Family Scaridae: Budai-ka

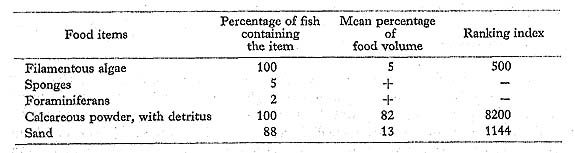

As noted by Hobson (1974), the diet of scarids remains controversial. Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) found coral polyps and algae along with large amounts of calcareous powder and coral skeletal fragments in all of four scarids that they examined in the Marshall Islands. In contrast, Randall (1967) in the West Indies, Hobson (1974) in Hawaii, and Gushima (1981) at Kuchierabu Island, Japan, did not find coral polyps in

any scarids examined, and concluded that they scrape benthonic algae from the surfaces of dead corals and rocks.

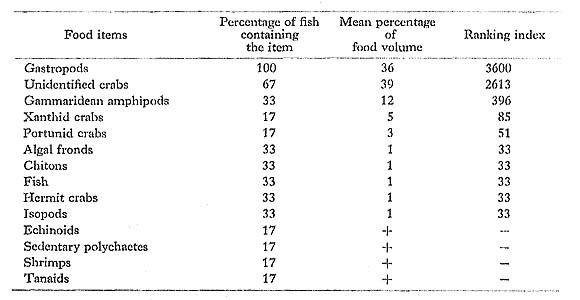

Scarus chlorodon Jenyns: Hoshi-budai

FUMT-P 4126, 4282; 6 specimens; spring and summer; 59-90 mm SL.

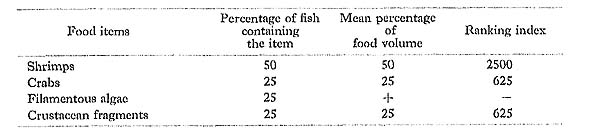

Scarus ghobban (Forsskål): Hi-budai

FUMT-P 4125, 4283; 15 specimens; spring and summer; 51-113 mm SL.

Scarus oviceps Valenciennes: Hime-budai

FUMT-P 4284; 4 specimens; spring; 57-69 mm SL.

Scarus sordids Forsskål: Hage-budai

FUMT-P 4124, 4285; 41 specimens; spring and summer; 53-108 mm SL; 1 empty.

Scarus venosus Valenciennes: Kurosuji-budai

FUMT-P 4286; 7 specimens; spring; 96-119 mm SL; 1 cmpty.

Scarus sp.

FUMT-P 4287; 3 specimens; spring; 90-97 mm SL; 1 cmpty.

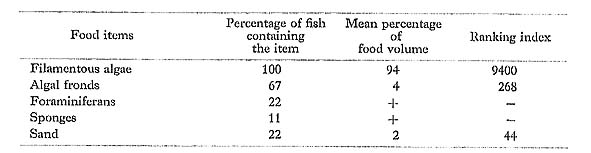

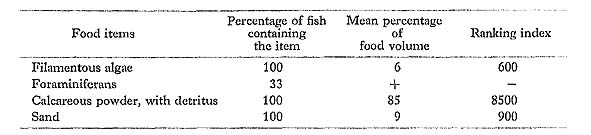

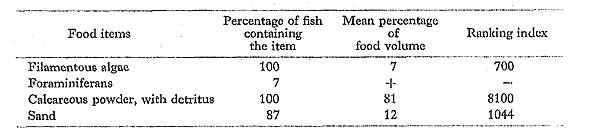

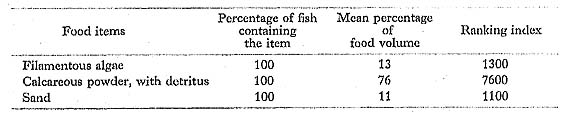

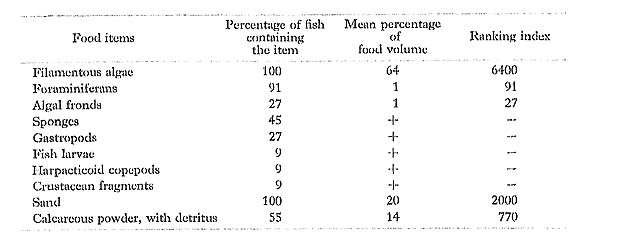

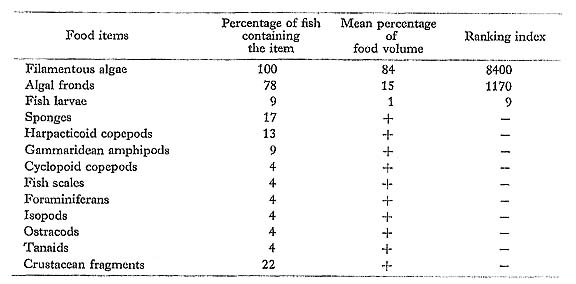

Remarks on the food habits of scarids are summarized here. All six scarids at Minato-gawa had taken filamentous algae and detritus mixed with large amounts of calcareous powder. We found no evidence that any of these species feed on coral polyps. In addition to these food data, we observed that the scarids actively scrape the surfaces of dead corals and rocks with their parrot-like beaks as if to avoid the living corals. Obviously, their food and feeding characteristics indicate that they are herbivores, scraping the ben thonic algae.

At Minatogawa the scarids frequently hover close to the coral and rocky reefs in small to large mixed schools with other herbivorous fishes Buch as acanthurids and siganids, These mixed schoolings have been recognized to be one of the feeding strategies of the foraging herbivorous fishes (Alevizon, 1976; Robertson et al., 1976; Gushima and Murakami, 1979). These fishea in schools gain the great advantage of feeding easily on benthonic algae which are actively defended by highly aggressive territorial poma-centrid fishes. While the pomacentrids attempt to chase out a few members of the schools, the remainder are able to feed on the algae without difficulty (Alevizon, 1976).

Family Pomacanthidae: Kinchakudai-ka

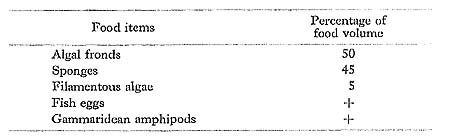

Pomacanthus semicirculatus (Cuvier): Sazanami-yakko

FUMT-P 4033; 1 specimen; summer; 102 mm SL.

P. semicirculatzis had eaten algae and sponges in about equal amounts. In the West Indies, Randall and Hartman (1968) examined the stomach contents of two species of the genus Pomacanthus, P. arcuatus and P. paru, and of two species of the related genus Holacanthus, H. ciliaris and H. tricolor, and found that sponges comprised over 70% of the food for the former two species and over 95% for the latter two. Hobson (1974) also reported that H. arcuatus in Hawaii feeds almost exclusively on sponges.

Family Chaetodontidae: Chochouo-ka

Chaetodontids occur mostly on coral reefs either as solitary individuals, as pairs, as small groups of three or more, and as relatively large aggregations (Hobson, 1974; Reese, 1975; Burgess, 1978; Sano, personal observation). Reese (1975) described the social groupings of the different species, intra- and interspecific agonistic interactions, and feeding for 20 chaetodontids on the basis of field observations at three localities in the Pacific Ocean.

Chaetodon auriga Forsskål: Toge-chochouo

FUMT-P 4023, 4229; 13 specimens; spring and summer; 37-81 mm SL.

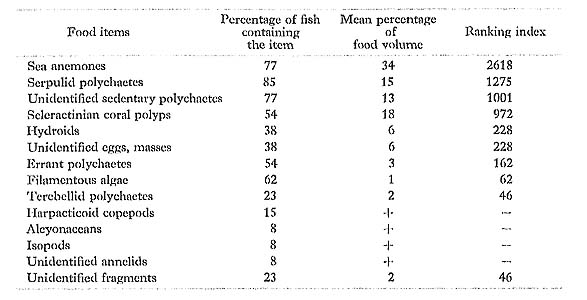

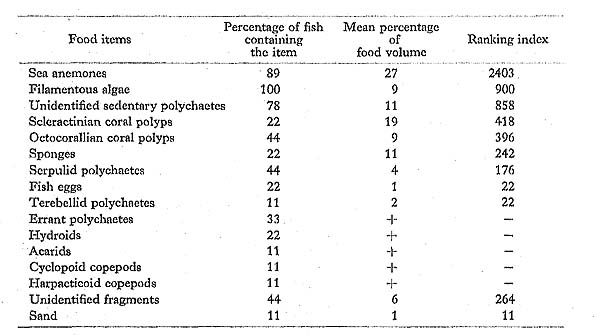

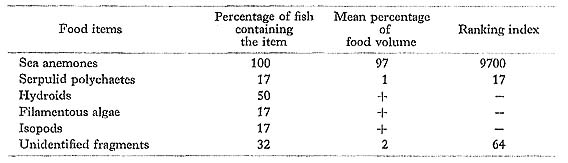

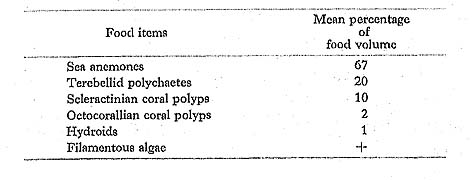

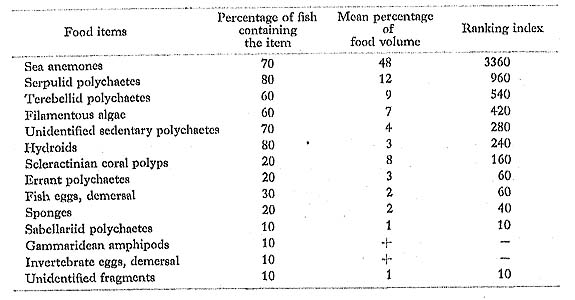

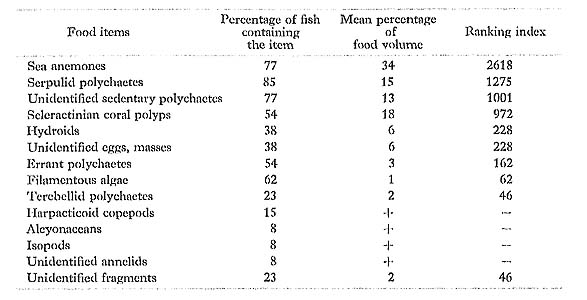

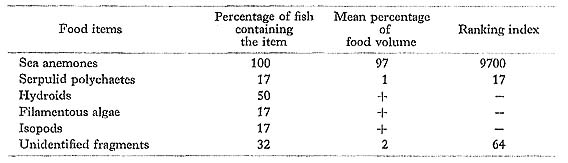

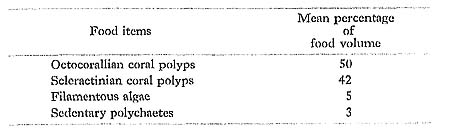

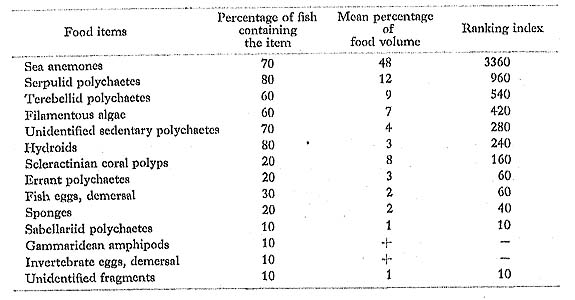

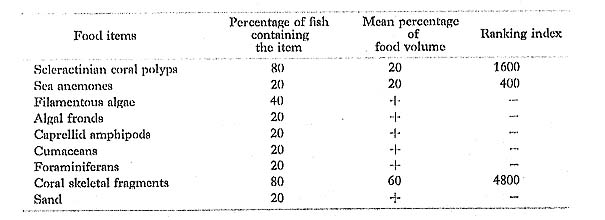

C. auriga had taken mostly sessile invertebrates, especially sea anemones and seden tary polychaetes. Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) in the Marshall Islands and Reese (1975) reported it to be an omnivore which feeds on filamentous algae and benthonic inverte-bratca such as polychaetes. However, we found that this species at Minatogawa hardly preys on algae. Our result fits closely with those obtained by Hobson (1974) in Hawaii and Harmelin-Vivien and Bouchon-Navaro (1981) in the Red Sea, where C. aurigaobtains most of its food by tearing off pieces of large seasile invertebrates, cspccia alcyonarians, sedentary polychaetea, and scleractinian corals.

Chaetodon auripes Jordan et Snyder: Chochchouo

FUMT-P 4022, 4230; 10 specimens; spring and summer; 52-89 mm SL.

Most of the prey of C. auripes were sessile invertebrates, especially sea anemones.

Chaetodon baronessa Cuvier: Mikado-chochouo

FUMT-P 4032, 4241.

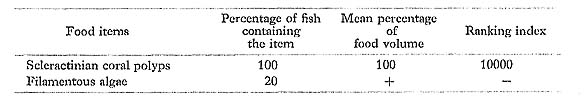

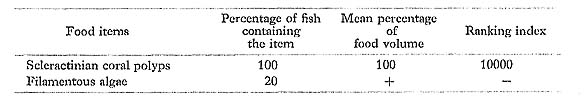

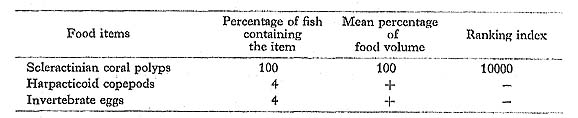

A single specimen (52 mm SL) collected from a reef rich in staghorn Acropora during the spring had taken only scleractinian coral polyps, along with much mucus; another (51 mm SL) also captured in the same habitat during the summer contained the same prey in the stomach.

Chaetodon bennetti Cuvier: Umizuki-chochouo

FUMT-P 4031, 4231; 5 specimens; spring and summer; 41-69 mm SL.

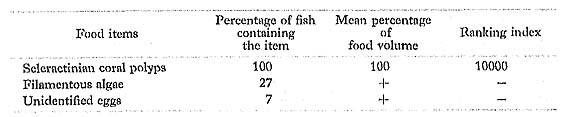

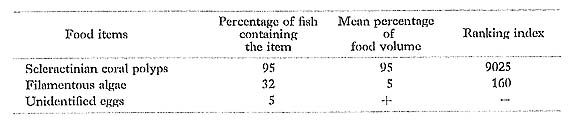

All specimens of C. bennetti examined had stomachs full of scleractinian coral polyps, along with much mucus.

Chaetodon citrinellus Cuvier: Goma-chochouo

FUMT-P 4021, 4232; 9 specimens; spring and summer; 60-91 mm SL; 1 empty.

C. citrinellus had fed mostly on sessile invertebrates, especially anthozoans and seden tary polychaetes, along with some filamentous algae, which are much the same prey as taken by the same species in the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960).

Chaetodon ephippium Cuvier: Seguro-chochouo

FUMT-P 4025, 4233; 6 specimens; spring and summer; 47-89 mm SL.

C. ephippium had fed mostly on sessile invertebrates such as sponges and scleractinian corals. Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) found mainly coral polyps and fine filamentous algae in the ten larger specimens (123-160 mm SL) that they examined in the Marshall Is lands. Similarly, Reese (1975) observed this species grazing on the surfaces of living corals and dead coral rocks at Heron Island and Eniwetok Atoll, and thus classified it as an omnivore feeding on coral polyps and filamentous algae. However, these two results contrast with ours at Minatogawa, where it scarcely feeds on algae.

Chaetodon kleinii Bloch: Mizore-chochouo

FUMT-P 4234; 3 spceimens; spring; 64-94 mm SL.

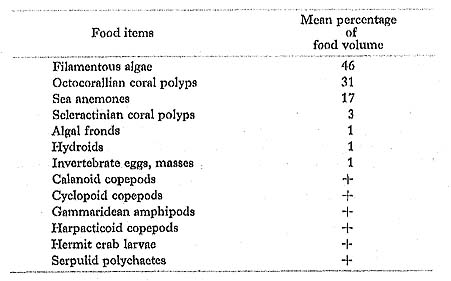

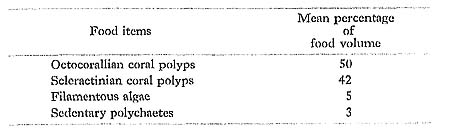

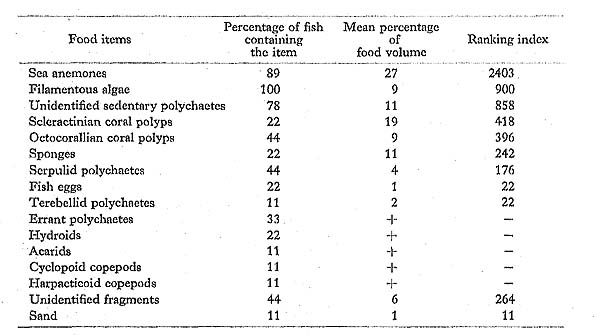

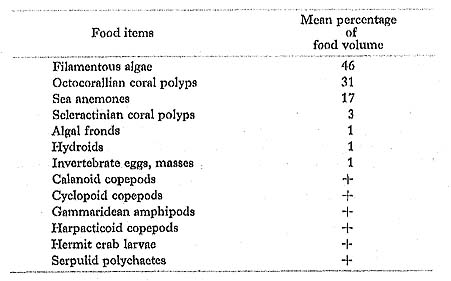

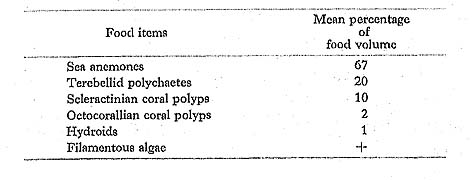

In addition to algae, C. kleinii had preyed heavily on anthozoans, especially octocoral lian corals and sea anemones, suggesting that this species at Minatogawa is strictly omnivorous. In contrast to these food data, Hobson (1974) reported that C, kleinii (as C. corallicola, see Burgess (1978: 39, 700)) in Hawaii is a planktivore which feeds largely on copepods.

Chaetodon lineolatus Cuvier: Nise-furai-chochouo

FUMT-P 4026, 4235; 6 specimens; spring and summer; 48-91 mm SL.

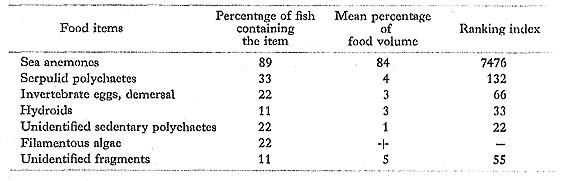

Most of the prey of C. lineolatus consisted of small sea anemones. Reese (1975) ob served this species at Heron Island browsing the surfaces of dead coral rocks, and thus presumed that it probably takes algae on the surfaces. However, we found the fact that C. lineolatus at Minatogawa scarcely feeds on algae.

Chaetodon lunula (Lacepède): Chohan

FUMT-P 4024, 4236; 9 specimens; spring and summer; 36-71 mm SL.

Although sea anemones were the major item in the diet of C. lunula at Minatogawa, Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) found only tips of coral polyps in the single C. lunula (135 mm SL) from the Marshall Islands, On the other hand, Hobson (1974) reported that C. lunula.in Hawaii is a nocturnal predator that preys on benthonic invertebrates, especially opisthobranchs, obtaining much of its food by habitually tearing off pieces of large ones.

Chaetodon melannotus Bloch et Schneider: Akcbono-chochouo

FUMT-P 4030, 4237; 2 specimens; spring and summer; 54 and 67 mm SL.

In feeding mostly on anthozoans, the diet of C. melannotus at Minatogawa was essen tially the same as that of the same species in Tutia Reef, off the Tanganyika coast (Talbot, 1965) and the Red Sea (Harmelin-Vivien and Bouchon-Navaro, 1981).

Chaetodon ornatissimus Cuvier: Hanaguro-chochouo

FUMT-P 4027.

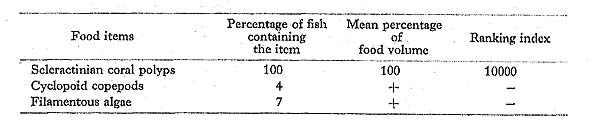

Two specimens (72 and 81 mm SL) were collected in summer, and the stomachs of both were full of scleractinian coral polyps, along with much mucus. Similar feeding has been noted in Hawaii by Hobson (1974), who suggested that C. ornatissimus obtains significant nourishment from coral mucus.

Chaetodon plebeius Cuvier; Sumitsuki-tonosamadai

FUMT-P 4028, 4238; 15 specimens; spring and summer; 39-74 mm SL.

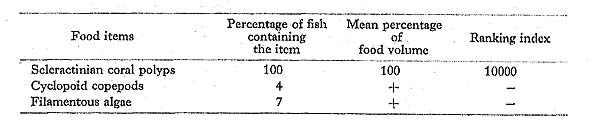

C. plebeius specimens had stomachs full of acleractinian coral polyps and mucus. On Minatogawa reefs, we observed it repeatedly picking the surfaces of living corals, mostly Acropora, as did Reese (1975) for the same species at Heron Island.

Chaetodon rafflesii Bennett: Ami-chochouo

FUMT-P 4239; 2 specimens; spring; 62 and 70 mm SL.

C. raffiesii had fed chiefly on sessile invertebrates, especially sea anemones.

Chaetodon speculum Cuvier: Tonosamadai

FUMT-P 4029, 4240; 4 specimens; spring and summer; 40-69 mm SL.

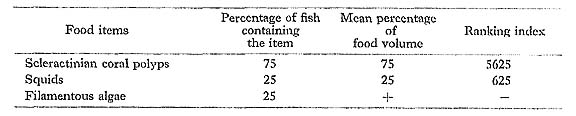

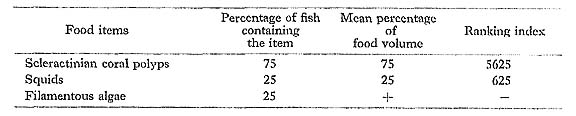

Three specimens among the four examined had stomachs full of only scleractinian coral polyps and mucus, whereas the other (69 m SL) was full of squids. Although we are unable to determine exactly the food habit of C. speculum at Minatogawa, we tcnta-tively label this species as a scleractinian coral polyp-feeder.

Chaetodon trifascialis Quoy et Gaimard: Yarikatagi

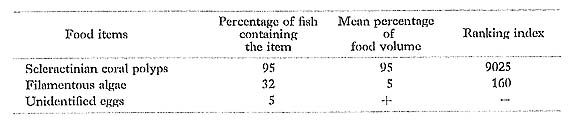

FUMT-P 4018, 4242; 23 specimens; spring and summer; 47-105 mm SL.

Scleractinian coral polyps and mucus, which predominated in the diet of C. trifascialis at Minatogawa, were also reported to be the major prey of the same species in the Mar shall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960; Reese, 1975: as Megaprotodon strigangulus), the Great Barrier Reef (Reese, 1975), and the Red Sea (Harmelin-Vivien and Bouchon-Navaro, 1981).

Chaetodon trifasciatus Mungo Park: Misuji-chochouo

FUMT-P 4019, 4243; 28 specimens; spring and summer; 43-100 mm SL.

Like C. trifascialis, almost all specimens of C. trifasciatus contained only scleractinian coral polyps and mucus with no skeletal material. We frequently observed it occurring in pairs on Minatogawa reefs and picking the surfaces of living corals, mostly Acropora. Talbot (1965) in Tutia Reef, off Tanganyika, and Reese (1975) also reported it to be a coral-feeding species.

Chaetodon ulietensis Cuvier: Sudare-chochouo

FUMT-P 4244.

A single young specimen (39 mm SL) was captured in spring. The major item in the diet was small sea anemones (percentage of food volume: 90%), and the remaining item was scleractinian coral polyps and mucus.

Chaetodon unimaculatus Bloch: Itten-chochouo

FUMT-P 3121.

Two specimens (96 and 117 mm SL) were collected in spring, and the stomachs of both were full of only scleractinian coral polyps and mucus with several skeletal frag ments.

There is controversy over the diet of C. unimaculatus. Talbot (1965) classified it in Tutia Reef, off Tanganyika, as a carnivore feeding on invertebrates other than corals. In contrast, Hobson (1974) found that the major prey of C. unimaculatus in Hawaii were scleractinian corals, mostly Pocillopora, including many skeletal fragments, which agrees well with our result at Minatogawa. On the other hand, Reese (1975) reported it to be an omnivore, but we found no evidence that it takes an algal diet.

Chaetodon vagabundus Linnaeus; Furai-chochouo

FUMT-P 4020, 4245; 10 specimens; spring and summer; 40-97 mm SL.

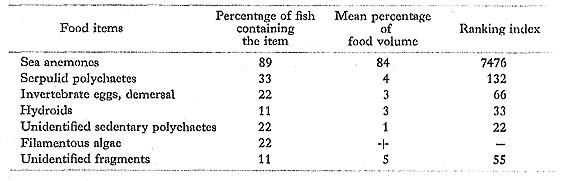

Although most of the prey of C, vagabundus at Minatogawa were sea anemones and sedentary polychaetes, Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) found only coral polyps and algae in this species from the Marshall Islands. On the other hand, Reese (1975) observed it at Heron Island picking the surfaces of coral rocks, presumably for algae and small inverte brates, but not on living corals. Although we detected both coral polyps and algae in the diet of C. vagabundus at Minatogawa, neither of them was contained in a large amount.

Heniochus chrysostomus Cuvier: Minami-hatatatedai

FUMT-P 4034.

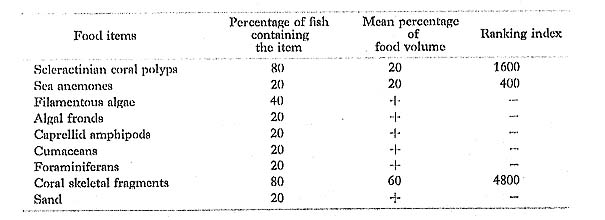

Three specimens (37-41 mm SL) were collected from areas of dense coral growth, especially staghorn Acropora, in summer. All of their stomachs were full of scleractinian coral polyps and mucus, along with very few fragments of algae (less than 1% of the content) that may have been taken incidentally.

Family Zanclidae: Tsunodashi-ka

Zanclus cornutus (Linnaeus): Tsunodashi

FUMT-P 4035, 4246; 30 specimens; spring and summer; 54-117 mm SL; 2 empty.

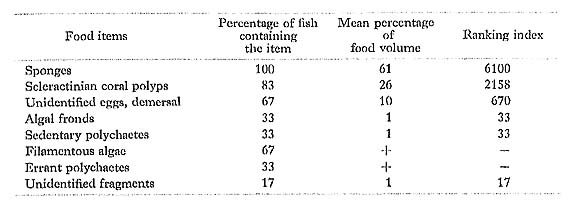

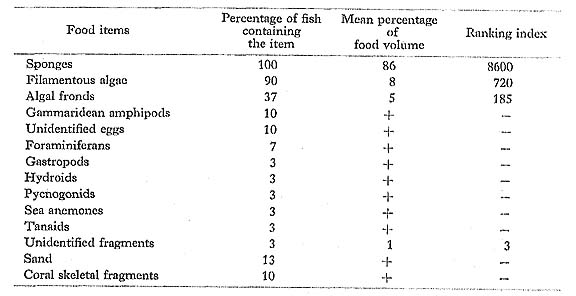

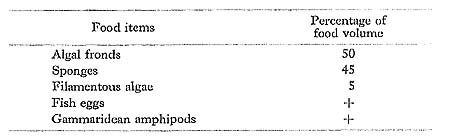

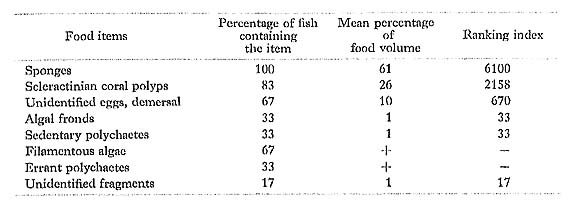

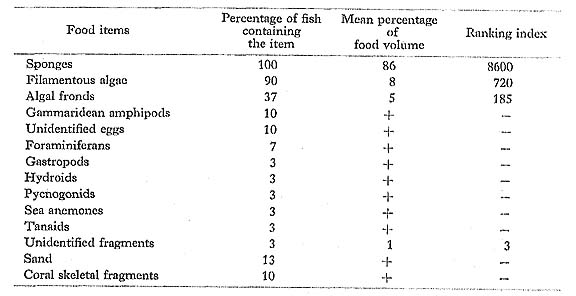

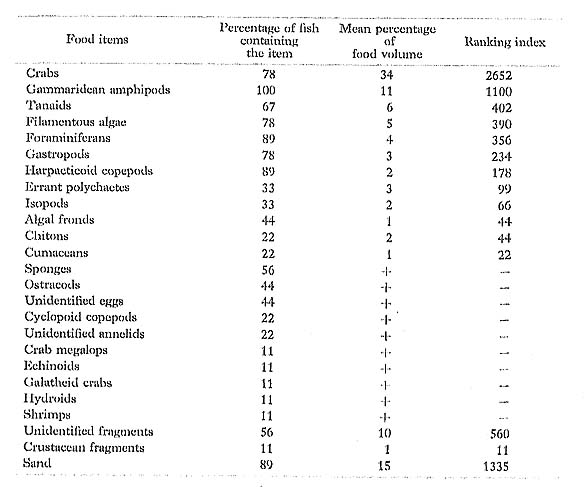

Z. cornutus had fed primarily on spónges and algae, as did the same species from Hawaii examined by Hobson (1974). In contrast to these food data, however, Randall (1955) found only algae with a small amount of bottom sediment in the two specimens that he examined in the Gilbert Islands.

Family Acanthuridae: Nizadai-ka

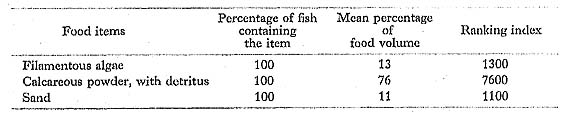

Acanthurus dussumieri Valenciennes: Nise-kanran-hagi

FUMT-P 4054, 4247; 11 specimens; spring and summer; 61-108 mm SL.

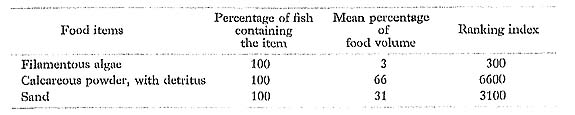

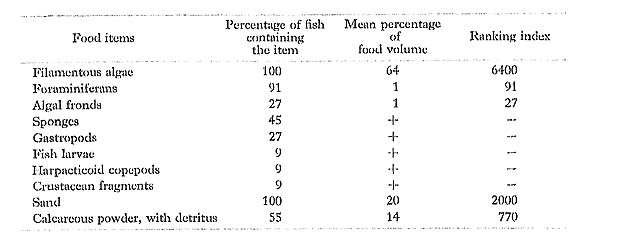

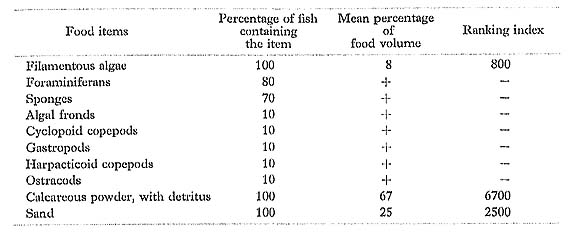

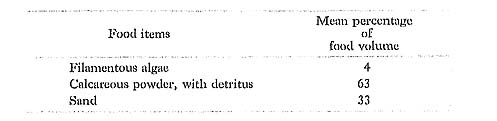

A. dussumieri contained largely filamentous algae and detritus, mixed with calcareous powder and sand in the stomach. Jones (1968) found sand, diatoms, and detritus with very few fragments of algae in the gut of this species in Hawaii and Johnston Island. But he. also recognized that A. dussunmieri from Diamond Head and Maunalua Bay, Oahu, contained large amounts of algae, especially the specimens from Diamond Head had no sand at all in the gut. Thus, he concluded that it is usually a grazer picking up mouthfuls of sand in sand patch areas, although it does not graze on occasion. Gushima (1981), on the other hand, found large quantities of algae (mean percentage of food volume; 92%) in the 40 specimens (100-330 mm TL) from Kuchierabu Island, Japan, whereas sand in the gut was of much smaller quantities (8%).

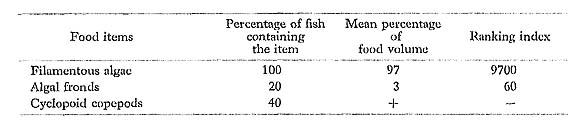

Acanthurus lineatus (Linnaeus): Niji-hagi

FUMT-P 4057; 4 specimens; summer; 51-77 mm SL.

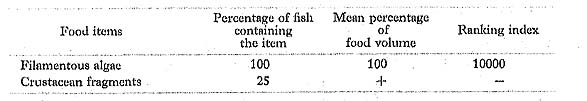

All specimens of A. lineatus collected from the surge zone of the seaward reef flat had stomachs full of filamentous algae, with no calcareous material or sand. These prey are much the same as those taken by the same species in the Gilbert Islands (Randall, 1955), the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960), and Aldabra Atoll, western Indian Ocean (Robertson and Polunin, 1981).

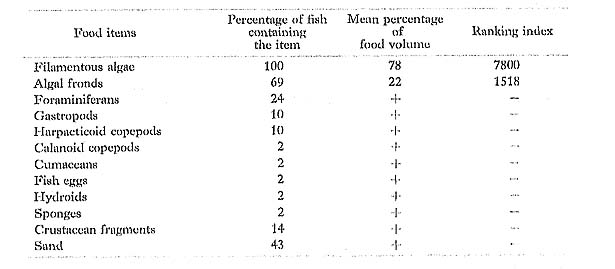

Acanthurus nigrofuscus (Forsskål): Naga-niza

FUMT-P 4053, 4248; 9 specimens; spring and summer; 71-133 mm SL.

In eating mainly algae with little or no calcareous material or sand, A. nigrofusms at Minatogawa had a diet similar to that of the same species in Hawaii and Johnston Island (Jones, 1968) and Kuchierabu Island, Japan (Gushima, 1981).

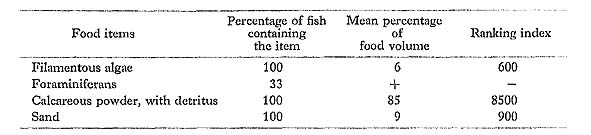

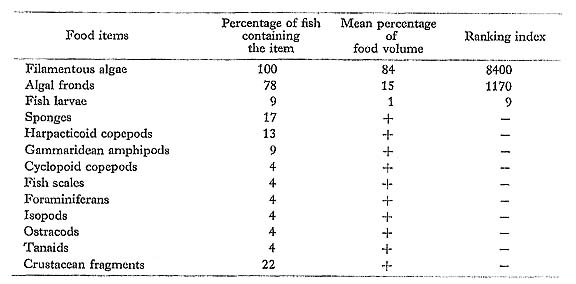

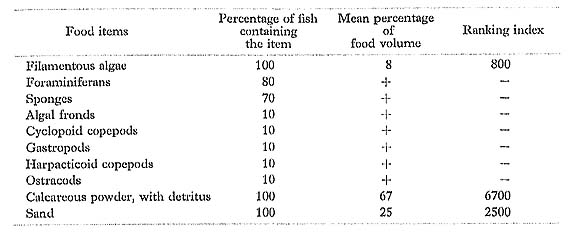

Acanthurus olivaceus Bloch et Schneider: Montsuki-hagi

FUMT-P 4058; 1 specimen; summer; 84 mm SL.

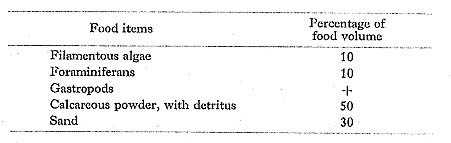

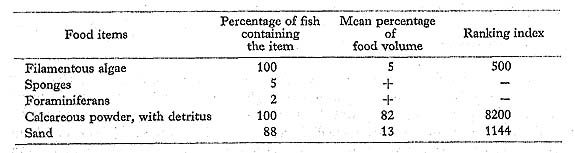

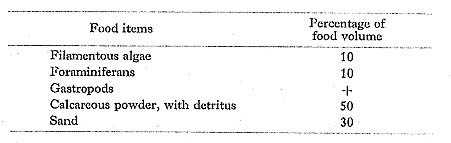

Filamentous algae and detritus mixed with calcareous powder and sand, which predominated in the diet of A. olivaceus at Minatogawa, were also reported to be major prey of the same species in the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960), Hawaii and Johnston Island (Jones, 1968), and Kuchierabu Island (Gushima, 1981). Probably, the foraminiferans and gastropods in the stomach were taken incidentally when the fish scraped algae, its major food, from the surfaces of dead corals or rocks.

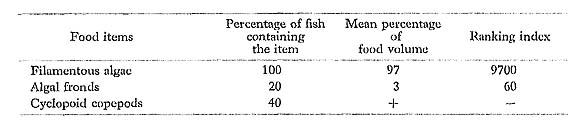

Acanthurus triostegus (Linnaeus): Shima-hagi

FUMT-P 4055.

Three specimens (53-68 mm SL) collected from the surge zone of the seaward reef flat in summer had taken only filamentous algae with no calcareous material or sand, which is much the same prey as taken by the same species in the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960) and Hawaii (Randall, 1961: as A. triostegns sandvicensis).

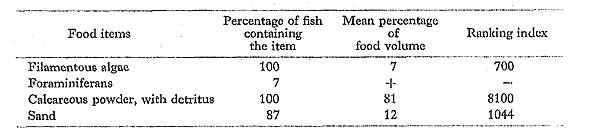

Ctenochaetus striatus (Quoy et Gaimard): Sazanami-hagi

FUMT-P 4052, 4249; 10 specimens; spring and summer; 48-143 mm SL.

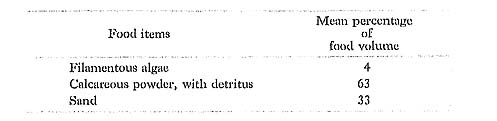

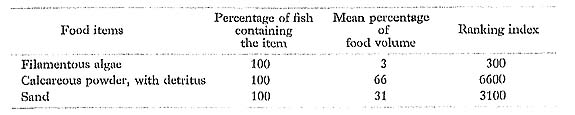

In feeding mostly on filamentous algae and detritus mixed with large amounts of calcareous powder and sand, the diet of C. striatus at Minatogawa was essentially the same as that of the same species in the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960) and Hawaii and Johnston Island (Jones, 1968).

Naso sp.

FUMT-P 4059, 4250; 5 specimens; spring and summer; 48-71 mm SL.

All the specimens of Naso sp. examined were young, and their prey was mostly algae, with little or no calcareous material or sand.

Jones (1968) examined the feeding habits for the following four species of the genus Naso in Hawaii and Johnston Island: N. brevirostris, N. lituratus, N. micornis, and N. hexacanthus. As a result, he found the former three species to be browsing herbivores, whereas the other is a zooplankton-feeder which takes mostly copepods, crab zoea, crab megalops, and mysids. Hobson (1974) also stated that "N, hexacanthus in Hawaii is a diurnal planktivore that takes mostly semitransparent, often gelatinous, prey-especially chaetognaths, larvaceans, and fish eggs."

Zebrasoma flavescens (Bennett): Kiiro-hagi

FUMT-P 4251.

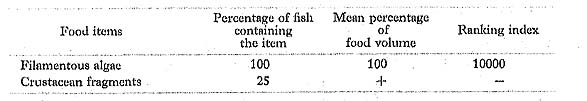

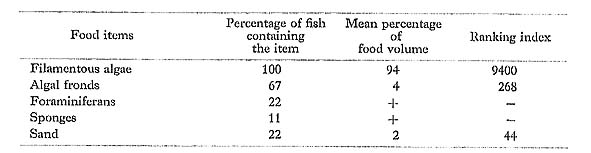

A single specimen (60 mm SL) collected in spring contained only filamentous algae (percentage of food volume: 95%) and algal fronds (5%), with no sand or calcareous

powder mixed in. Jones (1968) similarly reported it in Hawaii and Johnston Island to be a browsing herbivore.

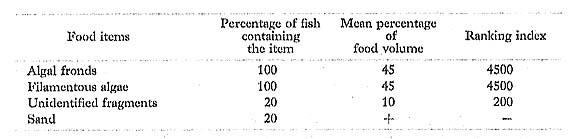

Zebrasoma scopas (Cuvier): Goma-hagi

FUMT-P 4252; 5 specimens; spring; 56-67 mm SL.

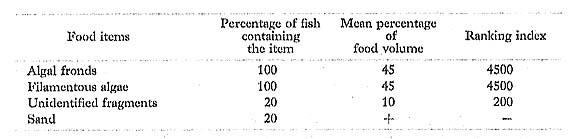

Z. scopas had fed predominantly on algae, with no sand or calcareous powder mixed.Robertson et al, (1979) examined the stomach contents of the 31 adult specimens of this species from Aldabra Atoll, western Indian Ocean, and found their prey to be small, soft benthonic algae-both filiform and filamentous.

Zebrasoma veliferum (Bloch); Hirenaga-hagi

FUMT-4056, 4253.

Eight, specimens (21-61 mm SL) were collected in spring and summer, and their stomachs were full of only filamentous algae, with no sand or calcareous powder. This result fits closely with those for the same species obtained by Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) in the Marshall Islands and Jones (1968) in Hawaii and Johnston Island.

Family Siganidae: Aigo-ka

Siganids at Minatogawa most often occur in small to large mixed schools with acarids and/or acanthurids on the coral reefs or seaward reef flats.

Siganus chrysospilos (Bleeker): Buchi-aigo

FUMT-P 4062, 4226; 6 specimens; spring and summer; 56-93 mm SL.

In addition to sponges, S. chrysospilos had fed heavily on algae.

Siganus covallinus (Valenciennes): Sango-aigo

FUMT-P 4063.

A single specimen (58 mm SL) was collected in summer, and its stomach was full of only algae, both filaments (percentage of food volume: 60%) and fronds (40%).

Siganus rostratus (Valenciennes): Hana-aigo

FUMT-P 4179.

Only algae, both fronds (percentage of food volume: 70%) and filaments (30%), were taken as food in the single specimen (275 mm SL) collected in summer.

Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) described this species in the Marshall Islands as a browsing herbivore.

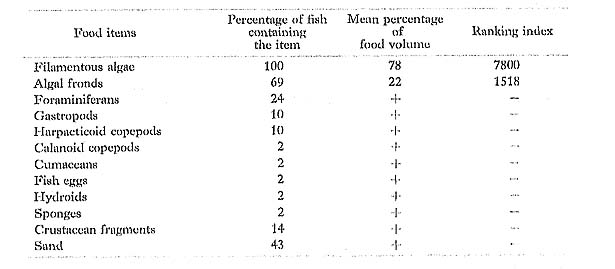

Siganus spinus (Linnaeus): Ami-aigo

FUMT-P 4060, 4227; 42 specimens; spring and summer; 48-101 mm SL.

S. spinus, which was the most numeroua umong the congeners on Minatogawa recfs, fed predominantly on algae, both filaments and fronds. Gushima (1981) similarly reported that small algae, including mostly green and red algae, constituted the major food (mean percentage of food volume: 99%) of this species at Kuchierabu Island. The various animal-food items in the stomachs probably were taken incidentally when the fish bit off pieces of algae growing on dead corals or rocks.

Siganus virgatus (Valenciennes): Hime-aigo

FUMT-P 4061, 4228; 23 specimens; spring and summer; 30-87 mm SL.

Most of the prey of S. virgatus were algae, both filaments and fronds. The various animal-food items in the stomachs probably were taken inadvertently.

Family Balistidae: Mongarakawahagi-ka

Balistapus aculeatus (Linnaeus): Murasame-mongara

FUMT-P 4170, 4324; 9 specimens; spring and summer; 80-161 mm SL.

B. aculeatus had taken various small benthonic invertebrates and algae. Although Hiatt and Btraaburg (1960) found similar prey in the same species (as Rhinecanthus aculeatus) from the Marshall Islands, they also found a great number of broken off Acrupora coral tips in the single specimen. We found no evidence that this species at Minatogawa takes scleractinian corals.

Balistapus echarpe (Anonymous): Tasuki-mongara

FUMT-P 4171; 2 specimens; summer; 93 and 102 mm SL.

In feeding mostly on small crustaceans and algae, the diet of B. echarpe at Minatogawa was essentially the same as that of the same species in the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960: as Rhinecanthus rectangulus) and Hawaii (Hobson, 1974: as R, rectangulus).

Balistes flavimarginatus Rüppell: Kiheri-mongara

FUMT-P 4325; 1 specimen; spring; 107 mm SL.

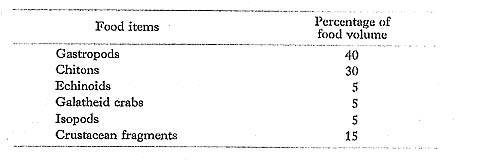

In contrast to the omnivorous B. aculeatus and B. echarpe, this species appears to be strictly carnivorous. Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) also found crustaceans, gastropods, foraminiferans, and tunicates in the two specimens (190 and 460 mm SL) from the Marshall Islands.

Family Monacanthidae: Kawahagi-ka

Oxymonacanthus longirostris (Bloch et Schneider): Tengu-kawahagi

FUMT-P 4172, 4326; 19 specimens; spring and summer; 48-68 mm SL; 1 empty.

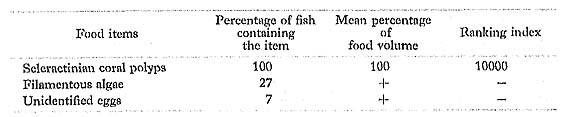

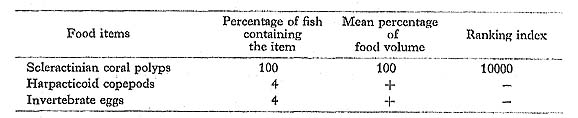

O. longirostris had taken chiefly sclcractinian coral polyps along with much mucus. We observed it repeatedly picking the surfaces of living corals, mostly Acropora. Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) also found only bitten off coral polyps with no skeletal material in the two specimens (both 75 mm SL) that they examined in the Marshall Islands. In addition to these food data, Hobson (1975) noted that the protruding snout and teeth projecting from small mouth of this species are well suited to snipping off sclcractinian coral polyps surrounding calcareous armor. The filamentous algae and eggs among its gut contents probably were taken incidentally along with its major prey.

Family Tetraodontidae; Fugu-ka

Tetraodon nigropunctatus (Bloch et Schneider): Kokutcn-fugu

FUMT-P 4173, 4327; 5 specimens; spring and summer; 134-264 mm SL; 1 empty.

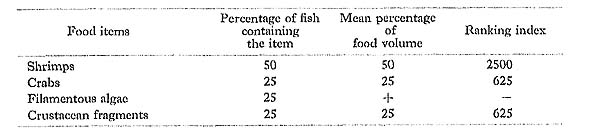

Four specimens among the five examined predominantly contained living tips of Acropora corals in the gut, whereas the other (134 mm, SL) was full of mostly sea anemones with no evident trace of living corals. Except for the sea anemones, the diet of this species at Minatogawa was much the same as that of the same species in the Gilbert Islands (Randall, 1955: as Arothron nigropunctatus) and the Marshall Islands (Hiatt and Strasburg, 1960). These food data suggest that this species is at least dominantly a

coral feeder which breaks off living coral tips with its fused, beak-like teeth, although it may also take other prey on occasion.

Family Diodontidae: Harisenbon-ka

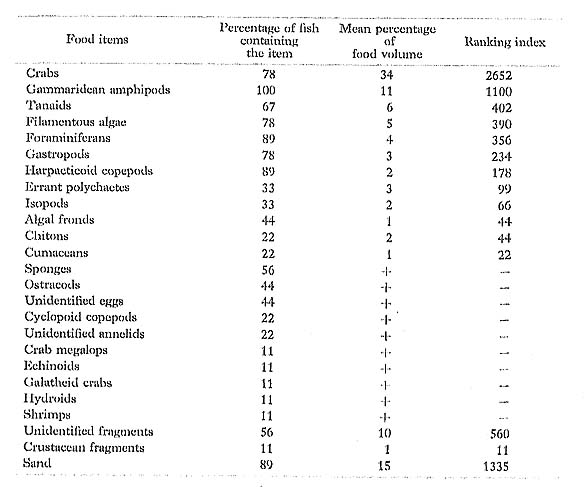

Diodon liturosus Shaw: Hitozura-harisenbon

FUMT-P 4174, 4328; 6 specimens; spring and summer; 108-271 mm SL.

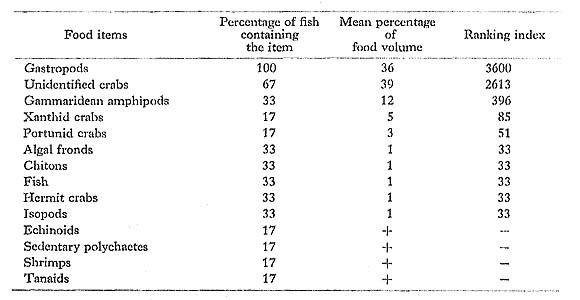

D. liturosus had fed mostly on benthonic invertebrates, especially crabs and gastropods, both of which had been crushed by its fused, beak-like teeth and strong jaws. Because this species secretes itself between branches of corals or within reef caves or crevices at Minatogawa during the day, presumably it is a nocturnal predator, like two congeners, D, holocanthus and D. hystrix (Hobson, 1974).

Family Scorpaenidae: Fusahasago-ka

Dendrochirus zebra (Quoy et Gaimard); Kirinmino

FUMT-P 4329.

A single specimen (68 mm SL) collected in spring contained shrimps (percentage of food volume: 80%), crabs (10%), and isopods (10%) in the stomach.

Harmelin-Vivien and Bouchon (1976) found crabs (percentage of food weight: 82%), shrimps (17%), and amphipods (1%) in the single D. zebra from Tulear, Madagascar.

Pterois volitans (Linnaeus): Hana-mino-kasago

FUMT-P 4175.

The major food item of the single specimen (72 mm SL) collected in summer was small fishes (percentage of food volume: 95%), and the remaining item was portunid crabs.

Hiatt and Strasburg (1960) found a shrimp, Stenopus hispidus, in the single specimen (230 mm SL) that they examined in the Marshall Islands. Harmelin-Vivien and Bouchon (1976) reported fishes and crustaceans, especially crabs, in the diet of P. volitans from Tuléar, Madagascar.

Scorpaenodes kelloggi (Jenkins): Gwamu-kasago

FUMT-P 4176, 4339; 4 specimens; spring and summer; 41-58 mm SL; 2 empty.

Most of the prey of S. kelloggi were benthonic decapods.

Family Soleidae: Sasaushinoshita-ka

Pardachirus pavoninus (Lacepède); Minami-ushinoshita

FUMT-P 4331.

Only errant polychaetes were taken as food in the single specimen (158 mm SL) collected from a shallow sandy area in spring.