GENERAL DISCUSSION

Estimation of the Stature

The stature of the Minatogawa man was estimated according to the methods of Peason (1899) and of Fujii (1960). The estimated statures using the femora by Fujii's method are 1532, 1499, 1556, 1499 mm in MI , MII , MII , MIII , MIII , MIV , MIV , respectively. The value for MIII , respectively. The value for MIII seems too great when the relative shortness of her tibia is taken into account. In estimating statures by Peason's formula, various kinds of bone are used. The ranges are from 1535 to 1565 mm in MI seems too great when the relative shortness of her tibia is taken into account. In estimating statures by Peason's formula, various kinds of bone are used. The ranges are from 1535 to 1565 mm in MI , from 1430 to 1473 in MII , from 1430 to 1473 in MII , from 1449 to 1523 mm in MIII , from 1449 to 1523 mm in MIII , and from 1430 to 1491 mm in MIV , and from 1430 to 1491 mm in MIV , If the mean of the range estimated by Peason's method is taken for the stature of Minatogawa people, it is 155 cm in MI , If the mean of the range estimated by Peason's method is taken for the stature of Minatogawa people, it is 155 cm in MI , 145 cm in MIII , 145 cm in MIII , 149 cm in MIII , 149 cm in MIII , 146 cm in MIV , 146 cm in MIV . These statures are somewhat smaller than the Neolithic Japanese as well as the Recent Japanese (Hiramoto, 1972). . These statures are somewhat smaller than the Neolithic Japanese as well as the Recent Japanese (Hiramoto, 1972).

Though this kind of data are not many, Ogata (1973) estimated the stature of the Early Neolithic (B. P. 9,000-5,000) Japanese according to Peason's method (1899) using the femur. It is 157.5 cm in the males and 147.1 cm in the females, while the corresponding value of the Minatogawa male is 156.1 cm and the mean values of the same females are 144.5 cm. The statures of Minatogawa Man are slightly smaller than those of Early Neolithic Japanese. If the stature of the Minatogawa people represents the stature of the Upper Paleolithic Japanese, the slight increase from this age to the Early Neolithic may be continuous to the gradual increase from the Early Neolithic to the Late Neolithic.

Summarized Characters of Each Individual

MI: moderately robust old male, having a short stature, rather slender limbs with bigger hands and feet except for short heels, narrow shoulders, and a robust pelvis with a large inlet.

MII: gracile old female, having a short stature, slender limbs, a narrow shoulders, and a narrow but rather stout pelvis with a small inlet.

MIII: gracile matured female: having a rather short stature, slender and long limbs with long hands and feet except for short heels, narrow shoulders, and a narrow and gracile pelvis with a moderate inlet.

MIV: old female, having a short stature, strong upper limbs with wide shoulders, rather slender lower limbs with short heels, a narrow but robust pelvis with small inlet. The sex of this individual may be female, though there is some doubt.

The Position of Minatogawa Man in the Course of Evolution

As mentioned at the beginning of this report, the time of the Upper Paleolithic Sapiens is known in Eastern Asia, though the skeletal remains are not rich. No description of a postcranial Neanderthaloid skeleton has been found in Eastern Asia, although there are several postcranial skeletons from Sinanthropus. The problem is the uncertainty of the characteristics of the postcranial skeleton in the Sinanthropus in relation to the Recent Sapiens in Eastern Asia, because the former is not as different from the latter as is the Neanderthaloid.

At the present stage, it is quite difficult to solve this problem. However, as far as the characteristics of humeri and femora are concerned, Minatogawa man shows rather close resemblance to the Sinanthropus and slight resemblance to the West European Neanderthals. As a tentative speculation, based on the characters of postcranial bones, it is likely that the Sinanthropus might have evolved to certain sapiens populations, one of which became the Minatogawa people, without acquiring the robust characters the West-European Neanderthals had, though those populations had passed their own stage of Neanderthaloid.

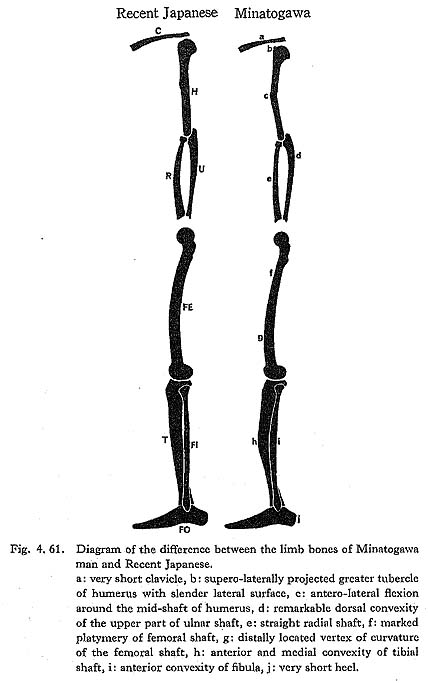

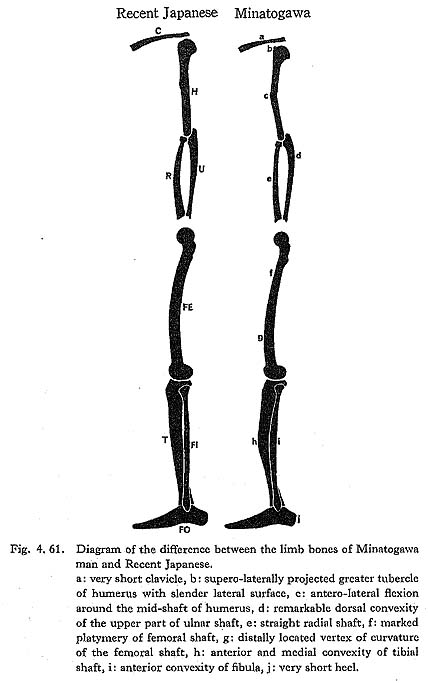

Generally, Minatogawa people have many characters which agree with those of the Early to Late Neolithic Japanese, whereas they bear also many characters which do not agree with those of the Neolithic Japanese, for example, shortness of the clavicle, antero lateral flexion of the humerus, strong curvature of the ulna, round cross-section of the femur, medial convexity of the tibia, shortness of the heel, and so on. It seems that the Minatogawa people belong to one of the oldest types of Sapiens sapiens in Eastern Asia.

REFERENCES

- Arambourg, C., Boule, M., Vallois, H., and Verneau, R. (1934)

- Les grottes paleolithiques des Beni Segoual (Algeria). Arch. Inst, Paleont. Humaine, Mem, 13: 1-188.

- Baba, H. (1970)

- On some morphological characters of Japanese lower-limb bones from the viewpoint of squatting and other sitting postures in Jomon, Edo and Modern period. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 78; 312-234.

- Barnett, C. (1954)

- Squatting facets on the European talus. J. Anat. Lond., 88: 509-513.

- Black, D. (1925)

- The human skeletal remains from the Sha Kuo Tun cave deposit in comparison with those from Yang Shao Tsun and with recent North China skeletal material. Paleontologica Sinica, 1: 1-49.

- Black, D. (1932)

- Skeletal remains of Sinanthropus other than skull part. Bull Geol. Soc. China, 11:365-374.

- Bonet, R. (1919)

- Der diluviale Menschenfund von Obercassel bei Bonn. III. Die Skelete. Verworn, Bonet and Steinmann; 11-185, Bergman, Wiesbaden.

- Bouk, M. (1911-13)

- L'Homme fossile de La Chapelle-aux-Saints. Ann. Paleont., 6, 7 et 8.

- Bunyen, K. (1942)

- Anthropologisches Untersuchung über das Femur der- Formosaner. J. Med. Assoc. Taiwan, 41: 1-126.

- Charles, H. (1894a)

- The influence of function, as exemplified in the morphology of the lower extremity of Panjabi. Anat. Lond., 28: 1-18.

- Charles, H. (1894b)

- Morphological peculiarities in the Panjabi and their bearing on the question of the transmission of acquired characters. J. Anat. Lond., 28: 271-280.

- Davis, P. (1964)

- Hominid fossils from Bed I, Olduvai Gorge, Tanganyika. A. Tibia and fibula. Nature, 201: 967-968.

- Day, M. and Napier, J. (1964)

- Hominid fossils from Bed I, Olduvai Gorge, Tanganyika: Fossil foot bones. Nature, 201: 969-970.

- Dubois, E. (1926)

- Figures of the femur of Pithecanthropus Erectus. Proe. K. ned. Akad. Wet., 29.

- Dubois, E. (1932)

- The distinct organization of Pithecanthropus of which the femur bears evidence, now confirmed from other individuals of the described species. Proe. K. ned. Akad. Wet., 35.

- Dubois, E. (1934)

- New evidence of the distinct organization of Pithecanthropus. Proc. K. ned. Akad. Wet., 37.

- Endo, B., Hojo, T., and Kimura, T. (1967)

- Pt. 2, Chapt. 7. Limb bones. Studies on the graves, coffin contents and skeletal remains of the Tokugawa Shoguns and their families at the Zojioji Temple. ed. by Suzuki, Yajima and Yamanobe (Japanese with English summary): 275-405, xxxii-xxxviii, Univ. Tokyo Press, Tokyo.

- Endo, B. and Kimura, T. (1970)

- Postcranial skeleton of the Amud Man, in: The Amud Man and His Cave Site ed. by H. Suzuki and F. Takai. The University of Tokyo.

- Finnegan, M. (1978)

- Non-metric variation of the infracranial skeleton. J. Anat., 125: 23-37.

- Fujii, A. (1960)

- On the relation of long bone lengths of limbs to stature (in Japanese with English summary). Juntendodaigaku Taiikugakubu Kiyo, 3: 49-61.

- Genet-Varcin, E. (1951)

- Les Négritos de L'ile de Luzon (Philippines) Masson.

-Kramberger, K. (1905) -Kramberger, K. (1905)- Der palaolithische Mensch und seine Zeitgenossen aus dem Diluvium von Krapina in Froatien. Mit. Anthrop. Ges. Wien, 35: 197-229.

-Kramberger, K. (1906) -Kramberger, K. (1906)- Der diluviale Mensch von Krapina in Kroatien. Ein Beitrag zur Palaoanthropologie. Kreidels, Wiesbaden.

- Hirai, T. and Tabata, T. (1928)

- Anthropologische Untersuchungen über das skelett der rezenten Japaner. Die untere Extremität. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 43. Suppl.: 1-176 (in Japanese).

- Hiramoto, Y. (1972)

- Secular change of estimated stature of Japanese in Kanto District from the prehistoric age to the present day. J. Anthrop, Soc. Nippon, 80: 221-236.

- Hojo, T. (1976)

- A few observations on roentgenopaque transverse lines (Harris's lines) in long tubular bones of early modern people. J. Pre-Medical Course, Sapporo Medical College,Vol. 17.

- Houghton, P. (1973)

- The relationship of the Pre-auricular groove of the illium to pregnancy. Am. J. Phys, Anthrop., 41: 381-390.

- Howells, W. W. (1980)

- Homo erectus ——— Who, when and where: A survey. Yearbook of Phys. Anthrop, 23: 1-23.

, A. (1920) , A. (1920)- Anthropometry. Wister Inst. Anat. Biol., Philadelphia.

, A. (1927) , A. (1927)- The Neanderthal phase of man. J. Roy. Anthrop. Inst., 57: 249-274.

, A. (1930) , A. (1930)- The skeletal remains of early man. Smithon. Miscell. Coll., 83: 1-364.

, A. (1934a) , A. (1934a)- Contribution to the study of the femur: The crista aspera and the pilaster. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop., 19: 17-37.

, A. (1934b) , A. (1934b)- The human femur: Shape of the shaft. Anthropologie, 12 suppi: 129-163.

, A. (1937) , A. (1937)- The gluteal ridge and gluteal tuberosities (3rd trochanters). Am. J, Phys. Anthrop., 23: 127-198.

, A. (1942) , A. (1942)- The adult scapula. Additional observations and measurements. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop., 29: 363-415.

- Hsu, M. (1949)

- Anthropologisches Untersuchungen der Oberextemitätenknochen der Formosa-Chinesen (Hoklo), III Über den Humerus, IV Über den Radius, V Über die Ulna. Bulletins of Anotomical Department of the National Taiwan University, Formosa, 8:1-256.

- Kikitsu, Y. (1930)

- Anthropologische Untersuchungen über das skelett der rezenter Japaner. Die Rippen. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 45. Suppl.: 380-442 (in Japanese).

- Kiyono, K. and Hirai, T. (1928a)

- Anthropologische Untersuchungen über das Skelett der Steinzeit Japaner. III. Die obere Extremität. J. Anthrop. Soc, Nippon, 43. Suppl.: 179-300 (in Japanese).

- Kiyono, K. and Hirai, T. (1928b)

- Anthropological Untersuchungen über das Skelett der Steinzeit Japaner. IV. Die untere Extremität. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 43. Suppl,: 303-494 (in Japanese).

- Klaatsch, H. (1901)

- Die wichtigsten Variationen and Skelet der freien Unteren Extremitat des Menschen und ihre Bedeutung für das Abstammungasproblem. Ergebn. Anat. Entwgsch., 10: 599-719.

- Koh, B. (1942)

- Anthropologisches Untersuchung über das Femur der Formosaner. J. Med Assoc. Taiwan, 41: 1-126.

- Lisowski, F. P. F. et al. (1957)

- The skeletal remains from the 1952 excavation at Jericho. Z. Mor. Anth., 48: 128-150.

- Manouvrier, L. (1887)

- La platycnemie chez 1'homme et chez les singes. Bul. Soc. Anthrop. Paris, 12: 128-141.

- Martin, R. (1928)

- Lehrbuch der Anthropologie. Fischer, Jena.

- Mayer, A. W. (1924)

- The cervical fossa of Allen. Amer. J. Phys. Anth. 3-2: 257-267.

- McCown, T. and Keith, A, (1939)

- The stone age of Mount Carmel. Vol. 2. The fossil human remains from the Levalloiso-Mousterian. Clarendon, Oxford.

- McKern, T. W. and Stewart, T. D. (1957)

- Skeletal Age Changes in Young American Males. Technical report. Headquarters Quartermaster Research and Development Comand. Natick., Mass.

- Mednick, L. (1955)

- The evolution of the human ilium. Am. J. Phya. Anthrop., 13:203-216.

- Miyamoto, H. (1926)

- Anthropologische Untersuchungen über das Skelett der rezenten Japaner. II. Die obere Extremität. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 40: 1-87 (in Japanese).

- Miyamoto, H. (1927)

- Anthropologische Untersuchunger über das Skellett der rezenten Japaner. III. das Becken. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 42: 1-58 (in Japanese).

- Morimoto, I. (1959)

- The influence of squatting posture on the talus in the Japanese. M. J. Sinshu Univ. 4: 269-278.

- Morimoto, I. et al. (1970)

- Secondary buried earliest Jomon skeletons, including the hip bone pierced by a bone spear tip. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 78: 235-244.

- Morimoto, I. (1971)

- Note on the flattened tibia of the earliest Jomon juvenile from Kami kuroiwa, Japan. J. Anthrop. Soc, Nippon, 79.

- Morton, D. (1926)

- Significant characteristics of the Neanderthal foot. Nat. Hist. N,Y., 26: 310-314.

- Ogata, T. (1973)

- Physical characters of the Neolithic Japanese (in Japanese). Dolmen, 1: 22-33.

- Okamoto, T. (1930)

- Anthropologische Untersuchungern über das Skelett der rezenten Jap

aner. Die Wirber. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 45. Suppl.: 9-149 (in Japanese).

- Pauwels, F. (1948)

- Die Bedeutung der Bauprinzipien des Stutz-und Bewegungsapparates fur die Beanspruchung der Röhrenknochen. Erster Beitrag zur funktionellen Anatomic und Kausalen Morphologie des Stutzapparates. A. Anat. Entwgsch., 114: 129-166.

- Pauwels, F. (1950)

- Die Bedeutung der Bauprinzipie der unteren Extremität fur die Beanspruchung des Beinskeletes. A. Anat. Entwgsch., 114: 525-538.

- Peason, K. (1899)

- Mathimatical contribution to the theory of evolution. V. On the reconstruction of the stature of prehistoric races. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc., Series A, 192: 169-244.

- Robinson, J. T. (1972)

- Early Hominid Posture and Locomotion. The University of Chicago Press.

- Sewell, R. (1904)

- A study of the astragalus. Part II. J. Anat. Physiol., 38: 423-434.

- Singh, I. (1959)

- Squatting facets on the talus and tibia in Indians. J. Anat. Lond., 93: 540-550.

- Stewart, T. D. (1959)

- Restoration and study of the Shanidar I Neanderthal skeleton in Baghdad, Iraq. Am. Philosoph. Soc. Year Book, 1958: 274-278.

- Stewart, T. D. (1960)

- Form of the pubic bone in Neanderthal man. Science, 131:1437-1438.

- Stewart, T. D. (1964)

- Shanidar skeletone IV and VI. Sumer, Baghdad, 19: 8-26.

- Straus, W. L. (1927)

- The human ilium: sex and stock. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop., 11: 1-28.

- Sunderland, S. (1937-38)

- The quadrate tubercle of the femur. J. Anat., 72: 309-312.

- Suzuki, H. (1959)

- Entdeckung eines Pleistozänen hominiden Humerus in Zentral-Japan. 1 Morphologische Untersuchung des Humerus. Anthrop. Anz., 23: 224-235.

- Suzuki, H. (1962)

- Skeletal remains of Mikkabi Man. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 70: 1-20.

- Suzuki, H. (1966)

- Skeletal remains of Hamakita Man. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon. 74: 119-136.

- Suzuki, N. (1961)

- Anthropological study of tibia in Kanto Japanese. Report of Anatomical Department of Tokyo Jikeikai Med. Coll., 22: 2638-2678.

- Tabata, T. (1928)

- Anthropologische Untersuchungen über das Menschenskelett aus TSUKUMO-Muschelhaufen. V Teil Das Becken. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon, 43 Suppl.: 739-814 (in Japanese).

- Takano, H. (1958)

- Anthropological study of scapula in Kanto, Japan. Report of Anatomical Department of Tokyo Jikeikai Med. Coll., 18: 1-47.

- Thomson, M. A. (1889)

- The influence of posture on the form on the articular surface of tibia and Astragalus in the different races and higher apes. J. Anat. Lond., 23: 616-639.

- Trotter, M. and Gleser, G. (1958)

- A re-evaluation of estimation of stature based on measurements of stature taken during life and of long bones after death. Am J. Phys. Anthrop., 16: 79-123.

- Vallois, H. (1932)

- L'omoplate humaine. Etude antomique et anthropologique. Bul. Soc. Anthrop. Paris, 3-8: 3-153.

- Wang, Y. (1950)

- Anthropologisches Untersuchungen über die Unterschenkelknochen der Formosa-Chinese (Foklo). Bulletins of the Anatomical Department of the National Taiwan University, Formosa., 9: 1-118.

- Weidenreich, F. (1941)

- The extremity bones of Sinanthropus pekinensis. Palaeont. Sinica, D-5, 110: 1-150.

- Weidenreich, F. and Koenigswald, G. von (1951)

- Morphology of Solo man. Anthrop. Papers Am. Mus. Nat. Hist., 43: 205-290.

- Wells, C. (1967)

- A New Approach to Paleopathology: Harris's Lines. In Diseases in Antiquity, ed. D. Brothwell, C. Thomas.

- Woo, J. and Chia, L. (1954)

- New discoveries about Sinanthropus pekinensis in Choukoutien. Scientia Sinica, 3: 335-351.

- Woo J. (1959)

- Human fossils found in Liukiang, Kwangsi, China. Vertebrata Palasiatica, Vol. III, No. 3.

|

, MII

, MII , MIII

, MIII

-Kramberger, K. (1905)

-Kramberger, K. (1905) , A. (1920)

, A. (1920)