1. INTRODUCTION

Syria is situated in the northwestern part of the Arabian Peninsula. It occupies an area of about 185,000 km2. The Syrian territory borders Jordan on the south, Iraq on the east, Turkey on the north and Lebanon and the Mediterranean on the west (Fig.IV-1).

Figure IV-1. Map showing the tectonic scheme of Syria and adjacent territories, simplified from the map drawn by U.S.S.R. geologists. |

Until recently, there have been few geomorphological and geological investigations of Syria and its adjacent area. However, with the beginning of petroleum exploitation in the northeastern and eastern parts of Syria, geological investigations have been carried out ranging over most of the territory, and excellent geological maps (1: 200,000 and 1 : 1,000,000 scales) have been made by Soviet geologists. But owing to a lack of large-scale topographical maps - topographical maps on scale of 1 : 50,000 have not been prepared yet for area east of the Aleppo-Hama-Homs-Damascus line, and we relied upon 1 : 200,000 scale maps during our investigation - the study on this area is not at a level permitting detailed discussion.

In this paper the author describes and attempts to clarify the various topographical and geological characteristics of Syria referring to the results of many foreign investigators and available topographical map, and tries to set up a division of geomorphologic provinces and geomorphologic subprovinces for the Syrian territory.

2. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF SYRIA

The topography of Syria can be divided into two parts: mountains in the west and plateau in the east. The mountainous area consists of the 1,200-1,500 m Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh range, running south from the Hatay region of Turkey, and the 2,500-2,800 m Anti-Lebanon and Hermon Mountains in the southwest, the last two running en échelon along the borders of Lebanon and Israel. A low-relief, undulating plateau, occupying more than 90 % of the Syrian territory, develops to the east of these mountain ranges. The boundary between the mountains and the plateau is marked in the north by the Ghab depression and in the south, between Horns and Damascus, by a difference of the directions of the main ridges of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains and the ridge branching out of it (Figs.IV-2, 3).

Figure IV-2. Summit level map of Syria, eliminating valleys less than 5km wide (Contour interval: 50m). |

Figure IV-3. Geological map of Syria, simplified and modified from the map drawn by U.S.S.R. geologists. |

The Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh range is about 40 to 50 km wide east-west and about 140km long north-south. It is highest at a point east of al-Latheqiyeh, gradually decreasing in height to about

500 m south toward Homs-Tripoli line. Its eastern slope falls sharply to the Ghab depression. This slope is a fault scarp 1,300 m high. The Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh range is a westward tilted block, and consequently, deep valleys have been formed on its western slope.

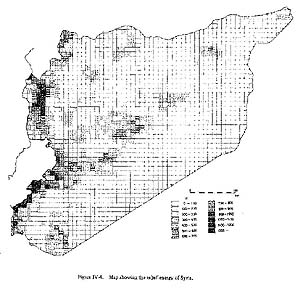

The Anti-Lebanon Mountains run NNE-SSW, obliquely to the Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh range but parallel to the Lebanon Mountains. They have their highest ridge, about 2,600 m, on the western margin along the Bekka Valley and a gentle slope on the east. These mountains are an eastward tilted block facing the Syrian plateau. The Palmyrides branch out of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains about 20 km north of Damascus. The altitude of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains decreases to 1,500 m around the Damascus-Zahle line but again reaches up to 2,800 m in the Hermon Mountains. In Syria these mountains have maximum relief-energy (Fig. IV-4) and steep slopes, but to the south of these mountains the altitude abruptly decreases, and finally reaches about 600 m in the Hawran basalt plateau near the Jordanian border.

Figure IV-4. Map showing the relief-energy of Syria. |

The Syrian plateau - called Shamiya or Badiet esh Sham in Arabic - extends east from these mountains to the Euphrates River. Up to the Second World War, geological, geomorphological and pedological investigations of the Syrian plateau were not extensive. But since German geologists began to join the investigations there, drawing on experience from the desert of North Africa, the geologic history of Syria gradually has become clearer.

The Palmyrides, which break the monotony of the Syrian plateau, branch off the Anti-Lebanon Mountains around Dmeir, northeast of Damascus. These mountains run approximately northeast for about 400 km to the Jabal al-Bishri range near the Euphrates River. Their altitude is uniformly 1,000-1,300 m. The relative height of the mountains above the plateau reaches 400 to 900 m. Another mountain, Jebel ad-Drouz, near the border with Jordan, is 1,800 m high and consists of a mass of basaltic lava flow.

Volcanic activity occured repeatedly in the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene in the Hawran and Jebel ad-Drouz regions. The lava flow topography of this region contrasts sharply with the monotony of the Syrian plateau.

The main drainages in Syria are shown in Figure IV-5.

Figure IV-5. Map showing the drainage pattern of Syria. |

The Euphrates River flows southeast across the northeastern part of Syria from its source in the Tourous Range, and divides the Syrian plateau into two parts. No large tributaries join the Euphrates from the right bank, but on the left bank the Nahr el-Balikh joins it at al-Raqqa and the Nahr el-Khabour joins it between Deir az-Zor and Mayadin.

The Orontes River flows from its source in the Bekka Valley through the Bahr el-Houmous north along the boundary between the Syrian plateau and the Jebel an-Nusseriyeh range. It passes through the Ghab depression, bends sharply west, then southwest in the Hatay region of Turkey, and finally enters the Mediterranean.

The outline of geology in Syria is summarized as below (Fig. IV-3).

The folded Precambrian rocks of the Arabian-Nubian shield are exposed along the western margin of the Arabian Peninsula between the Aqaba Gulf and the Dead Sea (Fig. IV-1). The main direction of the tectonic framework of the basement rocks coincides with that of the African platform. The Precambrian basement rocks are covered with Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments and are not exposed in the inland areas of the Arabian plateau. The local differences of thickness of these post-Precambrian sediments depends upon the differences of the block structure of the basement rocks.

In the western part of Syria near the Lebanon border, the Bekka-Ghab depression is the extention of the Great Rift Valley of Africa and Dead Sea graben and runs in an approximate north-south direction. On the other hand, the Tourous Range north of Syria is an Alpine folded area and runs east-west along the Turkish border. The position of the boundary between the Arabian plateau and the Alpine folded zone has been discussed by Dubertret (1929~55), Bogdanov (1962), Ponikarov (1964) and others, but it is still in dispute. Though the Syrian plateau is considered stable land, it has a complicated structure.

The tectonic scheme of Syria is essentially influenced by the structure of four directions as follows (Fig.IV-6):

- N5° -10°E, represented by mountains in western Syria, i.e., Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh;

- N35°-55°E, the folded mountains of the Palmyrides;

- N120°-140°E, the Aleppo uplift zone; and

- N80° -90° E, represented by Jabal Abd el-Aziz and Jabal Sinjar, the predominant directions in the Jezire region.

Figure IV-6. Tectonic map of Syria, simplified from the map drawn by U.S.S.R. geologists. |

The conjugated NE-SW/NW-SE lattice-like pattern of these four distinctive tectonic directions is the most important element in the geological structure of Syria.

The Palmyra zone runs across the Syrian plateau in a NE-SW direction (Krenkel, 1924) and corresponds to the so-called Syrian arc, the Palmyrides. It branches at an acute angle from the western mountains between the Hermon and Anti-Lebanon Mountains. The Palmyrides run for 400 km in a N30°-55° E direction to the Jabal al-Bishri near the Euphrates River. The Palmyrides are an anticlinorium and consists of a series of anticlines and synclines 30 to 50 km long.

The formation of the folds, according to Knetsch (1957), began in the early Eocene, but continued in the Neogene because Miocene and Pliocene continental conglomerates are distributed at the margins of Palmyrides.

Rows of low mountains and hills, the Aleppo zone to the north and the Sirhan zone to the southwest of the Palmyrides (Blumenthal, 1938, 1946), run NW-SE at right angles with the Palmyrides, but they are not so prominent as latter. The Aleppo zone begins northwest of Aleppo and runs in a southeasterly direction to the Palmyra zone. The Sirhan zone runs in the area between the Hawran block and Syrian central block.

The topography of the Syrian plateau, as mentioned above, is controlled by a lattice-like structure of NE and NW directions of such structural highs as the Palmyrides and the Aleppo zone. The lowlands around Palmyra, Damascus and Hatay are the sunken areas surrounded by these structural highs.

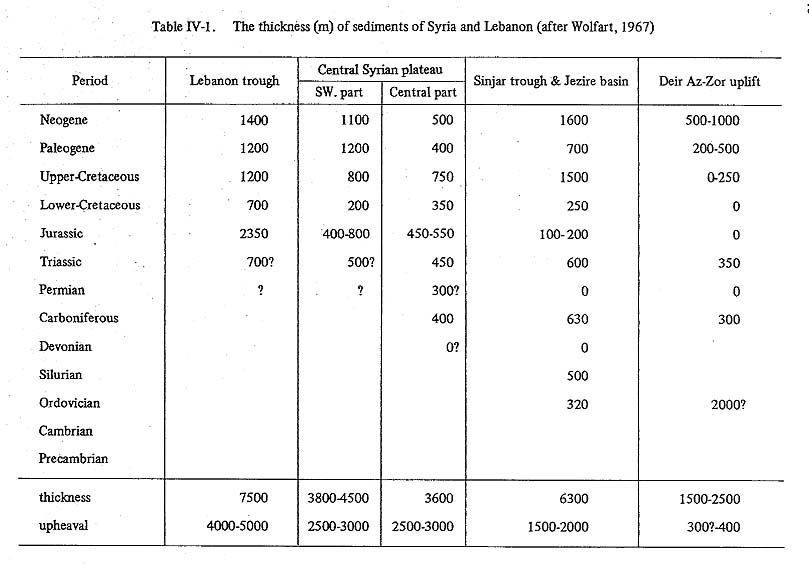

Palaeogene and Neogene deposits in the southwestern and central parts of the Syrian plateau reach thicknesses of 2,300 m and 900 m respectively (Table IV-1).

The Palaeogene transgression covered most areas of Syria except Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh, the Anti-Lebanon mountains and the Palmyrides. But the Neogene transgression occured only in the Jezire region - the area enclosed by Nahr el-Balikh, the Euphrates River and boundaries of Turkey and Iraq - centering on the Euphrates River around Aleppo and Horns, because of the relative rising of the Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh range, the Syrian plateau, Jabal ad-Drouz and the Aleppo uplift zone. The areas composed of the Palaeogene deposits have more dense wadi nets than those of the Neogene deposits, and the areas of the Palaeogene transgression and the Neogene transgression can be distinguished by the difference in the density of wadi net systems (Wirth, 1958).

The lowland along the Euphrates River is geologically known as the Mesopotamian trough and

corresponds with the border between the Syrian plateau and Zagrous-Tourous Range. The sediments piled in the lowland reach a thickness of more than 10,000 m. These consist mainly of Neogene limestones and marls.

The crustal movement on the Syrian plateau transfered with age gradually from the Palmyrides, approximately in central part of the plateau, to its margin. The Miocene and Pliocene sediments distributed in the Euphrates lowland have been folded, and further, along the frontal belt of the Zagrous-Tourous mountains, crustal movements have continued even in the Pleistocene and Holocene.

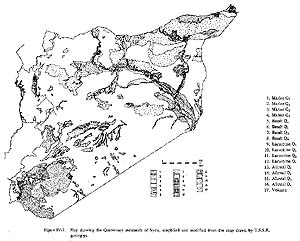

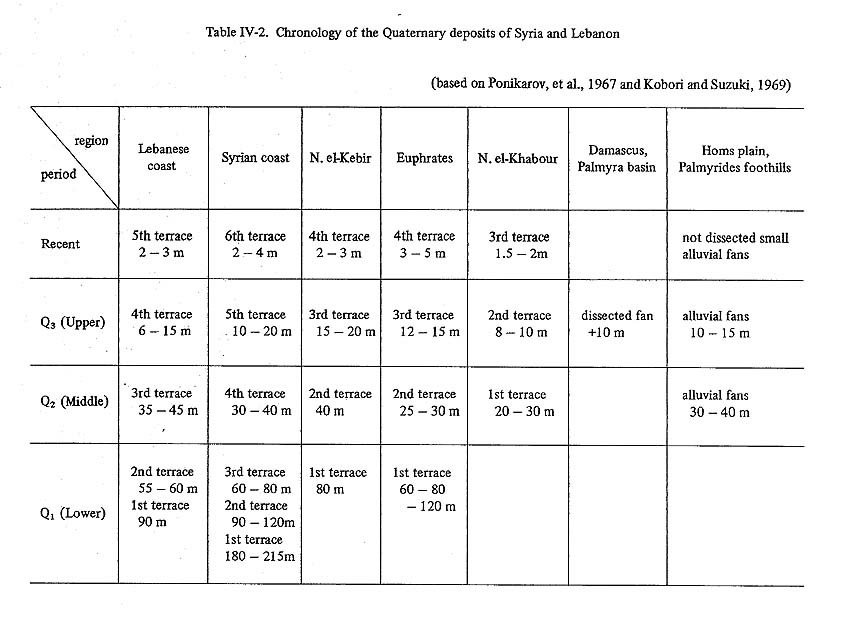

The distribution of Quaternary sediments is limited to the Mediterranean coast, the Ghab depression, the Euphrates lowland, inland basins, etc. (Fig. IV-7). These sediments form marine terraces, river terraces or alluvial fans. It is almost impossible to correlate them with those of southern Italy, the type-locality for Quaternary sediments, because of the limited extension of their geomorphic surfaces, differences in degree of dissection, and so on. At present it is difficult to correlate the marine terraces along the Mediterranean coast with the river terraces along the Euphrates River, and with the alluvial fans or wadi fans (Chapter V), on the margins of inland basins. There are a number of unsolved problems such as the estimation of local difference of the baselevel. The author refers to the chronology of the Quaternary deposits of Syria and Lebanon which is presented as a tentative plan by Ponikarov, et al. (1967) and Kobori and Suzuki(1969) (Table IV-2).

Figure IV-7. Map showing the Quaternary sediments of Syria, simplified and modified from the map drawn by U.S.S.R. geologists. |

The anticlinoria of Jebel Abd el-Aziz and Jabal Sinjar in the Jezire region run in an east-west direction. This east-west structure is an extension of the folded zone from southwestern Iran and northern Iraq. It is apparently not the continuation of the NE-NW lattice structure on the Syrian plateau. The formation of this structure would be mainly post-Miocene.

The depression which runs north-south along the western border of the Syrian plateau (the author calls it the Ghab graben after its typical place) is considered to be the northern extension of the rift system of the Dead Sea graben and the Bekka Valley graben. The extension of the Bekka Valley graben is indistinct topographically and probably runs northeast across the Syrian plateau along the northern foot of the Palmides to the Euphrates. The other linear depression, the Ghab graben, branches off from the Bekka Valley graben near Homs. The Ghab graben runs northward at an acute angle of 75° to the Bekka Valley. About 45 km north from the branching point, the depression begins to take graben-like characteristics. The western limit of this Ghab graben is marked clearly by a steep cliff which runs in a N-S direction, but its eastern limit is not always clear because the boundary between the graben and Jebel az-Zawiyeh and the Syrian plateau Is represented structurally by flexures and not by a fault.

The formation of the Ghab graben began in the Miocene, like the southern grabens such as the Bekka Valley graben, and is supposed to have been formed approximately like its present topography after the late liocene-early Pleistocene, as is indicated by the Vaumas (1957), The northern part of this Ghab graben is divided into three depressions of different directions, the Orontes, Balouaa, and Er Rouj. It disappears toward the border of the Tourous Range, the Alpine folded area (Fig. IV-8).

Figure IV-8. Geomorphological map of Syria, modified from the map drawn by U.S.S.R. geologists. |

Magmatic activities appear repeatedly in three periods:

- 1. Basaltic volcanism of the late Jurassic-early Cretaceous. The rocks exposed on the western slope of the Lebanon Mountains but not yet found on Syrian territory;

- 2. Formation of green rocks in the late Cretaceous; and

- 3. Basaltic eruptions of the Neogene-Quaternary.

The last period of volcanism started in middle Miocene as the eruption of plateau basalts in the southern part of the Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh area, in the area between Aleppo and the Palmyrides, and in the Hawran and Jebel ad-Drouz areas.

The eruption of plateau basalts is considered to be prior to the formation of the graben because the lava flows were cut by vertical and lateral faults along the margins of the Dead Sea graben (Freund et al., 1968).

According to Dubertret (1929, 1940), the Damascus basin opened to the south before the middle Miocene. Because the eruption of basalts in Hawran and Jebel ad-Drouz began in the middle Miocene, its drainage mouth is thought to have been cut off then turning it into an inland drainage basin.

During the Pleistocene the eruptions of basalt continued in extensive areas of Hawran and Jebel ad-Drouz. Both areas are located in the southern part of what was probably a depression zone between the Palmyrides and the Jordan uplift zone (Fig. IV-1), where there are fault swarms of NW-SE direction along which the eruption center is disposed. In the Hawran region basalt flowed along the Yarmouk valley and reached to the bottom of Dead Sea graben. In Jezire region, on the other hand, only small-scale eruptions occurred during Pleistocene. The basalt flow covers terrace surfaces of different ages around the volcanic area.

3. GEOMORPHOLOGIC DIVISION OF SYRIA

The topography of Syria and Lebanon already have been divided into six geomorphologic provinces by R. Wolfart (1967). However, the area can be divided into the following two geomorphologic provinces and nine geomorphologic subprovinces (Fig. IV-9), based on the various characteristics of topography and geology shown in Figure IV-1 to Figure IV-8.

Figure IV-9. Map showing the physiographic divisions of Syria. |

I. Western mountainous province

- Jebel an-Nusseiriyeh and Kurd-Dagh Mountains.

- Anti-Lebanon Mountains.

- Hermon Mountains.

- Ghab depression and intradepressions.

- Narrow coastal plains.

II. Syrian plateau province

- Central Syrian plateau.

- Palmyrides.

- Southwestern regions covered with basalt flows.

a. Jebel ad-Drouz and Jabal at-Tanf.

b. Hawran plateau.

- Jezire region

a. Rolling plateau.

b. Jebel Abd el-Aziz and Jabal Sinjar.

c. Lowland along the Euphrates and its tributaries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Abdul-Salam, A. (1965):

- Morphologische Studien in der Syrischen Wüste und dem Anti-libanon. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Freien Universität Berlin.

- Blumenthal, M. (1938):

- Die Grenzzone zwischen syrischer Tafel und Tauriden in der Gegend des Amanos (türkisch-syrisches Grenzgebiet). Eclogae Geol. Helvetiae, 31, 381 - 383.

- Blumenthal, M. (1946):

- Die neue geologische Karte der Türkei und einige ihrer stratigraphisch- tektonischen Grundzüge. Eclogae Geol. Helvetiae, 39, 277 - 289.

- Bogdanov, A. (1962):

- Sur certains problèmes de structure et d'histoire de la plate-forme de l'Europe orientale. Bull. Soc. gèol. France, 7, 898 -911.

- Dubertret, L. (1929):

- Etudes des règions volcaniques du Haouran, du Djebel Druse et du Diret el Jouloul (Syne). Reo. gèogr. phys. et gèol. dynam., 2, 275-321.

- Dubertret, L. (1932):

- Les formes structurales de la Syrie et de la Palestine. C. r. Acad. Sci., 195, 66 - 68.

- Dubertret, L. (1940):

- Sur l'âge du volcanisme en Syrie et du Uban. C. r. Soc. géol. Fr., 55 - 57.

- Dubertret, L. (1940):

- Le Sénonien dans les reacute;gions d'Antioche et de Lattaquié. C. r. Acad. Sci., 210, 737 - 789.

- Dubertret, L. (1945-48):

- Aperçu de géographie physique sur le Liban, L'Anti-liban et la Damascéne. Notes et Memoires, 4, 59 - 114.

- Dubertret, L. (1951):

- Aperéu géologique surle Kurd Dagh. C. r. Soc. géol. Fr., 1, 1 - 16

- Dubertret. L. (1955):

- Carte géologique du Liban au 1: 200,000. Beyrouth.

- Freund, R. et al. (1968):

- Age and rate of the sinistral movement along the Dead Sea Rift. Nature, 220, 253 - 255.

- Geze, B. (1956):

- Carte de reconnaissance des sols du Liban au 1 : 200,000. 1 - 52, Beirut.

- Knetsch, G. (1957):

- Eine Struktur-Skizze Ägyptens und einiger seiner Nachbargebiete. Geol. Jb. 74, 75-86.

- Kobori, I. and I. Suzuki (1969):

- Some observations on topography and settlement in the southwestern Asia. Geogr. Rev. of Japan, 42,400 - 401.

- Krenkel, E. (1924):

- Der Syrische Bogen, Cbl. Miner, etc., 9 and 10, 274 - 281 and 301 - 313.

- Pfannenstiel, M. (1944):

- Die diluviale Entwicklungsgeschichte und die Urgeschichte von Dardanellen, Marmarameer und Bosporus. Geol. Runds., 34, 342 - 434.

- Pfannenstiel, M. (1951):

- Quartäre Spiegelschwankungen des Mittelmeeres und des Schwarzen Meeres. Vierteljahrschrift der Naturfbrschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich, Jahrg. 96, Heft 2, 81-102.

- Pfannenstiel, M. (1952):

- Das Quartär der Levante I : Die Küste Palästina-Syriens. Akad. Wiss, und Literal Mainz, Abh. 7, 373 - 475.

- Picard, L. (1943):

- Structure and evolution of Palestine. Bull. Geol. Dept. Hebr. Univ., Vol. 4.

- Picard, L. (1963):

- The Quaternary in the northern Jordan valley. The Israel Academy of Science and Humanities proceedings, Vol. 1, No. 4.

- Ponikarov, V. P. et al.(1964):

- Die Tektonik des nördlichen Teiles der Arabischen Tafel. Sov. Geol., 1,39-48.

- Ponikarov, V. P. et al. (1967):

- 1 : 500,000 The geology of Syria Explanatory notes on the geological map of Syria. Part 1.

- Suzuki, H. and Kobori, I. (1970):

- Report of the reconnaissance survey on Palaeolithic sites in Lebanon and Syria. The Univ. Museum, the Univ. of Tokyo, Bull. 1.

- Van Liere, W. J. (1960):

- Observation on the Quaternary of Syria. Publication of the General Directorate of Antiquites and Museums in the Syrian Arab Republic, 5-69.

- Vaumas, E. de (1949):

- Sur la surface d'érosion polycyclique de l'Antiliban et de l'Hermon. C. r. Acad. Sci., Paris, 228, 326 - 328.

- Vaumas, E. de (1954):

- L'Amanua et le Djebel Ansarieh : Etude morphométrique. Rev. Géogr. Alpine, 42, 111-142.

- Vaumas, E. de (1956):

- La structure de la Bekka : Note complémentaire. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Egypte, 29, 181 -248.

- Vaumas, E. de (1956):

- Sur la structure et sur la surface d'erosion polycyclique du Djebel Ansarieh (Sytie). C. r. Acad. Sci., Paris, 242, 1632 - 1634.

- Vaumas, E. de (1956):

- Le Djebel Ansarieh : Étude morphologique. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Egypte, 29, 181 -248.

- Vaumas, E. de (1957):

- Plateaux, plaines et dépressions de la Syrie intérieure septentrionale (du paralléle d'Alep au paralléle de Horns) : Étude morphologique. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Egypte, 30, 97 - 235.

- Vaumas, E. de (1958):

- La structure et le modelé de la Bekaa. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Egypte, 31, 5-66.

- Vaumas, E. de (1958):

- Le massif du Djebel Akra. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Egypte, 31,141 - 193.

- Wirth, E. (1958):

- Morphologische und bodenkundliche Beobachtungen in der syrisch-irakischen Wuste. Erdkunde, 12, 26 - 41.

- Wolfart, R. (1967):

- Geologie von Syrien und dem Libanon. Berlin.

- Wright, H. E. Jr. (1962):

- Late Pleistocene geology of coastal Lebanon. Quaternaria, 6, 525 - 539.

- Zeuner, F. E. (1953):

- Das Problem der Pluvialzeiten. Geol. Rundschau, 41, 242 - 253.

|