CHAPTER 15

The Animal Bones from the 1974 Excavations at Douara Cave

Sebastian Payne

Trinity Collage, University of Cambridge

| ( 2 / 10 ) |

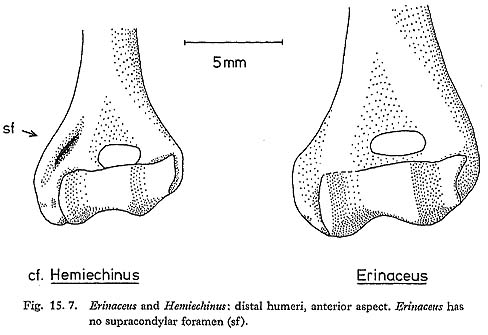

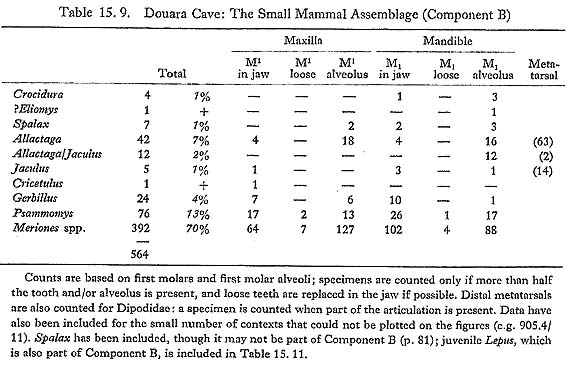

15.2 IDENTIFICATIONThe following section discusses the identification of the Douara Cave fauna and relevant taxonomic questions. Analysis and interpretation are left to the next section. 15.2.1 Problems of identificationUpper Pleistocene faunas present a general problem in identification: they are so close to modern faunas that it is all too tempting to force the fossil data into the modern mold, and thus to reinforce this resemblance-by identifying specimens that could equally belong to several species on morphological grounds to a single species on the basis of modern distributional probability, by assuming a modern taxonomic framework, and by ignoring the possible presence of extinct taxa whenever possible. All of this is reasonable enough on a "simplest hypothesis" basis, but we should be ready to consider alternative possibilities and to present our data in a way that is justified by the available evidence. A related problem is that identification is rarely as definite and exact as it is often made to appear. Individual morphological and metrical variation, in combination with agerelated and sexual differences, is often greater than is realized, and distinctions between closely related species are often far from clear-cut. Identification to species level is usually possible only with large samples, and only when the osteology of the genus concerned has been well studied. Meriones can be taken as an example. Taxonomic agreement on this genus is far from complete; Harrison (1972) recognizes seven species in the Near East, whose differentiation rests on pelage characteristics, skull proportions and the development and structure of the auditory bulla, none of which normally survive in archeological material. Dental characters are not used taxonomically, as dentition appears not to vary much within the genus. Despite this, Meriones mandibles and teeth from archeological sites are often identified to species level, apparently on little more basis than modern distribution; this identification may result in satisfying lists of binomials, but it does little to advance our knowledge of the history of the genus. As a consequence of an awareness of these problems, the identifications that follow are rarely taken below genus level; criteria are described and illustrated when possible; and in order to facilitate comparison with samples from other sites, as many specimens are measured and illustrated as possible. 15.2.2 MethodsSpecimens are numbered according to the unit in which they were found: thus specimens from unit 8-05.2 are numbered 805.2-1, 805.2-2, etc. Measurements are given in millimeters. Where precise measurement was not possible, + indicates that the value given is up to 2% too small (specimen slightly chipped or eroded); -indicates that the value given is up to 2% too large (specimen with an open crack); parentheses indicate that the value is correct within ± 2%; and ca. indicates a measurement that is still more approximate. Measurements taken on damaged or burnt specimens have been excluded from calculations of means and sample variability. Larger measurements were taken with slide callipers, and are given to the nearest 0.1 mm; smaller measurements, mostly of rodent teeth, were taken with a traveling microscope, and are given to the nearest 0.02 mm. Most of the measurements are defined by von den Driesch (1976),and her system of abbreviations is used; other measurements are defined when used. Drawings of the rodent teeth and other small specimens were made using a camera lucida attachment to a binocular microscope. 15.2.3 MammaliaINSECTIVORA Erinaceidae 15.2.3.1 cf. Hemiechinus sp. (Fig. 15. 7)

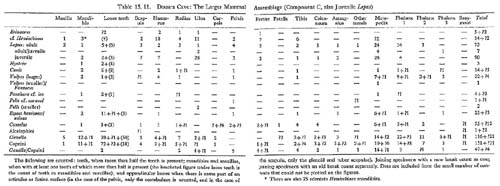

Two species of hedgehog are represented in the Douara Cave animal bones: a smaller species, which is common; and a larger species, which is relatively scarce (Table 15. 11).

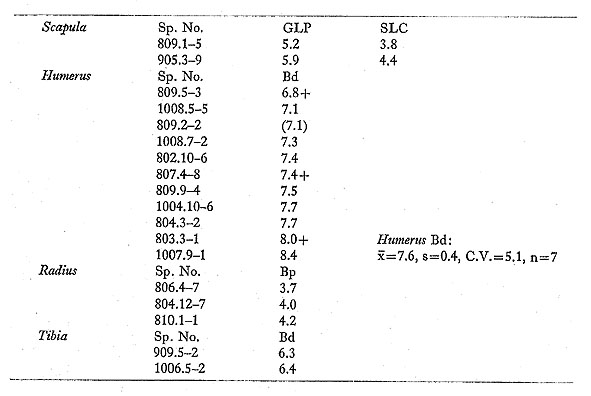

Distal humeri of the smaller species are fairly common; all of them have supracondylar foramina (Fig. 15. 7). Nearly all the mandibles are edentate; three preserve unerupted or partly-erupted P4 crowns, and these appear to be relatively short, and to have no internal metaconid. (This cannot be stated with complete certainty, as the crowns of these teeth are not fully formed.) These features suggest either Hemiechinus or Paraechinus, but exclude Erinaceus. The material compares closely with Hemiechinus, and differs slightly from the only Paraechinus skeleton seen; it is tentatively referred to Hemiechinus on this basis. Measurements are as follows:

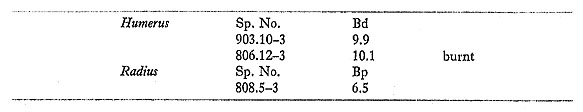

Hemiechinus auritus lives in semi-arid areas of the Near East, occupying a buffer zone between Erinaceus and the strictly desert-dwelling Paraechinus, and overlapping with both. It has been reported from a few Near Eastern cave sites: e.g. at Mount Carmel, where it was reported as Erinaceus cf. auritus (Bate, 1937), and at Palegawra (Turnbull and Reed, 1974). 15.2.3.2 Erinaceus sp. (Fig. 15. 7) The distal humeri of the larger species of hedgehog have no supracondylar foramen (Fig. 15. 7) and on this basis can be identified as Erinaceus. Measurements are as follows:

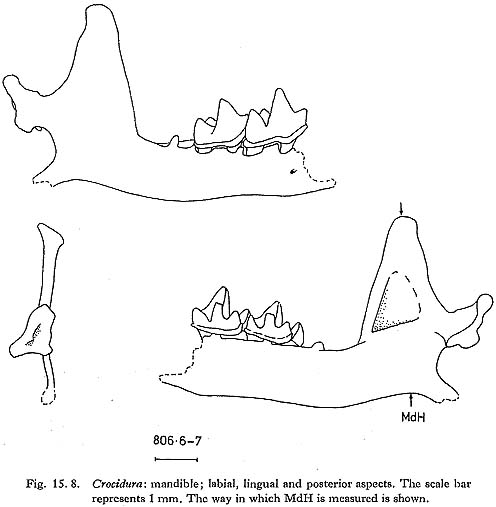

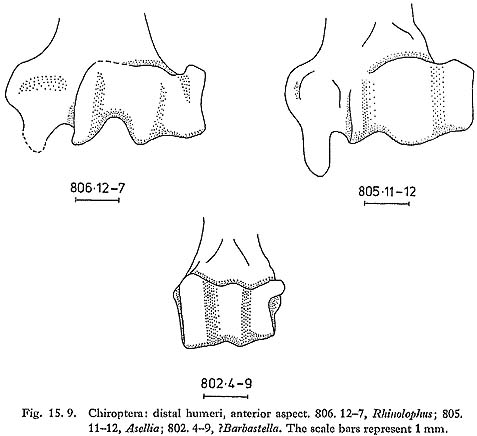

A single species of Erinaceus occurs today in the Near East (Harrison, 1964); this is a typical Boreal Eurasiatic element, occurring commonly in Turkey and down the Levant coast, but not penetrating into drier areas; it is commonest in scrub habitats, and along scrub and grassland margins. Erinaceus is commonly reported from Pleistocene sites in the Near East; the status of E. sharonis and E. carmelitus, described by Bate (1932; 1937) from the Mount Carmel caves, is uncertain. Soricidae 15.2.3.3 Crocidura sp. (Fig. 15. 8)

Crocidura is the only genus of shrew represented at Douara Cave; four mandibles were found, of which three are edentate and one has M1 and M2 (Fig. 15. 8). Measurements are as follows:

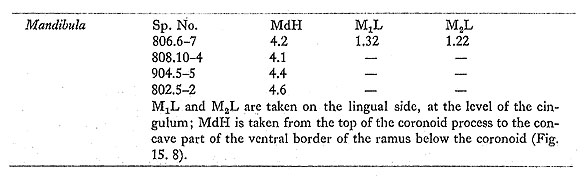

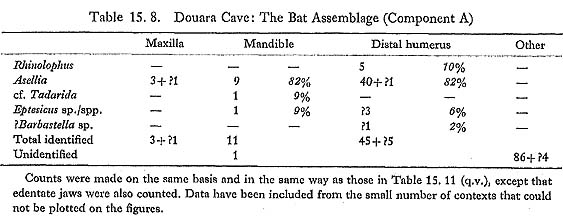

Crocidura is a notorious problem genus. Harrison (1964) recognizes four Near Eastern species; in descending order of size, these are C. lasiura, C. leucodon, C. russula and C. suaveolens. The first three are restricted to fairly well-vegetated habitats, and are found in Turkey and down the higher rainfall area of the Levant Coast. C. suaveolens occurs in this area too, but also penetrates into more arid areas in the Negev and Sinai. The Douara specimens are relatively small, about the size of modern C. nussula or C. suaveolens; but this is an inadequate basis for specific identification. Crocidura has been reported from several sites in the Near East (e.g. Bate, 1937; Haas, 1972); the status of the two species described by Bate from Tabun, C. xanthippe and C. katinka, is uncertain. CHIROPTERA Bat bones are fairly common, especially in one part of the deposits (Fig. 15. 56). A number of species are represented, and I am grateful to Mr. J. E. Hill of the British Museum (Natural History) for his kind assistance in their identification. Only maxillae, mandibles and distal humeri were used for identification.

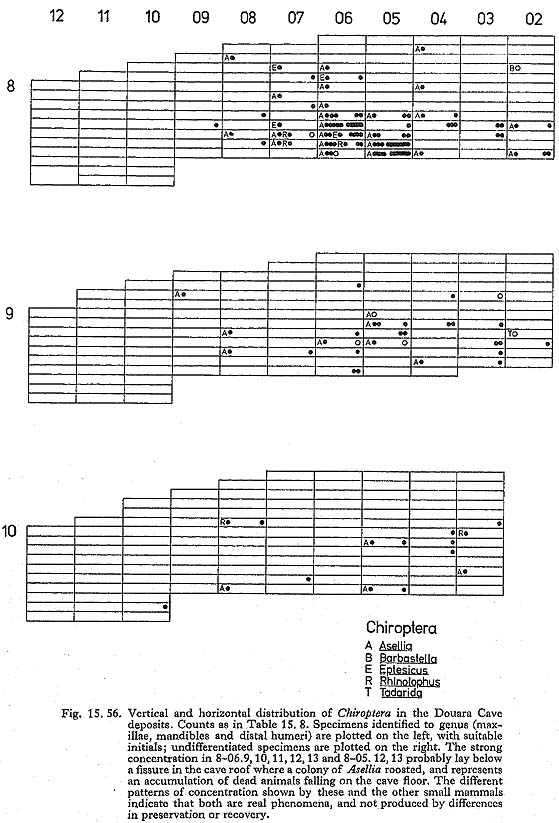

Rhinolophidae 15.2.3.4 Rhinolophus sp. (Fig. 15. 9)

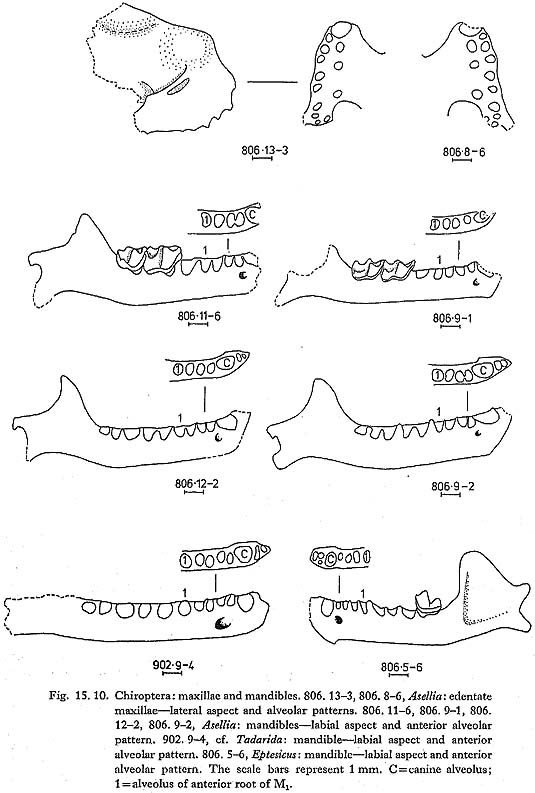

Several distal humeri compare closely with Rhinolophus spp. (Fig. 15. 9). Harrison (1964) lists five Rhinolophus species from the Near East; the genus is provisionally reported from Tabun (Bate, 1937) and from Palegawra (Turnbull and Reed, 1974). Hipposideridae 15.2.3.5 Asellia sp. (Figs. 15. 9 and 10)

Asellia is the commonest bat of the Douara Cave fauna (Table 15. 8). Distal humeri are abundant (Fig. 15.9); three edentate maxillae (dental formula -113) have the profile and single upper premolar characteristic of the genus (Fig. 15. 10); and there are several mandibles (df 2123), two retaining M3, which shows the posterior reduction found in this genus (Fig. 15. 10). Harrison (1964) comments that Asellia tridens is one of the most ubiquitous bats in Arabia; it has a typical Saharo-Sindian distribution, being found as far east as India, and west into North and East Africa, but not penetrating northward into Turkey or into the driest parts of the Near East. It is a colonial species, living in dry caverns and dark ruins.

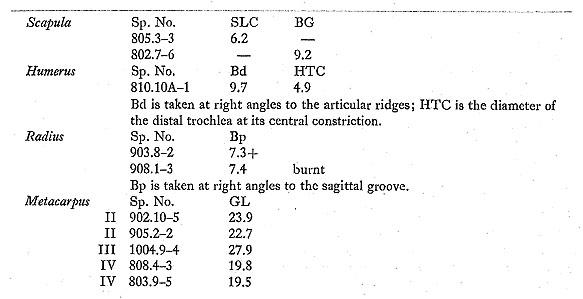

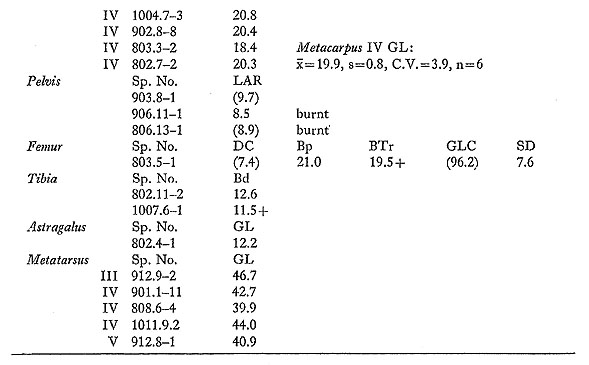

Molossidae 15.2.3.6 cf. Tadarida sp., apparently not T. teniotis (Fig. 15. 10) A slender, edentate mandible (df 2123) is very similar to Tadarida (Fig. 15. 10), and has only two incisor alveoli. This would seem to exclude T. teniotis, the only species that is found as far north as Palmyra today, which has three lower incisors. Three other species are known from the Near East (Harrison, 1964), all of which have two lower incisors and occur today only far to the south of Douara Cave, in southern Arabia and North Africa. Vespertilionidae 15.2.3.7 Eptesicus sp./spp. (Fig.15.10) A mandible with M3 (df 3123) compares closely with Eptesicus and has the typically reduced posterior part of M3. Three distal humeri, one of which is considerably larger than the other two, also resemble Eptesicus. Four species are recorded from the Near East (Harrison, 1964). 15.2.3.8 ?Barbastella sp. (Fig. 15. 9) A distal humerus (Fig. 15. 9) is very tentatively referred to Barbastella; B. barbastellus occurs considerably to the north of Douara Cave, while B. leucomelas is known from Sinaiand Eritrea (Harrison, 1964), LAGOMORPHA Leporidae 15.2:3.9 Lepus sp. Hare bones are abundant. Many are juvenile (see below, p, 65); measurements of adult specimens are as follows:

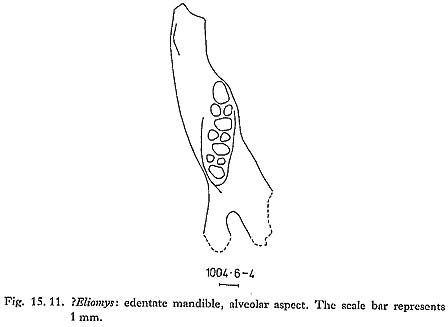

As the figures show, these were fairly small hares. Three species of hare used to be recognized in the Near East: Lepus europaeus, a large northern species; L. capensis, a smaller southern species; and L. arabiciis, a desert specie with large tympanic bullae (Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, 1951). More recently (see Fetter, 1961; Harrison, 1972), much of the wide variation that exists has been shown to be clinal, and the tendency has been to regard all Near Eastern hares as belonging to a single highly polymorphic species, L. capensis, whose distribution extends from Norway to South Africa. Some of this variation undoubtedly relates closely to environmental conditions, size tending to decrease with increasing temperature, and tympanic bullae becoming larger in semi-arid and arid environments. Bate's comment that the Lepus at Mugharet el-Wad was "of considerable size" (Bate, 1937; no measurements are given) suggests that this may have been larger than the Douara Cave Lepus, just as modern hares from the Levant coast (L. c. syriacus) are considerably larger than inland desert hares such as L. c. arabicus (the former L. arabicus). The scarcity of Lepus at some Near Eastern sites is surprising; it is absent from Tabun (Bate, 1937) or from Ksar'Akil (Hooijer, 1961). RODENTIA Gliridae 15.2.3.10 ?Eliomys sp. (Fig.15.11)

Only one glirid specimen was found: an edentate mandible, with an alveolar tooth row length of ca. 5.1 mm (Fig. 15. 11). Its alveolar pattern, each molar having one large posterior and two smaller anterior alveoli, is found in Eliomys and in Myomimus (Philistomys). The offsetting of the posterior alveoli seen in the Douara Cave specimen is characteristic of Eliomys (Tchernov, 1968: 19 and Fig. 7b); Myomimus roachi as figured by Tchernov (1968: Figs. 4-6) is more robust, and the posterior alveoli are not offset. On this rather slender basis, the Douara specimen is provisionally identified as Eliomys. Most dormice are animals of woodland or scrub habitats, and climb well; but Myomimus and Eliomys melanurus are both atypical. Myomimus roachi is fairly common in cave sites in the Levant. and survived to the Bronze Age in Israel (Tchernov, 1968); M. personatus, found today in southern Russia and in Bulgaria, lives in open country. Eliomys melanurus is still found today in the Near East; it is described by Harrison (1972) as aberrant and highly specialized, living in treeless habitats in steppe desert and above the tree line in the higher mountains in Lebanon. Harrison suggests that Eliomys entered the Near East during a period of more temperate climate and then, with increasing aridity, became adapted to treeless conditions. Eliomys has been reported from Natufian and later sites by Haas (1952) and by Tchernov (1968; 1975); the Douara Cave specimen is considerably earlier. Spalacidae 15.2.3.11 Spalax cf. ehrenbergi agg. (Fig. 15. 12)

Spalax is uncommon at Douara Cave; specimens are illustrated in Fig. 15.12.Measurements are as follows:

M1 has two lingual folds, which is regarded as characteristic of the S. ehrenbergi group. The taxonomy of Spalax is difficult and confused. The recent tendency has been to lump all living Near Eastern mole rats together as a single species, S. leucodon (Harrison, 1972) or S. ehrenbergi. Work by Nevo (1969), however, has shown that there are several chromosome races in Israel and neighboring areas, distributed in relation to increasing aridity. The scarcity of natural hybrids between these races, together with the results of mating trials, suggest that these are sibling species within a superspecies, masked by convergent adaptation; genetic isolation has probably developed as a consequence of low mobility and strong territoriality in localized and often physically isolated populations. Spalax is a highly specialized burrower, living on the underground storage organs of plants; it is found where these are found, in a wide variety of habitats, but is absent from true desert: Nevo (1961) has shown that its southern boundary in the Negev corresponds with the 100mm isohyet. Size is correlated with rainfall: adults from the desert edge in the Negev weigh around 100 g, while adults from northern Israel, where rainfall is around 800 mm, can weigh over 300 g. Spalax has been widely reported from Pleistocene sites in the Near East, and a number of species have been described (Turnbull, 1975; Tchernov, 1968). Despite these reports, the presence of more than a single population at any site has not been demonstrated,3 and the question needs critical re-examination in the light of Nevo's work. The Douara specimens agree with Tchernov's material from Israel in having two lingual folds in M1; their relatively small size would be typical of animals living near the desert edge today. Dipodidae 15.2.3.12 Allactaga sp. (Figs. 15. 13, 14, 15 and 16)

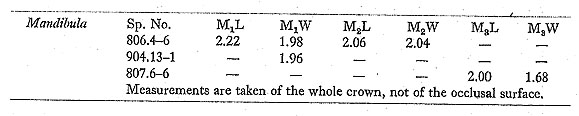

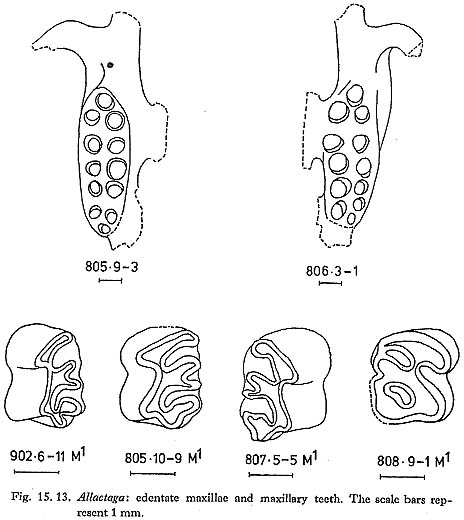

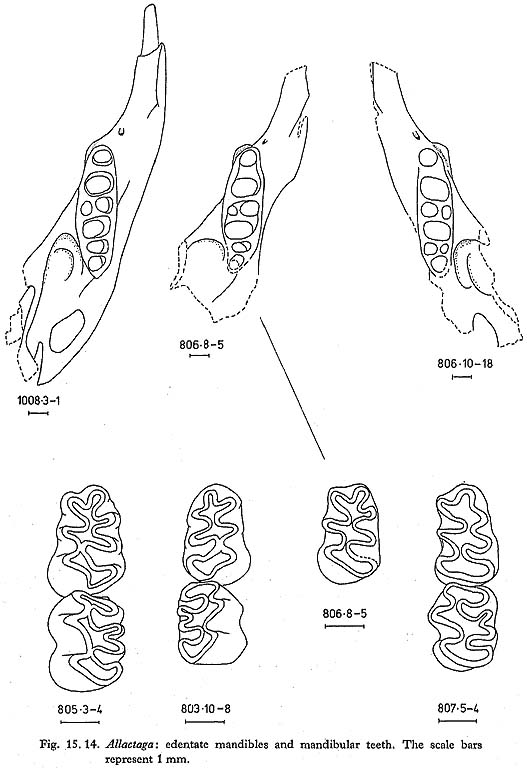

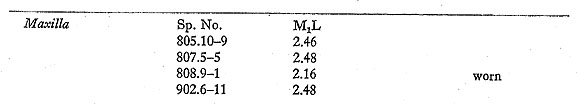

Edentate jaws of Allactaga are fairly common; the few teeth that were found are typical of the genus (Figs. 15. 13 and 14). Measurements of the teeth are as follows:

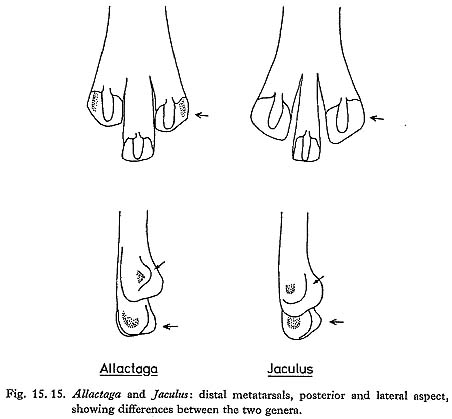

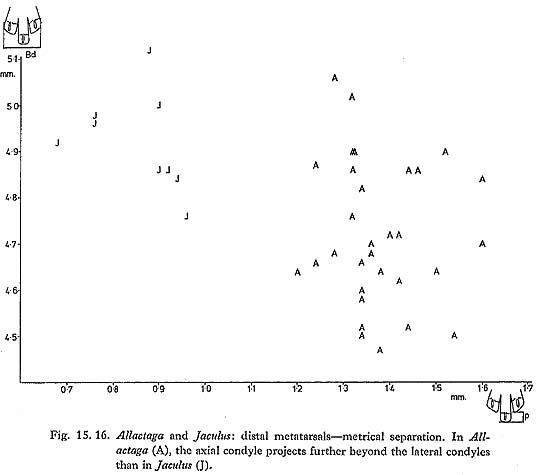

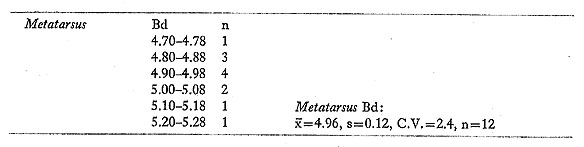

Jerboa metatarsi are relatively large and very characteristic; in the Douara Cave samples they were more abundant than jaws (Table 15. 9). Metatarsi of Allactaga and of Jaculus are readily distinguished morphologically (Fig. 15. 15) and metrically (Fig. 15. 16); distal widths of the Allactaga metatarsi are as follows:

The low variability suggests that only one species is present. Allactaga euphratica is now thought (Atallah and Harrison, 1968) to be the only Near Eastern species of Allactaga; it is widely distributed in the northern part of the Arabian peninsula, Asia Minor, the southern part of the USSR, and eastward as far as Afghanistan. It is basically an upland steppe species, preferring rocky surfaces and harder soils (Naumov and Lobachev, 1975). Allactaga is surprisingly scarce as a Pleistocene fossil in the Near East; apparently the only previous record is from Baradostian levels at Warwasi in western Iran (Turnbull, 1975). It is absent from all the Israeli sites (Tchernov, 1968; 1975), and is not found in Israel today, but the related Parallactaga is reported from the much earlier site of 'Ubeidiya (Haas, 1966). 15.2.3.13 Jaculus sp. (Figs. 15. 15, 16 and 17)

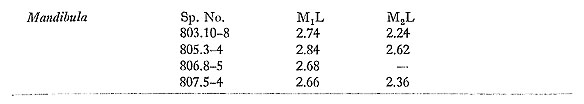

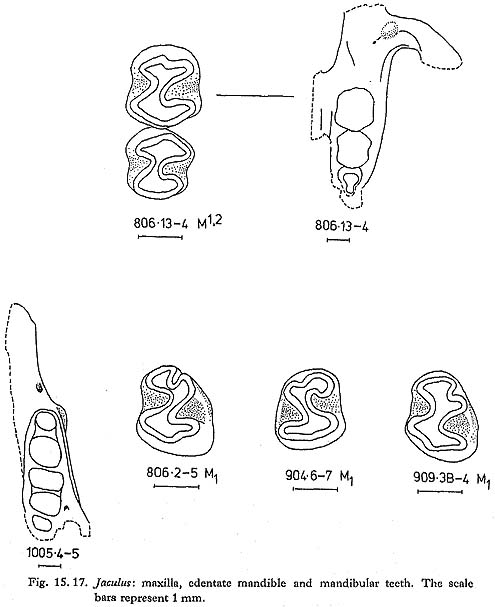

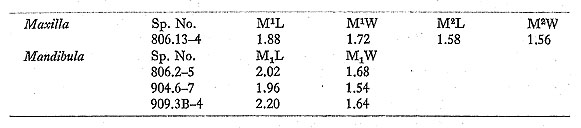

Jaculus is less common than Allactaga in the Douara Cave samples (Table 15. 9). Relatively few jaws and teeth were found (Fig. 15,17); measurements of the teeth are as follows:

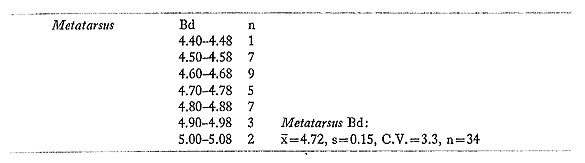

As in Allactaga, metatarsi are commoner than jaws and teeth (Figs. 15. 15 and 16); their distal widths are as follows:

Two species of Jaculus occur today in the Near East: J. orientalis, a larger, North African species, whose distribution extends into Sinai and Israel; and the smaller J. jaculus, which is widely distributed in North Africa, across the Arabian peninsula, and into southwestern Iran (Harrison, 1972). The low variability of the Douara Cave metatarsal measurements suggests that only one species is present; the teeth are in the same size range as modern J. jaculus. Harrison (1972: Fig. 179) describes an enamel crest that bridges the external re-entrant fold in M1 of J. orientalis, and says that this is absent in J. jaculus. This crest is present in the Douara Cave M1s (Fig. 15. 17), though not as strongly as Harrison illustrates in J. orientalis. The Jaculus species are highly-specialized desert-living jerboas. Laboratory studies of J. orientalis have shown that it can s urvive for long periods and gain weight on a diet of nothing but dry wheat and barley (Kirmiz, 1962); J. jaculus survives but loses weight on a diet of whole barley, and thrives on a more mixed diet without any water (Schmidt-Nielsen, 1964). J. jaculus is equally at home in sand desert and in stony steppe, but prefers sandy areas for making its burrows (Harrison, 1972), This is apparently the first record of Jaculus from a Pleistocene site in the Near East; it has been recorded from Pleistocene sites in North Africa (Turnbull, 1975). |

|

3 Tchernov (1968) divided his material into three species: S. ehrenbergi, of medium size and present throughout his sequence and today, and two extinct forms; S. neuvillei, which is smaller and found in his earlier samples, and >S'. kebarensis, which is larger and found on later sites. All three are seen as interrelated members of the "Microspalax" group. The case for the existence of three species does not seem entirely convincing, however. In the samples in which the presence of two species is suggested, as for instance 5. ehrenbergi and S. neuvillei from Oumm Qatafa, there is considerable overlap in the measurements given, and the combined range for both species is no larger than the ranges cited for modern S. ehrenbergi. Most of the illustrated specimens of S. neuvillei are rather young, and it seems possible that S. neuvillei is an artificial segregate of smaller and younger individuals chosen from a single population. In keeping with this suggestion, variances for the two species at Oumm Qatafa are often much lower than variances quoted for modern S. ehrenbergi (Tchernov, 1968: Tables 7 and 12). Similarly, S. kebarensis from the later sites may be an artificial segregate of larger and older specimens.[return to the text] |