CHAPTER 15

The Animal Bones from the 1974 Excavations at Douara Cave

Sebastian Payne

Trinity Collage, University of Cambridge

| ( 1 / 10 ) |

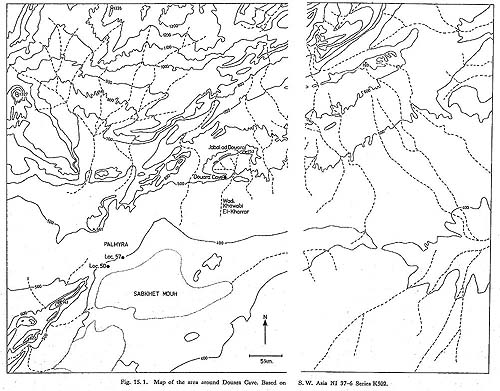

15.1 INTRODUCTIONDouara Cave, a Paleolithic site near Palmyra in central Syria, was discovered by the Tokyo University Scientific Expedition to Western Asia in 1967 (Suzuki and Kobori, 1970), and was excavated in 1970 (Suzuki and Takai, 1973, 1974) and in 1974 (Hanihara and Sakaguchi, 1978; Hanihara and Akazawa, 1979). 15.1.1 Location and modern setting ofthe site1Douara Cave lies about 18 km northeast of Palmyra (Tadmor), on the south side of a rocky spur of the Jabal ad Douara (Fig. 15. 1; for more details, see Suzuki and Takai, 1973, and Hanihara and Sakaguchi, 1978). The cave mouth faces southeast, and is about 550 m above sea level; the cave is relatively deep and narrow, and is well sheltered from the midday sun. To the north, the rocky mountain massif behind the Jabal ad Douara rises in places to over 1300 m above sea level. To the south, slope and terrace deposits drop more gently down to a large saline playa, the Sabkhet Mouh, which forms the floor of the Palmyra Basin; its lowest point is below 370 m above sea level, around 20 km SSW of the cave. Just to the north of the spur in which the cave lies is the Douara Basin, about 8×5 km in size; this is dissected and drained by the Wadi Khawabi El-Kharrar, which then cuts through the spur and runs down toward the Sabkhet Mouh.

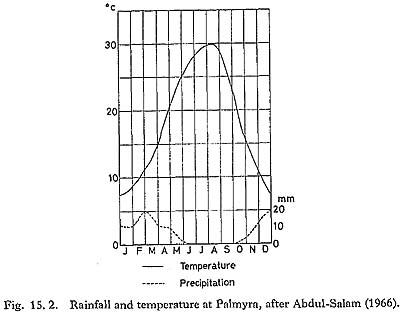

The modern climate of the Palmyra area is semi-arid (Fig. 15. 2). Winters are cool, with average temperatures falling to 7-8°C, and often dropping below the freezing-point at night. Summers are hot and dry, with average temperatures rising to about 30°C, and daily maximums often above 40°C. Annual rainfall averages 125 mm, most of which falls between December and March; falls of snow are not uncommon. As is typical of semi-arid climates, annual rainfall varies widely: 66 mm in 1973, for instance, was followed by 269 mm in 1974. In years with higher winter rainfall, as in the winter of 1973/74, the Sabkhet Mouh fills with water. In 1973/74, the water reached 377 m above sea level, and some water still remained at the east end of the basin in October 1974. The wadis dry rapidly after rain, and for most of the year there is no surface water anywhere near the cave.

The modern vegetation is scanty, dominated by tussocks of perennial grasses, Chenopodiaceae, and Artemisia. There are no trees or scrub except for scattered Tamarix on giant nebkhas in the Sabkhet Mouh. and date palms in the few places where irrigation is possible (as in the Palmyra Oasis). The rainfall is too low for agriculture; the winter rainfall provides grazing for sheep, goats and camels but dries rapidly in late spring. 5.1.2 The 1974 excavationsThe area excavated in 1974 is shown in Fig. 15. 3 (for more details, see Hanihara and Sakaguchi, 1978). Three lines of 1 m×l m squares ran from the back wall to the front of the cave; each square was excavated in units 10 cm in depth, subdivided stratigraphically when possible, and the units were numbered downward: thus 8-08.3 is below 8-08.2, and 8-08.3A and 8-08.3B would be stratigraphic subdivisions of 8-08.3. All the excavated earth was dry-sieved by the workmen, using a mesh of about 3 mm.

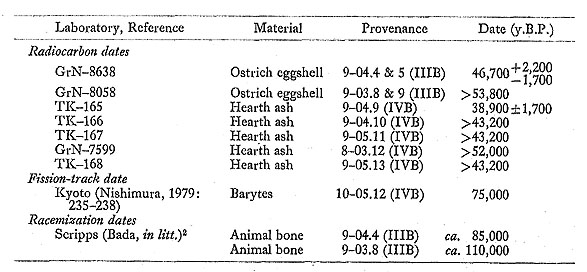

Four main stratigraphic units were recognized (Fig. 15. 4). A thin surface deposit (Horizon I) contained a wide range of finds, including sherds, pieces of glass and metal, Neolithic and Epi-Paleolithic flints, and large quantities of worn and broken Middle Paleolithic flints. Horizon II was restricted to a small area at the front of the cave, where a deep depression or pit contained an abundant Epi-Paleolithic industry; tools include backed bladelets and small trapeze-rectangles, as well as burins, end-scrapers and core- scrapers. Horizons III and IV covered the whole of the excavated area, and contained a rich Middle Paleolithic industry with an abundance of elongated blanks, prepared cores and very few retouched tools. There are considerable techno-typological differences between the industries in Horizons III and IV, but both probably reflect a similar general tradition; it is possible that there was a long time gap between the two horizons (Akazawa, in Hanihara and Akazawa, 1979: 2). 15.1.3 DatingRadiocarbon dates from the 1970 season of excavation probably received inadequate pretreatment, and are not considered further here. Three dating techniques have been applied to samples from the Middle Paleolithic horizons of the 1974 excavations, with the following results: The two finite radiocarbon dates probably mean very little; all that can really be said is that the dates of the Middle Paleolithic occupations appear to lie beyond the current effective radiocarbon range, and may, if the fission-track and racemization determinations can be taken at face value, be substantially older. No dates are available for the Epi-Paleolithic Horizon II. 15.1.3.1 Contamination A few intrusive artifacts were found in the uppermost part of Horizon III, and the excavators suggest that the upper part (Horizon IIIA) may be disturbed or secondary (Endo et al., in Hanihara and Sakaguchi, 1978: 92). A number of burrows were noted, especially toward the front of the cave (Endo, in Hanihara and Sakaguchi, 1978: 59; see also Fig. 15. 4). The number of intrusive objects is small, and, as Fig, 15. 5 shows, they are essentially confined to the top 20 cm of the deposits, except at the front of the cave.

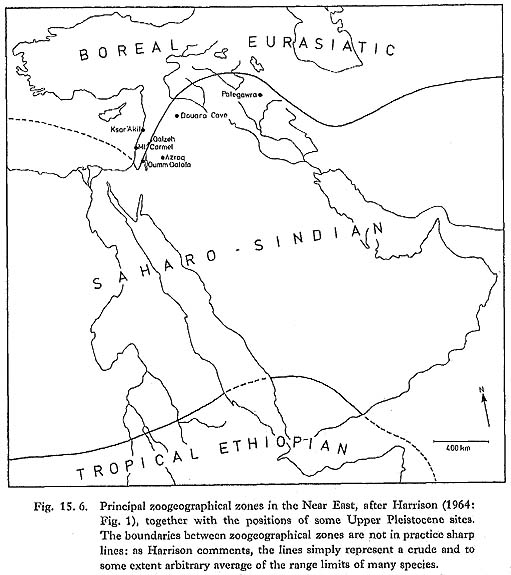

15.1.4 The animal bones: aims of this studyThis study of the animal bones from Douara Cave has a variety of aims, some regional and some local. In a regional context, a central question is that of environmental and climatic change. As in Europe, the traditional view of the Near Eastern Upper Pleistocene sequence, based on evidence such as the Mount Carmel Gazella/Dama graph (Bate, 1937), and more recently on palynological and geological studies (Farrand, 1979), has been to recognize considerable fluctuations. Changes in rainfall and water availability are seen as relatively more important in a Near Eastern context than the temperature changes that produced the ice ages of central and northern Europe, however, and the relationship between the two sequences has been the subject of much debate. More recently, Tchernov (1968, 1975) has questioned the evidence for such fluctuations in the Near Eastern Upper Pleistocene sequence, stating that: "The fauna . . . displays no correlative-or indeed any-fluctuation along the entire Upper Pleistocene" (Tchernov, 1968: 7), and suggesting that the faunal sequence in Israel "proves the existence of a gradual desiccation process" (Tchernov, 1968: 135) from the beginning of the Upper Pleistocene to the present (Tchernov, 1968: Figs. 6b, 6d and 6i). Today, Douara Cave lies close to the zoogeographic boundary between the Boreal Eurasiatic and Saharo-Sindian zones (Fig. 15. 6; Harrison, 1964: 4-5). To the north and west, the mountains of the Levant coast and southern Turkey form the southern rim of the colder, wetter, Boreal Eurasiatic zone. Most of the cave sites that have been excavated in the Near East lie within this zone, and their fossil faunas (e.g. Ksar'Akil: Hooijer, 1961; Mount Carmel: Bate, 1937) are dominated by Boreal Eurasiatic species. To the south, the steppe and desert core of the Arabian peninsula forms part of the Saharo-Sindian zone, with a fauna adapted to the arid conditions of this zone. Douara Cave is one of the few cave sites that have been excavated within this zone, and can be expected to contribute to our currently poor knowledge of the Saharo-Sindian fauna during the Pleistocene. (Although if Tchernov's hypothesis is correct, we would expect conditions to have been wetter and that we would find more Boreal Eurasiatic species among the Douara Cave fauna than are found in the area today).

In more local terms, the Douara Cave animal bones are one source of evidence about past environmental conditions in the Palmyra Basin. Wetter conditions clearly existed at some time in the past, as evidenced by raised terraces and other evidence of higher lake levels round the Sabkhet Mouh (Fig. 15. 1). The maximum level reached by the lake was about 397 m above sea level, which is 20 m above the maximum level reached in 1973/74, and about 30 m above the lowest point on the modern lake bed. Lacustrine silts at Locality 57 have been dated to around 19,000 y.B.P.; a piece of Phoenix (date palm) bark at Locality 50, in circumstances taken to suggest a high lake level, gave a date of 38,500 y.B.P.; and a gypsum crystal from the 397 m-terrace gave a fission-track date of 70,000 y.B.P. (Sakaguchi, in Hanihara and Sakaguchi, 1978: 5-28). These dates, however, even if taken at face value, do not tell us whether the lake was a permanent feature over the whole of this timespan, or whether high stands were separated by dry periods. The high stands need not necessarily have been of long duration: the brief high stand in 1973/74 was marked by wave-built terraces, and by cliffs in places almost 1 m high. If the animal bones from the cave suggest conditions substantially wetter than those of today, this suggestion would indicate that the cave was occupied while the lake was in existence; but if drier conditions are suggested, this would indicate that there was no lake at the time. Another central concern of this study is the subsistence and subsistence technology of the people who used the cave. Questions that should be considered include: Which species were hunted? What were their relative importance as food sources? What hunting methods were used? Is there any evidence of strongly selective hunting of the kind that has been suggested as an early step in the direction of animal domestication? How were the animals butchered? Was occupation of the site seasonal? All these questions should be seen in a broad context: the meat represented by the animal bones in relation to other food sources; the subsistence economy in relation to environmental conditions and constraints; and the site in relation to the area and to other sites or neighboring areas that might offer complementary resources. Many of these questions require larger samples and more data than are available from a single season of excavation; but data and tentative conclusions are given whenever possible. |

|

1 As I have never visited the site, these notes are taken from the sources cited, from conversations with members of the expeditions, and from photographs of the area.[return to the text] 2 Provisional amino-acid racemization dates calculated from the m situ rate constant 1.02×10-5 yr-1 calibrated for the Tabun site, Mount Carmel, Israel (Masters, 1982).[return to the text] |