CHAPTER 15

The Animal Bones from the 1974 Excavations at Douara Cave

Sebastian Payne

Trinity Collage, University of Cambridge

| ( 4 / 10 ) |

|

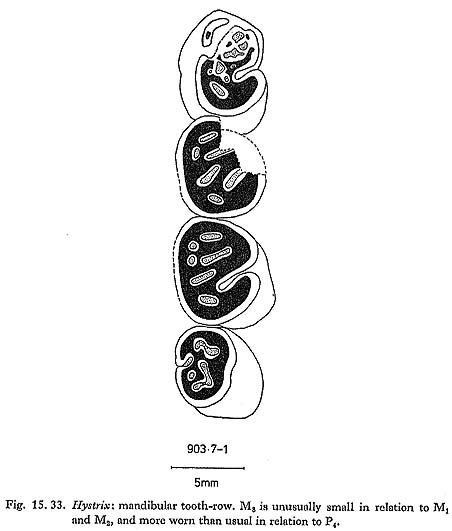

Hystricidae 15.2.3.18 Hystrix sp. (Fig. 15. 33)

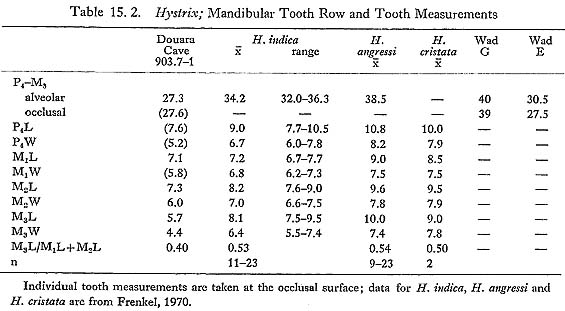

One mandible (903.7-1), two broken incisors (903.11-6 and 1011.6-1) and an incisor fragment (808. 8-8) were found; the mandibular tooth row is illustrated (Fig. 15. 33), and measurements are given in Table 15. 2.

Hystrix indica, is the only porcupine to occur today in the Near East; it is replaced in North Africa by H. cristata, which is widespread throughout Africa, and is also found in Sicily and southern Italy (Corbet and Jones, 1965). A large fossil species, H. angressi, has been described from a Levalloiso-Mousterian site in Israel (Frenkel, 1970). The Douara Cave mandible differs from these in three ways: it is smaller (Table 15. 2); M3 is relatively reduced (Table 15.2: M3L/M1L+M2L); and wear is advanced on M3 in relation to P4, suggesting that P4 may have erupted later than usual (compare Frenkel, 1970: Plate III. 12 and 17-20). Larger porcupine remains are known from a number of sites on the Levant coast (e.g. Ksar'Akil, and Kebara: Frenkel, 1970), and can probably be referred to H. angressi. A mandible from Wad G is of similarly large size (Table 15. 2), but another from Wad E is very much smaller. Bate's comment that the two "appear to differ so considerably that the presence of two species is suggested" (Bate, 1937: 185) seems entirely reasonable, in view of the relatively low variability shown by modern H. indica (Table 15. 2). If the Wad E mandible is Hystrix indica, this species has increased considerably in size since that date-perhaps, it might be suggested, as a consequence of the extinction of H. angressi, The Douara Cave mandible is slightly smaller than the Wad E mandible, and differs from it in the reduction of M3, which is the same size as M1 and M2 in the Wad E mandible. This difference may simply reflect individual variation; another possibility is that the Palmyra Oasis supported an isolated population of porcupines with reduced third molars; and another possibility is that a third species of Hystrix is present. In default of more material, the question must be left open, and a specific identification is not suggested. H.indica is widely distributed in the Near East, but does not penetrate into the great deserts of the interior. CARNIVORA Canidae 15.2.3.19 Canis sp. (Plates 15.1-4; Figs. 15. 34-36)

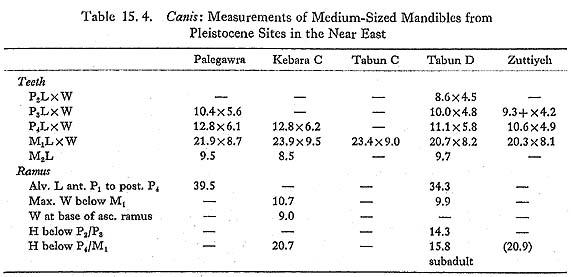

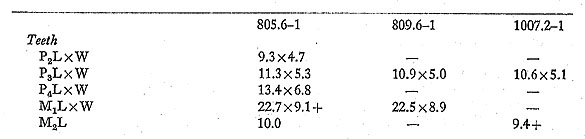

A number of medium-sized canid bones were found, including three mandibles, each from a different individual. Measurements of these are as follows:

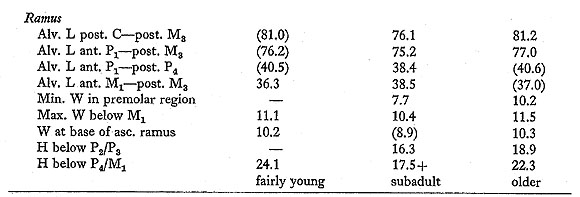

Tooth lengths taken as crown maxima: not necessarily in axis of tooth row. 805.6-1(Plate 15. 1) is a fairly complete left mandible from. a young animal: teeth are fully erupted, and dentine is exposed by wear only on some cusp tips. P4 is large and strong, with two well-marked small cusps on the posterior cutting edge and a tiny posterior singular cusplet. M1 is stout, with a small metaconid; the talonid is reduced, with the hypoconid clearly larger than the entoconid, and with no accessory cusplets. M2 has low cusps; the postero-internal corner is occupied by a low, flat area, with a very slight ridge on the internal edge but no trace of a cusp or cusplet. The mandible is robust and strikingly deep; the diastema between the canine and the first premolar is ca. 4.8 mm, and there is a smaller gap between P2 and P3. The tooth row is slightly curved, without any crowding: the extent of overlap between P4 and M1 is normal in both wolves and jackals. 809.6-1,which is the anterior part of a right mandibular ramus, joins 906(30-100)-2, which is the posterior part of the ramus; 810.10D-1, an unworn M1, clearly fits into the mandible, and 809. 7-1, a premolar, appears to fit into the P3 alveoli. The different units in which these specimens were found are some distance apart: 906(30-100)-2 comes from a collapse of the upper part of the section (equivalent to 9-06. 1 to .7) in square 9-06, at least two meters from 8-09, in which the anterior ramus was found; the premolar is from the unit directly below the anterior ramus, and the first molar is from an adjacent square, more than 30 cm deeper. The break between the two parts of the ramus is not a recent break, and there is slight concretion at points on the broken surface; all the alveoli are equally stained. The mandible was evidently broken and its parts dispersed during the accumulation of the deposits within which it was found. 809. 6-1 (Plates 15. 1-2) was subadult: neither of the teeth shows any trace of wear, and M3 was only very recently erupted: the bone around M3 is markedly porous, and the alveolus is set into the upward curve of the ascending ramus above the level of the rest of the tooth row. M1 is similar to that of 805. 6-1, except that the metaconid is stronger, and there is slight development of the posterior cingulum. The mandible is strikingly shallow, in contrast to 805. 6-1, and there is virtually no diastema between the canine and the first premolar. The tooth row is slightly curved, and there is some slight crowding of the premolars, as is to be expected in subadults. 1007. 2-1 (Plate 15. 3) was older; most of the teeth are missing, but P3 and M2 are present, and Ma is moderately worn. M2 again lacks any postero-internal cusp. The mandible is moderately deep, and strongly built in the premolar region. The diastema between the canine and the first premolar is ca. 4.2 mm, and there is a small gap between P2 and P3. The tooth row is slightly curved, and there is no crowding of the premolars. Postcranial measurements are as follows:

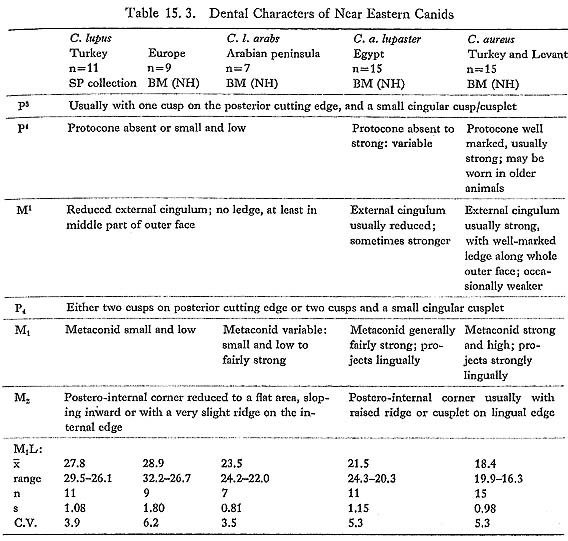

That the mandibles are Canis and not Cuon is clear: all three have M3 alveoli (M3 is lacking in Upper Pleistocene and recent Cuon), and each of the two preserved first molars has a well-developed entoconid and hypoconid (the talonid in Cuon is reduced to a single trenchant cusp). The specific identification of Canis from Near Eastern sites is far from easy; most of the characters that have been used are subject to considerable intraspecific variation. Two extant wild species are usually recognized: Canis lupus, the wolf, usually held to be the sole ancestor of domestic dogs, and C. aureus, the golden jackal. The taxonomic situation is complicated, however, by the existence of rather distinct subspecies within both species. C. lupus in Europe, Turkey and the Zagros is large, with a gradual size decrease eastward into India (C. l. pallipes). Wolves in the Arabian Peninsula (C. l. arabs) are considerably smaller, and overlap in size with the Egyptian jackal, C. a. lupaster (also known as the wolf-jackal); while jackals in the Levant, Turkey and southeastern Europe are smaller again. In dental morphology (the main source of evidence for the identification of fossil mate- rial), Turkish C. lupus and C. aureus are clearly distinct, while C. l. arabs and C. a. lupaster are to some extent intermediate: dental characteristics are summarized in Table 15. 3. C. l. arabs, though much smaller, is morphologically close to Turkish C. lupus; the rnetaconid in M1 is sometimes rather larger in the material seen. C. a. lupaster differs from Turkish and Levantine C. aureus in the more frequent reduction of the protocone in P4, and in the reduction of the external cingulum in M1 (usually regarded as a good character separating C. lupus from C. aureus). In general terms these differences can be seen as a trend toward a more specialized heavy and sectorial dentition in C.lupus, as compared with the more generalized dentition of C. aureus; C.l. arabs is fairly close to the other C. lupus subspecies, while C. a.lupaster occupies the middle ground. This trend may to some extent be related to size, but it should be noted that C. l. arabs and C. a. lupaster are similar in size, but differ in dental morphology.

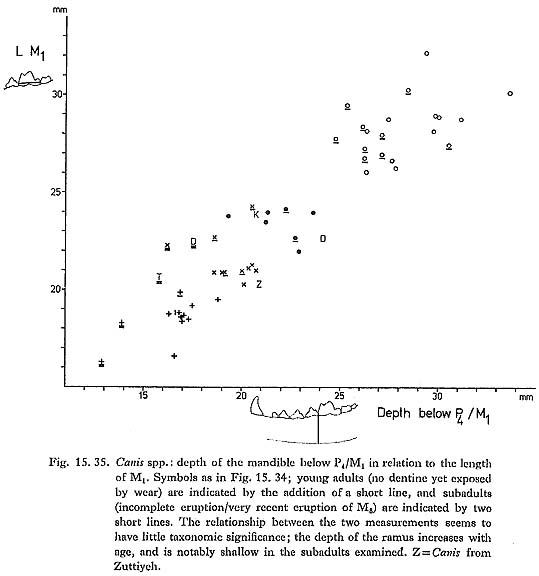

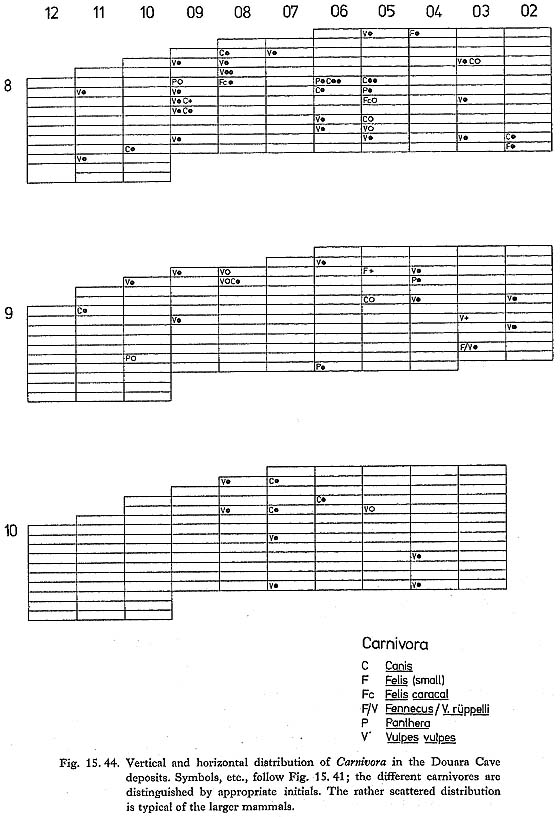

Turning to the Pleistocene fossil record in the Near East, Kurtén (1965), in a general study of carnivores from the Palestine caves, concludes that two Canis species are represented through the Upper Pleistocene in the Levant: C. lupus, which is as large as European C. lupus, until it decreases dramatically in size at the end of the last glaciation to become modern C. l. arabs; and C. lupaster, which he regards as specifically distinct from C. aureus. C. aureus itself was only identified from surface levels at Ksar'Akil. The Douara Cave canids are not easy to accommodate within this framework: they are very much smaller than the large Pleistocene C. lupus from the Palestine caves and from Ksar'Akil (Hooijer, 1961), and yet morphologically they resemble C. lupus more closely than either C. aureus or C. a. lupaster. As Fig. 15. 34 shows, one feature in which C. l. arabs consistently differs from C. a. lupaster is the relative lengths of P4 and M2, and the Douara Cave canid clearly resembles C. l. arabs in this respect. The somewhat stronger metaconid in the first molar (810. 10D-1) that fits 809. 6-1 would be unusual in Turkish C. lupus, but is not out of place in C. l. arabs. The only feature that might be thought to be jackal like in any of the Douara Cave canids is the shallowness of the mandibular ramus in 809. 6-1, but, as Fig. 15. 35 shows, the depth of the mandibular ramus relative to the length of M1 has little taxonomic significance in the samples examined, but shows considerable variation in relation to the age of the individual; subadults generally have shallow rami, and 809. 6-1 is a subadult. Before concluding that the Douara Cave canid is a Mousterian C. l. arabs, two other possibilities have to be considered. First, is it possible that the specimens might be intrusive? This seems highly improbable: as Figs. 15. 44 and .5 show, the majority of the Canis specimens are from units below any evidence of post-Mousterian contamination, which, taken together with the fact that at least three individuals are represented, and that their condition is similar to the rest of the animal bones from the same units, strongly suggests that the Canis remains are not intrusive. Nonetheless, a direct test is desirable; samples have been submitted for ESR and racemization dating, and it is hoped that a radiocarbon dating may shortly be possible.

Second, is it possible that the Douara Cave canid might be a domestic dog? While this is not impossible, even given the very early date of the Mousterian occupation, and while a very similar mandible from the Zarzian (ca. 12,000 B.C.) site of Palegawra in Iraq has been identified as dog (Turnbull and Reed, 1974), there is nothing that of itself suggests that the Douara Cave canids were domestic. There is nothing in the circumstances in which they were found to suggest special treatment, no pathology or abnormality that might relate to domestication, no disproportion between the teeth and the mandible, and no crowding of the teeth-except in 809. 6-1, which is subadult (and crowding is normal in subadult wild canids). The same is in fact true of the Palegawra canid: the case for its identification as a domestic dog rests largely on its small size, as compared with modern Zagros C. lupus, and its clear similarity in dental morphology to C. lupus, rather than to C. aureus. Turnbull and Reed draw attention to features of the Palegawra mandible, such as the shallowness of the canine alveolus, the short diastema between the canine and the first premolar, the shortness of the premolar row, and the overlap between P4 and M1;but in none of these characters does the Palegawra mandible seem clearly to differ from C.l.arabs, which is not considered. The length of the diastema is highly variable within populations: in a sample of 11 Turkish C. lupus, it varies from 3.1 mm to 8.0 mm ( If the Douara Cave and Palegawra canids are identified as C. l. arabs, what relationship did they have to the very large C. lupus present in the Palestine caves and at Ksar'Akil? The Douara Cave specimens are so much smaller than the large coastal C. lupus (average M1 length 28.2 mm [Kurtén, 1965], as compared with 22.7 and 22.5 mm for the Douara Cave canids; assuming normal variability for M1 length as in modern canid samples, the Douara Cave canids are about 4 to 5 standard deviations smaller than the coastal C. lupus) that it is difficult to see both as part of the same breeding population, given the mobility of wolves, the relatively small distances involved, and the lack of any major physical barrier. One possible explanation is that the two are not contemporary, and that, just as Kurtén suggests that there was a dramatic size decrease at the end of the last glaciation, the Douara Cave canid may represent an earlier period of size decrease, perhaps during the last interglacial. This explanation is not without difficulties, however, especially as European C. lupus has remained fairly stable in size over the same time period (Suire, 1969). An alternative possibility is to question whether the large C. lupus of the Palestine caves did in fact, as Kurtén suggested, give rise to C. l. arabs; and instead to suggest that C. l. arabs may be a long-established population, adapted to desert and semi-desert conditions in contrast to the forest-adapted C. lupus, and characterized by smaller size and a less specialized dentition. Indeed, the difference is large enough and of long enough standing to justify considering whether C. l. arabs should be recognized as a separate species. If so, the Douara Cave and Palegawra canids would both be attributable to this population, as also would other similar specimens, such as a mandible from Kebara C and a lower carnassial from Tabun C (Table 15. 4). It may be significant in this context that all these specimens come from contexts with relatively dry indications, while there are no similar specimens from Ksar'Akil, with its consistently wetter and more wooded surroundings. The Tabun C specimen was identified as C. lupaster by Bate (1937); the Kebara C specimen was identified as Canis sp. by Bate (Garrod, 1954), and as C. lupus by Kurtén (1965), and is clearly similar to the Douara Cave and Palegawra canids in size, in the relationship between the lengths of P4 and M2, and in such dental features as the weak development of the postero-internal corner of M2. Not all specimens identified in the past as C. lupaster are of this type; a pair of mandibles from Tabun D stands in clear contrast (Table 15. 4), as does a mandible from Zuttiyeh: both are smaller, and in the Tabun D specimen the relationship between the lengths of P4 and M2 is as in modern C. lupaster (Fig. 15. 34), and M2 has a postero-internal cusplet.

If this suggestion is correct, the apparent size reduction in C. lupus from the large Pleistocene form to modern C. l. arabs is interpreted instead as a replacement of one population by another. The suggestions made here also have implications for the ancestry of domestic dogs, but discussion of this question is not relevant to the purpose of this report. |

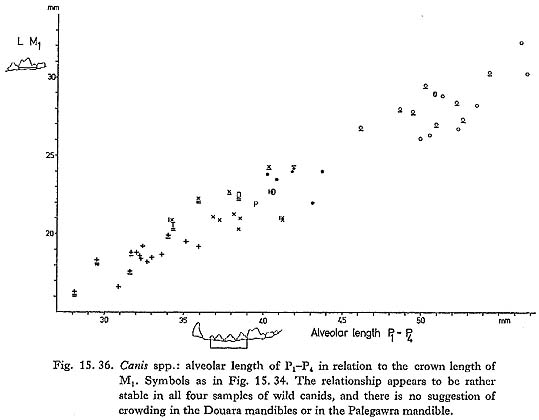

=5.5, s=1.9), with a coefficient of variation (C.V.) of 35! The premolars do not seem to be particularly crowded in the Palegawra mandible, nor does P4 seem to overlap M1 to any unusual extent (Turnbull and Reed, 1974: Plates III and IV): Fig. 15. 36 shows that the relationship between the alveolar length of the pfemolar row and the length of M1 is fairly constant in all the four samples of wild canids studied, and that the Palegawra and Douara Cave mandibles do not stand out in any way.

=5.5, s=1.9), with a coefficient of variation (C.V.) of 35! The premolars do not seem to be particularly crowded in the Palegawra mandible, nor does P4 seem to overlap M1 to any unusual extent (Turnbull and Reed, 1974: Plates III and IV): Fig. 15. 36 shows that the relationship between the alveolar length of the pfemolar row and the length of M1 is fairly constant in all the four samples of wild canids studied, and that the Palegawra and Douara Cave mandibles do not stand out in any way.