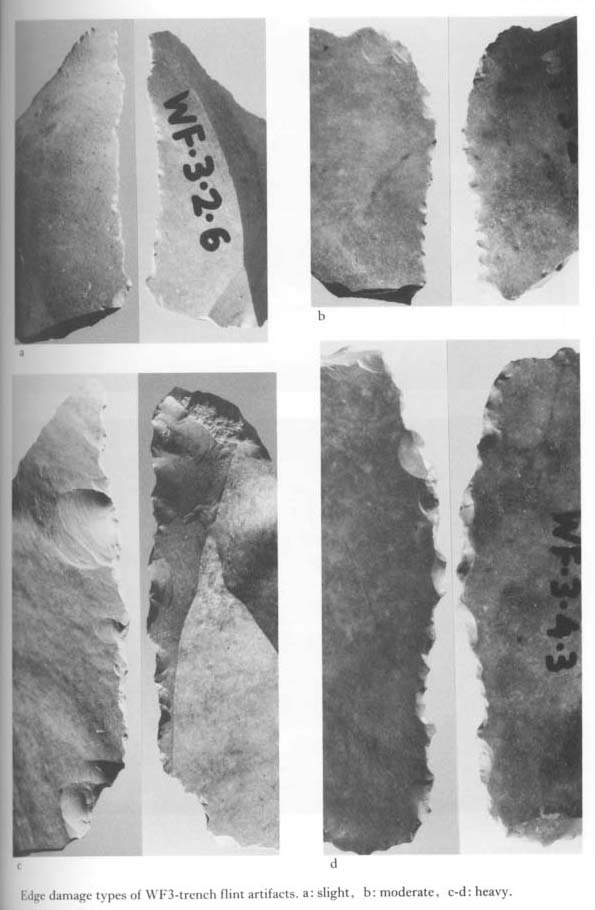

6. 3. 3 Edge damageThe majority of the flakes collected have more or less edge retouching along their margins. This was clearly produced by natural crushing, not by intentional working for the production of scraping edges. Table 6. 5 shows the frequencies of the lithic artifacts classified according to the standardized criteria (Plate 6. 1). The proportion of extensively clamaged pieces is much greater in the lower layers, FGIII and FGIV. The heavily damaged type is the majority (over 80 percent) of the collection examined in FGIII.

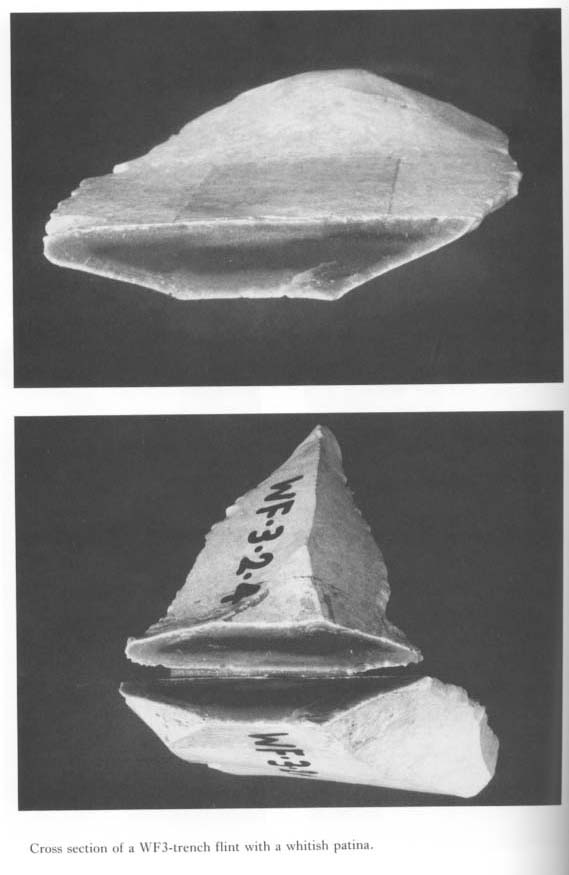

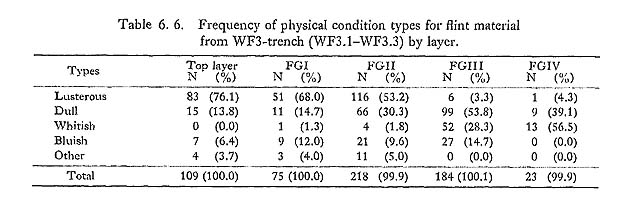

6. 3. 4 Patination colorPhysical condition illustrated by patination color and abrasion also varies with the layers (Plate 6. 2). This is divided into four types: a) lusterous gray to black or brown; b) dull gray and light brown; c) whitish type including lustered and non-lustered; d) bluish type. The bluish color is due to thermal action.

Table 6. 6 is the result of classifying artifacts by patination and abrasion according to the four types defined above. The most prominent feature is the different frequencies of the lusterous type between FGII and FGIII. The lusterous type is much more common at the top, and appears in very low proportion at the bottom. Second, the whitish type is negligible in proportion to the total collection from the upper layers, Top and FGI to FGII, in contrast to the higher frequencies in the FGIII and FGIV collections.

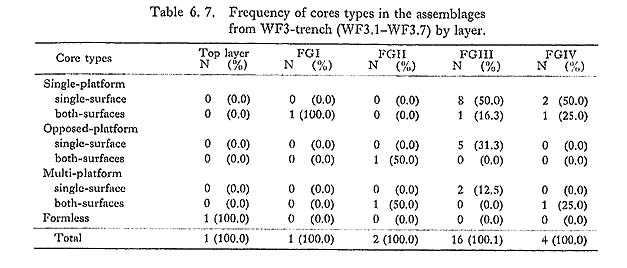

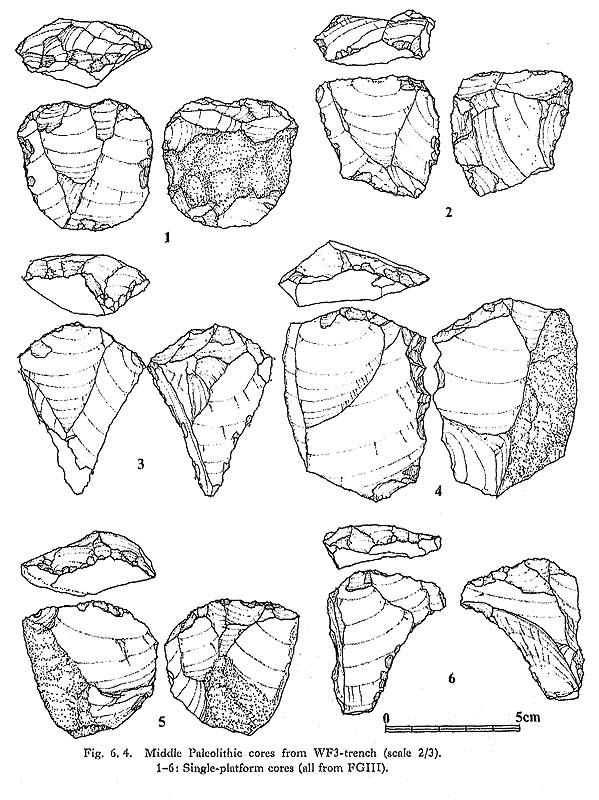

Thus, WF3-trench has yielded material which falls into two major groups, the Middle Paleolithic concentrated at the two lower layers, and the non-Paleolithic in the upper three layers. However, the above two groups intermingle to some extent in some places, especially in the upper layers. The physical condition of flint materials including patination and abrasion is different in the two groups: in nearly every case the older group of flints is more abraded, and quite often has a distinctive patination color such as seen in the dull and whitish types. In conclusion, the materials from FGIII arc homogeneous and numerous enough to provide substantial data for comparison with other assemblages. 6. 4 FGIII ASSEMBLAGE6. 4. 1 CoresA number of cores were collected from the WF3 (WF3.1 to WF3.7) trench, and twenty four were found in well-documented contexts. The frequency distribution of the cores by layer is given in Table 6. 7, showing by far the largest number in FGIII.

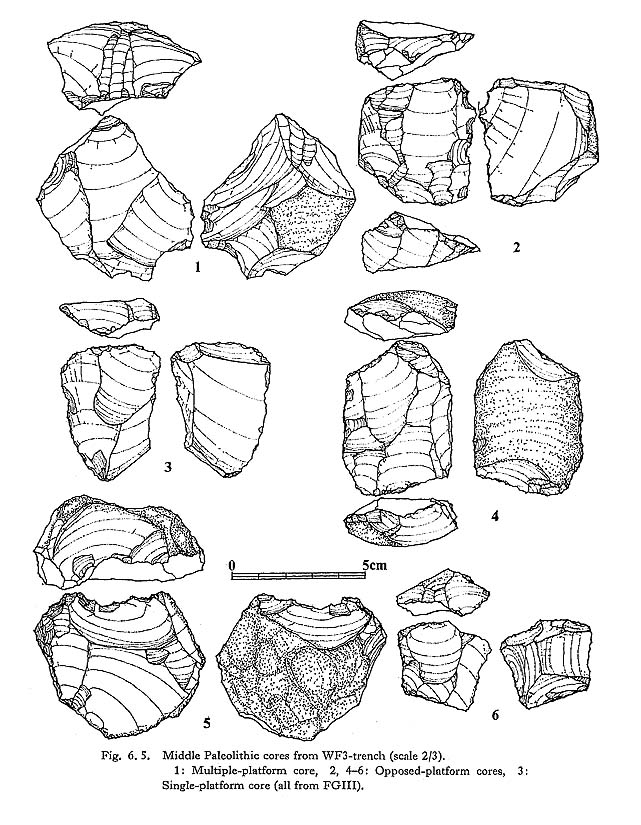

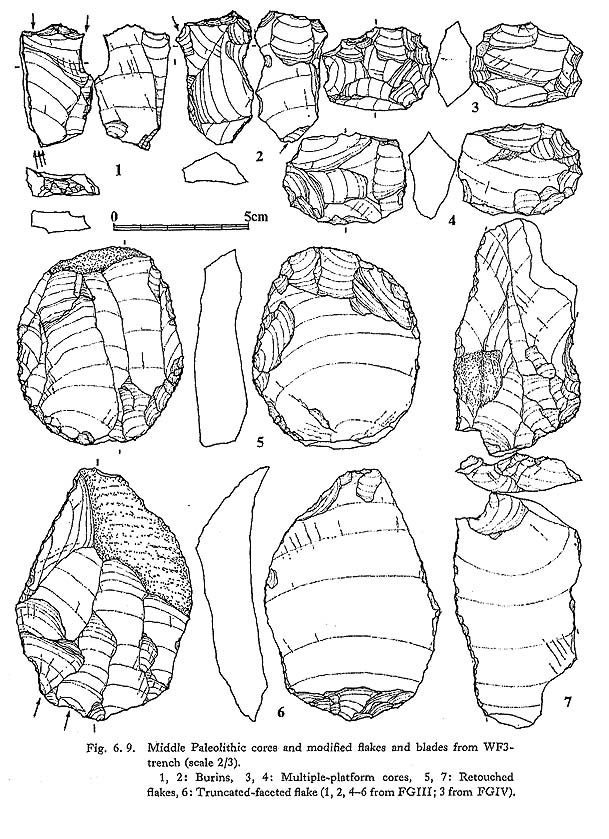

The sixteen cores from FGIII fall into three types according to the number of striking platforms: single-, opposed-, and multiple-platform types. The most dominant type is single-platform cores characterized by having platform at one end (Figs. 6. 4: 1-6, 6. 5: 3). The striking platforms are usually well made by using a series of preparatory flakings and secondary retouchings. These cores are generally characterized by having the flake-and point-type scars on the main surfaces emanate from a single faceted platform. In addition to the single platform preparation scars, there are a series of flaking scars and retouchings along the core margins on both surfaces that were part of the preparation of the core.

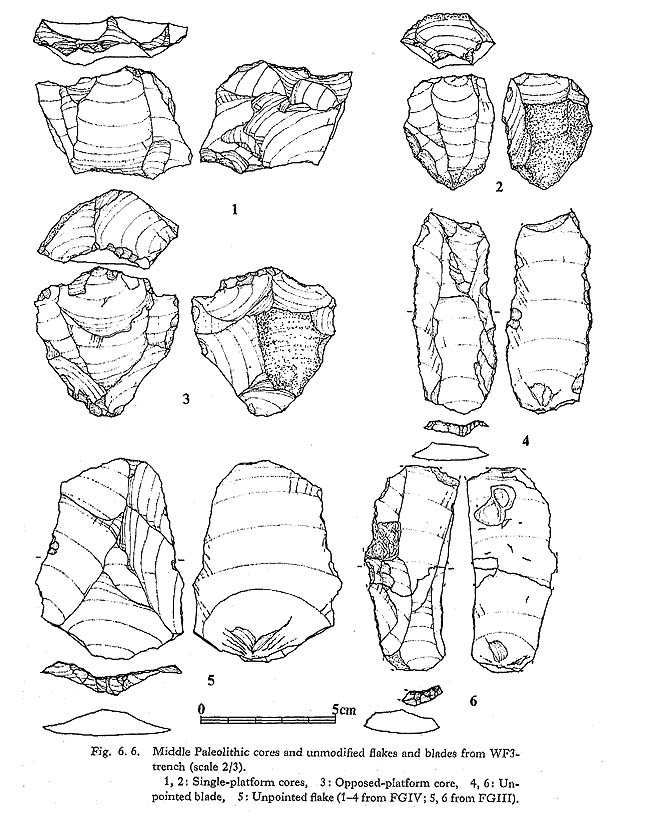

The second most common type is opposed-platform cores. They are characterized by a generally tabular form and a series of flaking scars showing a number of blank removals from both platforms (Fig. 6. 5:2, 4-6). The prepared striking platforms are further faceted by a series of secondary retouchings. Two cores are categorized as multiple-platform types for having multi-directional flaking scars on the main surface (Fig. 6. 5: 6). These cores are rather tortoise-shaped in profile and oval in outline. According to the description so far, the core technique of the FGIII assemblage is not distinct from the typical Levallois type of the Levant. The cores are variable in form, but they share characteristic features: all of the cores have preparatory flaking scars around the perimeter of their main and reverse surfaces, and frequently have cortex on their reverse surfaces. The main and side surfaces generally have centripetal preparatory scars, and the striking platforms are usually well-prepared by secondary facetings. The flaking scars on the main surface of the core are variable in form, but many are characterized by having shaped and pointed scars in outline.

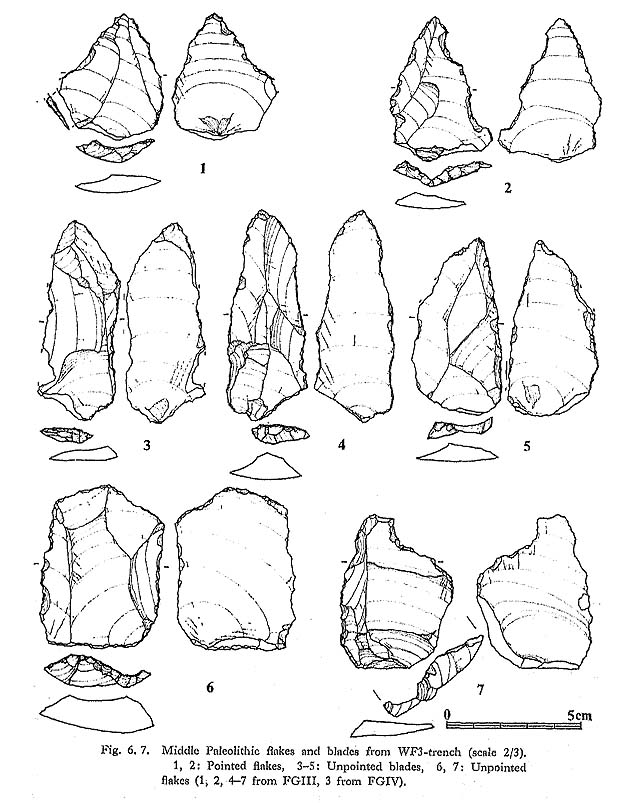

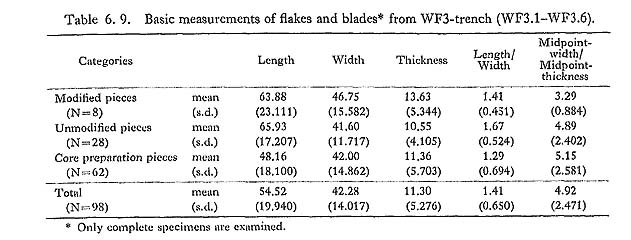

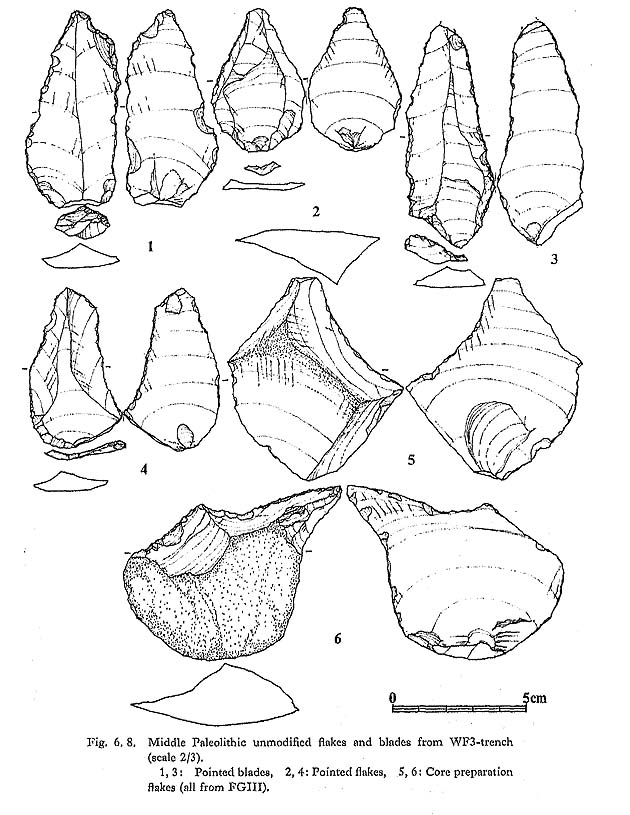

6. 4. 2 Flakes and bladesUnmodified flakes and blades examined here are small in number (see Table 6. 8), as many pieces were heavily damaged. Flakes predominate in the collection examined, and these forms are typical of the Levallois-like flakes and blades in the Levant. That is to say, they have centripetal flaking scars on their dorsal surfaces. The next point to be noted is that pointed flakes of Levallois type, which are characterized by uni-directional flaking scars coming from the butt end, are few in number but not negligible in proportion. Moreover, in nearly every specimen, the striking platform of these pointed flakes is wellprepared by secondary faceting. These descriptions indicate that the flake-blade production technique of FGIII is distinct from the Douara Cave assemblage described in the preceding chapter. This difference is supported by comparisons of several dimensional data obtained from the two assemblages.

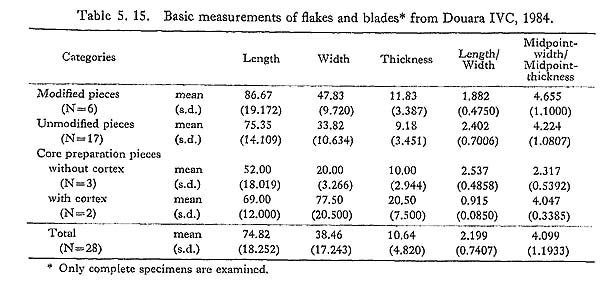

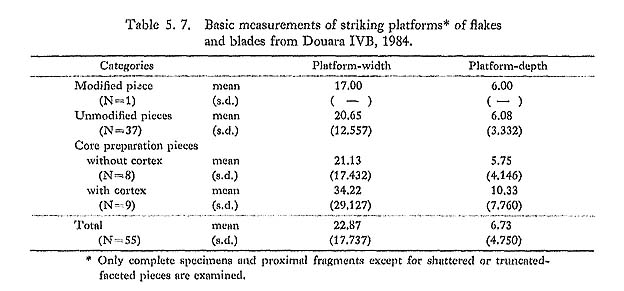

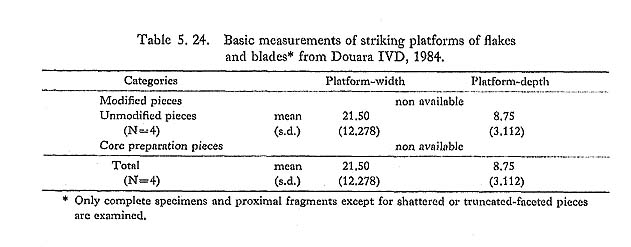

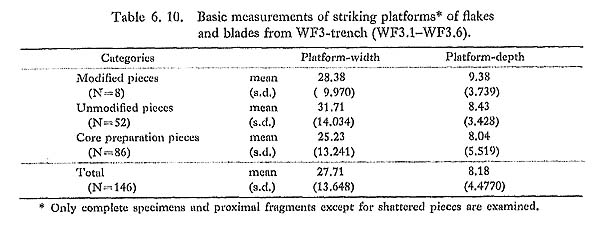

The most remarkable distinction between the two is in the mean value of the length to width ratio (for cave materials, see Tables 5. 6, 5. 15 and 5. 23 in this volume; for WF, see 6. 9). The cave assemblages have a value over 2.00, with a strong tendency for the production of blade blanks, while the FGIII assemblage shows a value of 1.67 resulting from the predominance of flake blanks in the collection. This difference is apparently reflected by the platform size of the unmodified pieces (for cave materials, see Tables 5. 7, 5. 16 and 5. 24 in this volume; for WF, see Table 6. 10). The striking platform of the FGIII collection is significantly wider and thicker than the cave materials.

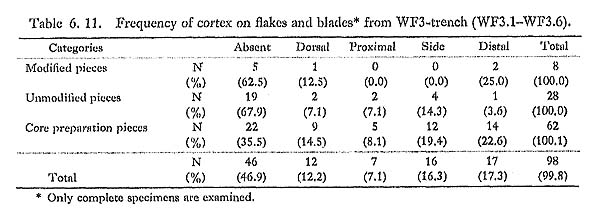

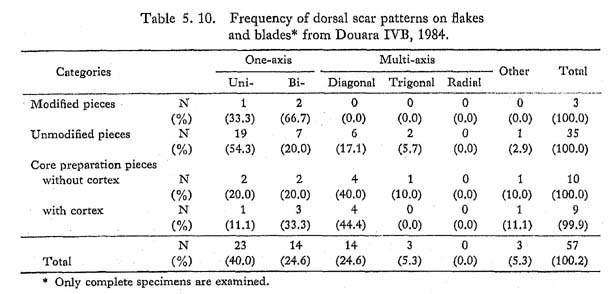

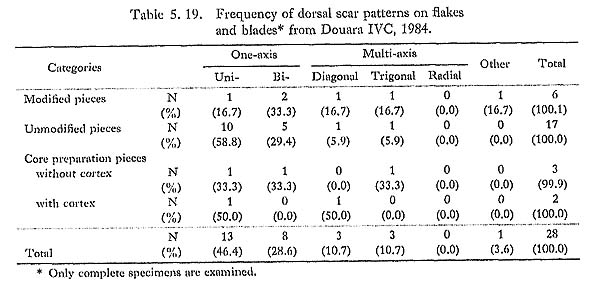

Another difference between the two groups is the technique for flake production used in the preparation of the dorsal surface and the striking platform. Most dorsal scars originate from the proximal end of flakes and blades (Table 6. 12), which coincides well with the cave assemblages. But the proportion of scar directions from the frequency of flakes and blades with radial pattern flaking scars is greater than in the cave assemblages. This difference is also clearly reflected by the dorsal scar patterns, with the proportion of the diagonal type in the FGIII assemblage (Table 6. 13) higher than in the cave assemblages (Tables 5. 10, 5. 19 and 5. 27 in this volume).

The faceting pattern of the striking platforms of flakes and blades is also different for FGIII and the cave. Although the faceted type is the most frequent in both assemblages, the relative quantity is higher in FGIII (Table 6. 14), where they are better prepared.

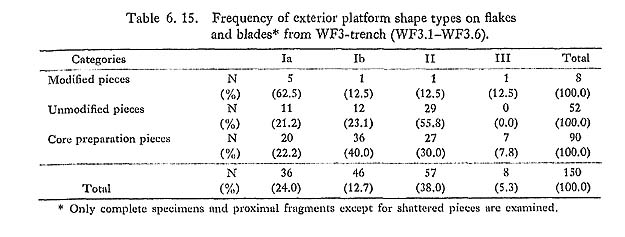

Next, the nature of point selection for the final blow is presented (see Table 6. 15). The classification scheme is based upon the method proposed by Gingell and Harding (1981) and Bergman and Ohnuma (1983). Types I and II are dominant in FGIII; that is, almost all of the flakes and blades are detached by the final blow on a point along the central ridge or between the central ridges of the striking platform. Interestingly, type I is utilized to detach most of the blanks on which the modified pieces were made, but type II is most frequent for the detachment of unmodified pieces.

6. 4. 3 Modified piecesAlmost all of the flakes and blades examined have extensive edge damage along their margins. Clearly this was produced by natural crushing, not by intentional working for the production of scraping edges. The specimens definitely classifiable as tools are burins, truncated-faceted pieces, and retouched pieces, but the quantity is negligible. Burins (Fig. 6.8: 1-2)

There are two burins, with striking similarities. Both are quite similar in the production of the burin edges, and have multiple working edges at both end of the blanks. Further, their working edges with one exception were made by the intersection of retouched truncations and burin spalls. Truncated-faceted piece (Fig. 6.8: 6)Five pieces are classified as secondarily retouched flakes, but are not identifiable as any tool type defined to date. Of these, one piece is classifiable as a truncated-faceted type defined by Nishiaki (1985). 6. 5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONSThe study has not introduced any strictly analytic results in regard to the technology and typology of the Wadi Fan assemblages, since lithic artifacts were collected arbitrarily during an excavation for geomorphological studies of the pediment deposits. The description was restricted to general techno-typological characteristics of the well-preserved artifacts derived from level FGIII. This study is, therefore, only a progress report on the examination of the Wadi Fan assemblages. Nevertheless, the patterns which have emerged can considered as evidence in discussing the FGIII assemblage and its relation to the cave assemblages described in the preceding chapter. The two assemblages, one being FGIII and the other the Douara Cave IVB to IVD assemblages, basically resemble each other, that is to say, both can be categorized as Levantine Mousterian. These assemblages are characterized by the presence of the Levallois technique, although there are differences in frequencies between the two. Nevertheless, it is difficult to establish with certainty a close relationship between these two assemblages. First, core techniques differ between the Wadi Fan and the cave assemblages. Technologically, the FGIII cores are characterized by a high use of the Levallois technique in the strict sense of the word, that is, a frequent occurrence of elaborately faceted striking platforms of permanent type, and of centripetal preparatory scars on the main surface and side preparatory scars along the margins. A very low frequency of these characters is an important characteristic of cave assemblages IVB to IVD. In other words, according to the nomenclature of Levantine prehistory, the classic Levallois core is common in FGIII, but is absent in the cave. Second, blank production techniques are distinct between the Wadi Fan and the cave assemblages. The first remarkable difference is in the manner of blank production. The two assemblages have a frequent occurrence of blade blanks, but they do not share the same features of production: bi-directionally flake-scarred blades with elaborately faceted striking platforms are dominant in the FGIII assemblage, while uni-directionally flake-scarred blades derived from one-axis type cores are dominant in the IVB to IVD assemblages, and their platforms are rather coarsely prepared. That is to say, the patterns which have emerged from the comparative description show that the two assemblages differ in flake-blade proportion, narrowness of blanks defined by length-width ratio, striking platform types, and dorsal scar patterns. These traits are assumed to be related to the core techniques described earlier. In conclusion, there is a marked difference between the assemblages of FGIII and Douara IVB to IVD. Although the two are basically Levallois-like in the blank production technique, the most striking feature of FGIII industry is the dominant role played by the prepared core technique using the classic type Levallois core in the blank production, while the cave assemblages have many points similar to the prismatic blade core technique described by Copeland (1981, 1983). The industry relevant to FGIII assemblage is still not clearly defined in the absence of a complete lithic composition. But the physical condition of the collection, especially patination color, suggests that it is related to that of the cave assemblages. One thing of notable significance is that bluish colored flints are mixed in various ratios with the Wadi Fan assemblages (see Table 6. 6). The frequency is greater from Top to FGIII, but these flints are completely absent in the FGIV assemblage. The bluish flints (Fig. 6. 5: 4, 6) have the same physical condition, especially in patination and abrasion, to the flint material associated with the Middle Paleolithic hearth (levels IVB to IVD) at Douara Cave. Lithic artifacts from the hearth deposits are mostly patinated black to bluish black by thermal action (see Table 5. 3 in this volume). Although the bluish flints of Wadi Fan deposits are patinated slightly lighter in color than the cave ones, these two groups are identical in physical characters, and can be categorized as originally the same material. That is to say, the bluish flints included in the Wadi Fan deposits were secondarily accumulated as a result of erosion that occurred in the cave hearth deposits. This is strengthened by evidence that every piece of bluish flint has extensive edge damage along the margins, produced by natural crushing when the flints rolled down the pediment in front of Douara Cave.

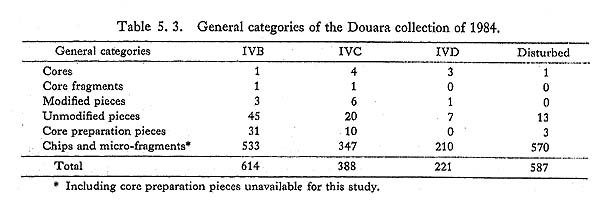

The bluish flints are few in number. The most dominant group of FGIII flints, which are patinated a dull gray or white (see Table 6. 6), are distinct from the IVB to IVD assemblages not only in physical characters but also in technology and typology. In comparing the FGIII assemblage with the other industries of Douara Cave, FGIII has many features similar to the Douara level III of the 1974 excavations (Akazawa, 1979). The most prominent feature of Douara III industry is the frequent use of classic type Levallois technique in core and blank production. If accepting the assumption that Wadi Fan deposits were formed as the result of a cycle of erosion and accumulation of cave deposits, as referred to in an earlier section, it seems probable that the erosion of the Middle Paleolithic deposits in the cave was the major force in the process of FGIII accumulation. It should also be noted that there is no evidence of a living floor, such as a hearth, anywhere in the deposits. LITERATURE CITED

|