PART II

PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY: THE PEOPLE OF JAPAN PAST AND PRESENT

Metrical and Non-Metrical Analyses of Jomon Crania from Eastern Japan

|

Yukio Dodo In Japan, many skeletal remains have been excavated from Jomon sites. Among these, the Tsukumo site in Okayama Prefecture and the Yoshiko site in Aichi Prefecture, both in western Japan, have been particularly rich sources of material (Fig. 1). In other regions, such as Kyushu in the south, the centrally located Kanto area, and Tohoku and Hokkaido in the north, a considerable number of Jomon skeletons have also been collected from rather small shell-mounds. In age, most of these sites range from the Middle phase (ca. third millennium B.C.) to the Final phase (ca. first millennium B.C.) of the Jomon period.

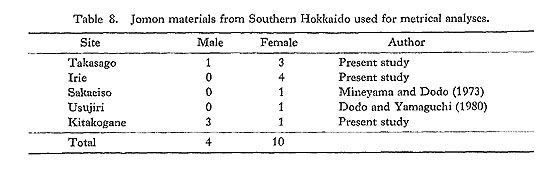

Detailed craniological data based on a large series of materials have so far been presented only on the Tsukumo and Yoshiko skulls of both sexes (Kiyono and Miyamoto, 1926; Kintaka, 1928) and on southern Kanto skulls of the male sex (Suzuki, 1969). Using the craniometric data of these three Jomon series along with data on three modern Japanese series, Yamaguchi (1982) found that the prehistoric Jomon population was morphologically nearly as homogeneous as the present-day Japanese population but that it differed widely in many distinctive osteological features from the modern Japanese. It was not until quite recently that Jomon skeletons from eastern Japan, comprising the Tohoku and Hokkaido regions, were brought in to the investigation of regional differences in the physical characteristics of the widespread Jomon Age population. Comparing the metric data on 29 male Jomon crania from the Tohoku district with data on the more southerly Tsukumo, Yoshiko, and Kanto Jomon cranial series, the present author concluded that the male crania of the Tohoku Jomon people were metrically very akin to those of the Kanto Jomon (Dodo, 1982). Moreover, the characteristics of Jomon skeletal remains from southern Hokkaido have been postulated to be substantially the same as those of the Jomon in Honshu (Yamaguchi, 1981b; Mitsuhashi, 1982). This paper, concerned chiefly with Jomon skulls from the Tohoku district and southern Hokkaido, consists of two parts; the first dealing with the metrical aspects of the crania and the second dealing with their non-metrical aspects. Metrical AnalysesMaterials and MethodsA total of 29 male and 24 female Jomon crania from the Tohoku region were available for measurement. All these crania have been dated to the Middle to Final phases of the Jomon period. The sites of origin, numbers of crania, and authors responsible for measure ments are given in Table 1. The locations of the sites are illustrated in Fig. 2. From southern Hokkaido, four male and 10 female crania from various Jomon sites excavated by our laboratory are available for measurement. The sites and numbers of crania from Hokkaido are listed in Table 8 and their geographical provenances are illustrated in Fig. 2. In age, these sites range from the Middle to Final phases of the Jomon period, with the exception of the Kitakogane site, which has been dated to the Early phase of the Jomon period. For comparison, the Tsukumo and Yoshiko cranial series were combined as representative of the Jomon population of western Japan.

All measurements were based on the definitions of Martin and Saller (1957). The distance measure used was Penrose's shape distance-Cz2 (Constandse-Westermann, 1972). ResultsFirst, averages and standard deviations of principal measurements and indices were calculated for 29 male and 24 female Jomon skulls from the Tohoku district (Table 2). Then, the averages of 22 measurements for each sex were compared with the averages for the western Japan Jomon, the Hokkaido Ainu, and the modern Tohoku Japanese (Tables 3 and 4).

Based on Tables 3 and 4, Penrose's shape distances were computed for each sex in the Tohoku Jomon sample, as shown in Table 5, For both sexes, Tohoku Jomon measurements were far closer to those of the western Japan Jomon than to those of the Hokkaido Ainu. They were, however, apparently closer to the Hokkaido Ainu than to the modern Japanese. The mutual relationships among the Tohoku Jomon, western Japan Jomon, and Hokkaido Ainu are schematically illustrated in Fig. 3.

Penrose's shape distances from the western Japan Jomon and Hokkaido Ainu were computed for each individual skull of the Tohoku Jomon that was fairly well preserved. This was done to determine which population the individual skulls most resembled. As shown in Table 6, within the male series, 17 out of 20 Tohoku Jomon crania (85.0%) showed a closer similarity to crania of the western Japan Jomon, while the remaining three crania (15.0%) showed a closer similarity to those of the Hokkaido Ainu. Of the female crania, seven out of 11 (63.6%) showed a closer affinity to those of the western Japan Jomon, while the remaining four crania (36.4%) displayed a closer resemblance to those of the Ainu, as shown in Table 7.

As previously indicated, four male and 10 female Jomon crania from southern Hokkaido are available for measurement. Averages and standard deviations of principal measurements and indices were calculated and the results are given in Table 9. Penrose's shape distances from the Hokkaido Jomon were computed for each sex on the basis or Tables 3, 4, and 9, as shown in Table 10. In the male series, the Hokkaido Jomon was closest to the western Japan Jomon and farthest from the modern Japanese, with the Hokkaido Ainu lying in between the two. In the female series, on the other hand, the Hokkaido Jomon was closest to the Hokkaido Ainu, next closest to the western Japan Jomon, and farthest from the modern Japanese.

In order to test these results, Penrose's shape distances from the western Japan Jomon and Hokkaido Ainu were computed for each individual skull of the Hokkaido Jomon series. The results for the male series are given in Table 11 and those for the female series in Table 12. In the male series, three out of four crania were closer to those of the western Japan Jomon than to those of the Hokkaido Ainu and only one skull showed a closer relation ship to those of the Ainu. In contrast, in the female series, eight out of 10 crania showed a stronger similarity to the crania of the Hokkaido Ainu, while the remaining two crania showed a closer affinity to the crania of the western Japan Jomon.

DiscussionFrom the results just described, and those of the present author's previous work (Dodo, 1982), it can safely be concluded that the characteristics of Tohoku Jomon crania of both sexes are nearly the same as those of Jomon crania from western Japan. It is apparent that in both sexes the Tohoku Jomon are far closer to the western Japan Jomon than to the Hokkaido Ainu. However, when crania of the modern Japanese are brought into the comparison, the Jomon series as a whole shows an apparently closer similarity to the Ainu than to the modern Japanese. A close resemblance in skeletal morphology between the Jomon and Ainu has been repeatedly postulated for nearly a hundred years (e.g., Koganei, 1890, 1894; Howells, 1966; Yamaguchi, 1967, 1973, 1982; Dodo, 1982). This resemblance is supported by the above observations, and confirmed by the evidence of non-metric cranial variants to be described in a following section of this article. In southern Hokkaido, the male Jomon crania were closest to those of the western Japan Jomon, whereas the female crania were closest to those of the Hokkaido Ainu. In view of these results, it is possible to postulate that, although the cranial characteristics of the male Hokkaido Jomon are substantially the same as those of the Jomon in Honshu, the cranial features of the female Hokkaido Jomon are slightly different from those of tlie female Jomon in Honshu. The female Hokkaido Jomon definitely are more Ainoid. The tentative conclusion of previous workers (Yamaguchi, 1974, 1981b; Mitsuhashi, 1982) that most of the Jomon skeletal remains from Hokkaido are nearly indistinguishable from those of Honshu should therefore now be viewed with some reservation. However, since the size of the sample is not large enough to warrant strong conclusions, further research will be required regarding this problem. Non-Metrical AnalysesIn Japan, the frequencies of non-metric minor cranial variants have been until now reported only for modern people: the Hokkaido Ainu, the Tohoku and Kanto Japanese (Dodo, 1974), the Kinki Japanese (Akabori, 1933; Mouri, 1976), and the Unko-in Temple Japanese of the Edo period (Dodo, 1975). With regard to non-metric traits in archaeological populations, Ossenberg (1986) first investigated Jomon cranial series, mostly from western Japan. Immediately following her investigations, the present author examined cranial series from archaeological sites in eastern Japan from the same point of view. This category of study has not until now been considered in reconstructions of the population history of Japan. Materials and MethodsAs a first step in the analysis, the presence or absence of 21 non-metric variants was recorded for each cranium (Table 13). Then, the skull-incidences of these variants were examined in a combined series of both sexes for the eastern Honshu Jomon, Hokkaido Ainu, and modern Tohoku and Kanto Japanese. The eastern Honshu Jomon series consists of 90 skulls of both sexes derived from the Tohoku and Kanto regions. The data on the Ainu and modern Tohoku and Kanto Japanese are the same as those described in my previous study (Dodo, 1974). The sites and numbers of crania are given in Table 14.

The skulls of the Ebishima, Miyano, Sanganji, Horinouchi and Ubayama sites are housed in the National Science Museum, Tokyo. Those of the Hosoura site are deposited at Osaka University. Those of the Usozawa, Satohama, Aoshima and Kawakudari sites are kept at Tohoku University. The skull from the Kashikodokoro site is kept in the University Museum of the University of Tokyo. The remaining crania from the Otsuke, Kuma'ana, Tagara, Minamisaichi and Maehama sites were obtained during the present author's field work and are at the Sapporo Medical College. The crania of the Hokkaido Jomon series were all excavated by our laboratory and are also in the Sapporo Medical College. A total of 41 skulls were available for non-metric analysis (Table 16).

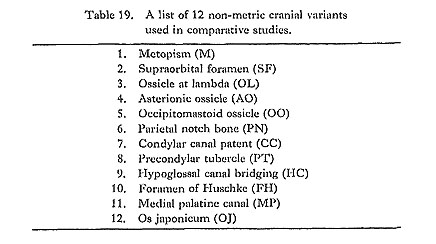

In an additional comparison of the Japanese materials with crania from the Asian continent, 12 non-metric cranial variants whose criteria of presence or absence seemed to be common in all comparative series were used, as shown in Table 19.

For the distance measure, C.A.B. Smith's Mean Measure of Divergence (MMD) was applied, that is:

Using a matrix of Smith's MMDs, a cluster analysis and a principal co-ordinates analysis were attempted. The group-average method was employed for the cluster analysis, while the principal co-ordinates analysis was only an approximate application. These statistical analyses were kindly conducted by Dr. Y. Mizoguchi of the National Science Museum, Tokyo. ResultsSkull-incidences of 21 non-metric minor cranial variants among the eastern Honshu Jomon, Hokkaido Ainu, and modern Japanese are presented in Table 15. Based on this table, Smith's MMDs were computed among the eastern Honshu Jomon, Hokkaido Ainu, and modern Japanese. The results are schematically illustrated in Fig. 4. The Jomon and Ainu are much closer than the Jomon and modern Japanese or the Ainu and modern Japanese.

The incidence of non-metric variants was also examined for the Hokkaido Jomon series, comprising a total of 41 skulls. Because of the small size of the sample, however, Smith's Mean Measure of Divergence was calculated based on the side-incidences of the variants (Table 17). Since the Hokkaido Jomon series was closest to the eastern Honshu Jomon, for the sake of increasing sample size the two were combined into one series, the eastern Japan Jomon. In Table 18, the skull-incidences of 21 non-metric cranial variants among the eastern Japan Jomon are given. Smith's MMDs among the eastern Japan Jomon, Hokkaido Ainu, and modern Japanese are schematically illustrated in Fig, 5. Note that there is prac- tically no difference between the results portrayed in Figs. 4 and 5. The eastern Japan Jomon series was also far closer to the Ainu than to the modern Japanese.

In order to examine genetic relationships among the eastern Honshu Jomon population sample, Asian Mongoloid groups, and other Japanese population samples, the skull incidences of 12 non-metric cranial variants were compared, as shown in Table 20. Smith's MMD from the eastern Honshu Jomon based on skull-incidences was computed for seven population samples from Japan and the Asian continent. The results are given in Table 21. The eastern Honshu Jomon was far closer to the Hokkaido Ainu than to any of the other six populations of Mongoloid stock. In Fig. 6, these results are compared with those of Mahala nobis' D square presented by Yamaguchi (1981a). The two analyses can be seen to roughly correlate with each other, especially with regard to the close relationship between the Jomon and Ainu.

A matrix of Smith's MMDs was made in order to clarify reciprocal distances among the eastern Honshu Jomon, Hokkaido Ainu, eastern Japan Modern, western Japan Modern, and Unko-in Temple Edo period samples from Japan, and Korea Modern, North China Modern, and Mongol Modern samples from the Asian continent (Table 22). On the basis of this matrix, a cluster analysis was attempted. The results are illustrated in Fig. 7, which shows the Jomon and Ainu lumped into one cluster, with the remaining six population samples loosely joined into another cluster.

Next, again on the basis of the matrix shown in Table 22, a principal co-ordinates analysis was carried out by Dr. Yuji Mizoguchi, the results of which are illustrated two-dimen sionally in Fig. 8. The first two principal components explain more than 90% of the total variance. The results of this analysis were almost the same as those of the cluster analysis: the Jomon and Ainu were lumped into one group, while the remaining six populations were loosely tied into another group that in turn fell into Japanese and continental Asian sub groups.

DiscussionClose resemblance between the Jomon and Ainu in cranial characteristics is demon strated by the evidence of non-metric minor cranial variants shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The Jomon population is far closer to the Amu than to the modern Japanese in its incidence pattern of non-metric cranial variants. This is one of the most important findings of this study, since all recent Mongoloid populations thus far examined have shown almost no affinity with the Ainu with regard to the incidence pattern of non-metric cranial variants (Yamaguchi, 1977). Despite the use of different kinds of non-metric variants and materials from those employed by the present author, Ossenberg (1986) obtained almost the same results; that is, the Jomon series was found to be much closer to the Ainu than to the modern Japanese. In view of these results, it can be stressed that a strong kinship exists between the Jomon and Hokkaido Ainu. This is further supported by the similarities between Mahalanobis' D square and Smith's MMD shown in Fig. 6. The results of both the cluster analysis and the principal co-ordinates analysis were nearly the same. It should be noted here that in both analyses the modern Japanese popu lation samples were lumped in with such classic Asian Mongoloid groups as Korean, North Chinese, and Mongolian, Ossenberg also attempted a cluster analysis of four Japanese and seven Siberian population samples. In her dendrograph, two modern Japanese samples were lumped with classic Siberian Mongoloid groups, while the Jomon-Ainu samples were isolated from all other population samples. The results correspond almost completely with those of the present paper. Within Japanese population samples, Ossenberg observed the following gradation of Smith's MMDs: Jomon-Ainu 47.9, Jomon-Kanto Japanese 133.5, Jomon-Kinki Japanese 168.0. This gradation was wholly consistent with that of Mahalanobis' D square reported by Yamaguchi (1981a). Although Ossenberg considered such a gradient of biological distances to be consistent with the theory that hybridization between Jomon and conti nental immigrants during the Yayoi and succeeding periods played an important role in Japanese population history, no such geographical dine was clearly observable in the present study (Fig. 6). From the results of the present statistical analyses, it can be suggested that the modern Japanese and Asian continent populations belong to the classic Mongoloid category, whereas the Jomon and Ainu, isolated from other classic Mongoloid groups and seemingly much less Mongoloid, more likely belong to the so-called Proto- or Pre-Mongoloid category. More over, the Ainu of Hokkaido appear to be direct descendants of the Jomon, as suggested by Turner (1976), Brace and Nagai (1982), Yamaguchi (1982), and Hanihara (1983). However, further conclusions with regard to the population history of Japan must be withheld u ntil other cranial series of historic and prehistoric times, such as those of the medieval Kamakura, protohistoric Kofun, and Aeneolithic Yayoi periods, are examined by means of non-metrical analyses. Summary and ConclusionIn the first part of this paper, measurements of Tohoku Jomon crania were compared with those of the western Japan Jomon, Hokkaido Ainu, and modern Japanese. Penrose's shape distances based on cranial measurements revealed that the Tohoku Jomon series was far closer to the western Japan Jomon than to the Hokkaido Ainu and that it differed little from the western Japan Jomon in both sexes. By metrical analyses, however, both Jomon series did show a closer similarity to the Hokkaido Ainu than to the modern Japa nese. With regard to the Jomon from southern Hokkaido, Penrose's shape distances showed that the male series was closer to the western Japan Jomon than to the Hokkaido Ainu, whereas the female series was a bit closer to the Hokkaido Ainu than to the western Japan Jomon. The reason for this inconsistency requires clarification. In the second part of the paper, the skull-incidences of 21 non-metric minor cranial variants among the eastern Honshu Jomon were compared with those among the Hokkaido Ainu and modern Japanese. Smith's Mean Measure of Divergences among these three cranial series showed the Jomon to be far closer to the Ainu than to the modern Japanese. These results were wholly consistent with those of previously published metrical analyses. The Hokkaido Jomon differed little from the eastern Honshu Jomon in the incidence pattern of non-metric cranial variants. Smith's Mean Measure of Divergence from the eastern Honshu Jomon based on the skull-incidences of 12 cranial variants was computed for seven population samples from Japan and the Asian continent. The Jomon sample was far closer to that for the Ainu than to any of the remaining six population samples of Mongoloid stock. Two statistical analyses, one a cluster analysis and the other a principal co-ordinates analysis, were carried out based on a matrix of Smith's MMDs among Jomon, Ainu, eastern Japan Modern, western Japan Modern, and Unko-in Temple Edo period crania in Japan, and Korea Modern, North China Modern, and Mongol Modern crania on the Asian continent. The results of these two statistical analyses correlated almost completely; that is, all the modern Japanese population samples were lumped into classic Asian Mongo loid groups, whereas the Jomon and Ainu were isolated from all other Mongoloid popu lation samples. From these results, it was suggested that the Japanese and Asian continent populations belong to the classic Mongoloid category, whereas the Jomon and Ainu, much less Mongoloid, more likely belong to the Proto- or Pre-Mongoloid category. Furthermore, it was suggested that the Hokkaido Ainu must be direct descendants of the ancient Jomon people of Japan. AcknowledgementsI would like to thank the following persons for permission to study the Jomon crania in their charge: Dr. S. Kanda of the Hyogo College of Medicine; Dr. H. Masai of Osaka University Medical School; Drs. B. Yamaguchi and H. Sakura of the National Science Museum, Tokyo; Drs. H. Suzuki, K. Hanihara, and T. Akazawa of the University of Tokyo; Dr. T. Kodaka and Mr. S. Otomo of Tohoku University; Dr. K. Mitsuhashi of Sapporo Medical College. Appreciation is also due to Dr. K. Hayashi of Hokkaido University; Mr. T. Nishimoto of the National Museum of Japanese History; Mr. K. Koikawa and Mr. M. Abe of the Miyagi Board of Education; Mr. T. Odano and Mr. T. Kumagai of the Iwate Prefectural Museum, and Mr. N. Oshima of Sapporo Medical College, for providing me with the opportunity to excavate human skeletal remains of the Jomon period. I am also greatly indebted to Dr. Y. Mizoguchi of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, for kindly carrying out the cluster and principal co-ordinates analyses reported in this paper. References

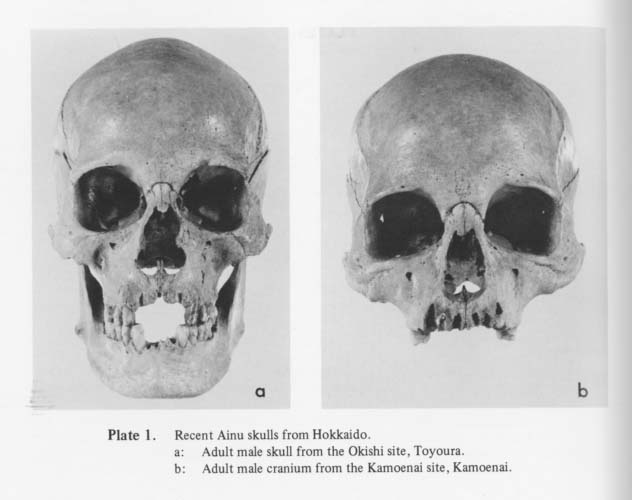

PLATES

|