|

MARK DION'S "CHAMBER

OF CURIOSITIES"

Takayo Iida

In early September 2002, Mark Dion could be seen at the Tsukiji Fish

Market in the busy throng surrounding the fish sellers chopping up freshly

caught tuna. A symbol of Tokyo's huge stomach, Tsukiji Market has a powerful

impact on the visitor. The order and chaos, pace, noise and dynamic movement

of people and goods encapsulate the energy and diversity of Japan's capital

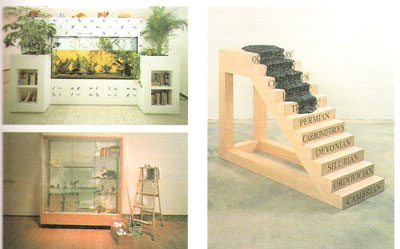

city. Visiting Japan to do field research for this exhibition, Dion was

fascinated by the spectaele. Conceived as a metaphor and symbol of the

Tokyo megalopolis, this project will be conducted in the Koishikawa Annex

of the University Museum of the University of Tokyo. Together with student

volunteers, the artist will collect the unique "garbage"generated in the

"magnetic field" of the campus of the University of Tokyo. The artist

will select items from the vast array of materials and objects, such as

medical specimens, belonging to the University Museum and the university

research laboratories. These objects will then be exhibited together with

the "garbage" under exactly the same conditions. Since the volunteers

and collaborators for this project are students of the university and

teaching staff of the University Museum, the guidance and collaboration

provided by the museum to support the artist's activities will form the

nucleus of the exhibition. This is also a uniquely challenging project

that reveals the chronological phases concealed within these proliferating

objects and the "baroque beauty" that has been obscured by existing values,

while topologically traversing the city of Tokyo within a natural historical

context. The Tsukiji Fish Market, one of the magnetic fields which attracted

Mark Dion when he came to Japan to do field research, is itself a living

system of wonders that reflects Tokyo's dynamism and confusion. If we

view the functions of the city as a metaphor for the human body itself

and Tsukiji as one of its organs, another topological space comes into

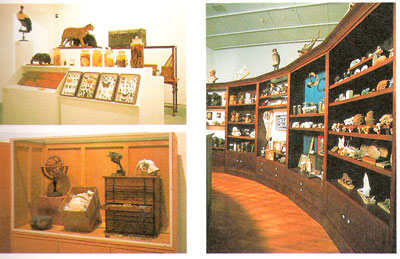

relief. This is the Wunderkammer, the "museum within a museum" set up

for this exhibition. Divided into eight thematic compartments -The Realm

of Air, The Underworld, The Realm of Water, The Terrestrial Realm, Humankind,

Reason and Measure, The Gigantic, and The Miniature -it reflects the many

faces and vital functions of the Tokyo megalopolis.

Mark Dion was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1961 and is currently

based ln New York.lt would be no exaggeration to say that Dion the artist

was a product of the environment of his native New Bedford. New Bedford

boasts the world's biggest whaling museum, containing many exhibits relating

to John Manjiro(1827- 1898), a Japanese fishermen who was rescued by an

American whaling vessel in 1841 and lived in America for 10years. As a

youth growing up in New Bedford, Diorn visited the whaling museum and

industrial museum many times and drew much inspiration from them. Collecting

shells was one of his boyhood passions. Needless to say, these early experiences

form the foundations of his current activities as an artist. For one year

from 1984, Dion studied under the independent Study Program at the Whitney

Museum of American Art, which has produced many of America's leading contemporary

artists. While working as an assistant to Ashley Bickerton, he had the

opportunity to coolly observe the contemporary art scene. In 1987, he

took part in the Dokumenta 8 international exhibition in Kassel, Germany.

Since 1990 he has done various fieldwork relating to environmental problems,

and his art works are usually the results of this fieldwork. He has given

exhibitions in Holland, Germany, France and Eastern Europe, where he has

completed many projects while conducting field research together with

local environmental conservation groups and volunteers.

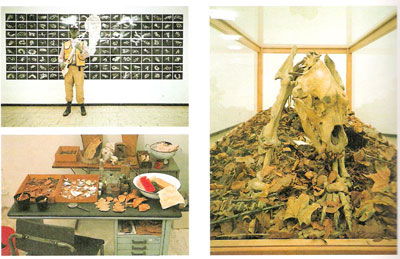

What is the wellspring of Mark Dion's diverse creative activities ? In

order to determine the origin and background of the underlying philosophy

and methodology of Dion's projects, I will here attempt to throw light

on the unique creativity of his works, with reference to the artists who

have had a particularly strong influence on him. These artists include

Joseph Beuysz who produced works in a wide variety of genres, such as

paintings, installations and performances on the theme of "art and socIety,

"merging the conflict between ecology and environmental problems into

folk mythology; Robert Smithson, a pioneer of the genres of Earthwork

and Land Art who explored from the standpoint of entropy the principles

underlying dualisms such as "order and chaos" and "nature and artifice";

Joseph Cornell, who created various microcosmoses through collages of

celestial maps, constellations and musical scores using a box format as

his medium of expression; and Gordon Matta-Clark, who literally deconstructed

abandoned architectural structures to create new spaces. Mark Dion himself

has stated that the above artists, sadly no longer with us, had the greatest

influence not only on his works but on the way he lived. Among currently

active artists, Hans Haake, Tom Burr Ericson & Ziegler, and Jason Simon

have strong philosophical affinities with Dion, while Alexis Rockman,

Gregory Crewdson and Bob Braine share the same methodological approach.

Mark Dion has even arranged these various contemporary artists in one

of his own Wunderkammer, a "treasure chest" of the people that have inspired

his work. In this Wunderkammer the artist freely transcends time frames,

expressing history in the form of a loop rather than the linear succession

of past, present and future. The Hapsburg emperors from the sixteenth

to the seventeenth centuries -Ferdinand l, Maximilian ll, Grand Duke Ferdinand

and Rudolf ll -were all avid collectors. The display rooms they had built

in their palaces were museums known as Kunst- und Wunderkammern in which

they collected objects of "wonderand bizarre beauty." This is the origin

of the word Wunderkammer, the title of this exhibition. The contents of

the Wunderkammer are described by Tatsuhiko Shibusawa in his book Cosmographia

Fantastica: "This museum in the shape of a terrifying devil's mask contained

all kinds of mysterious objects collected from all over the world, arranged

within a very small space. The exhibits included strangely-shaped glass

vessels, jewel jars, tiny sculptures made of ebony, alabaster or serpentine,

ancient musical instruments, mechanical dolls, mummified animals, ancient

animal bones, deformed creatures pickled in alcohol, weird plants, shells

from the South Seas, mineral specimens, optical instruments, celestial

globes, suits of armor, books on witchcraft prayer books, musical boxes,

pisotols, skulls, and so on."

Mark Dion has his doubts about the conventional approach of museums.

The museum has not escaped the influence of the modernist thought that

has permeated society at every level since the eighteenth century. The

objects that filled the Wunderkammer-style museums, which inspired feelings

of curiosity and excitement in the viewer, were rapidly classified and

put in order, to the extent that museums also came to be viewed as "graveyards."

In the field of contemporary art, public art museums struggling due to

lack of funds tried to attract visitors by setting up easy-to understand

exhibition programs that treated viewers like children. In this way, museums

are ceasing to be spaces for programs and modes of expression that draw

attention to various social problems and question the significance of

art. In short, the art museum seems to be turning into a kind of "leisureland."

According to Dion, "A museurn should provoke questions, not spoon-feed

answers and experiences. I'm excited by the tension between entertainment

and education in the idea of the marvelous, especially in pre-Enghtenment

collections like curiosity cabinets and Wunderkammers."

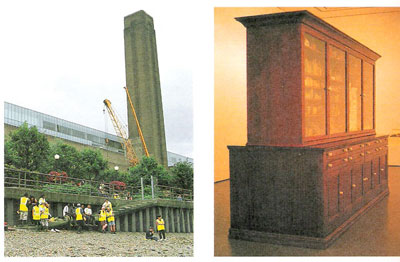

In 1999, Mark Dion conducted a project called the "Tate Thames Dig" by

the River Thames in London together with volunteers, most of them teenagers

from the local community. In this project, the participants applied an

archeological approach to pieces of garbage washed up by the tide or thrown

away on the banks of the river, excavating, cleaning and then classifying

them. The objects thus classified ranged from bones of animals, sea shells,

driftwood, pottery and glass bottles to debris of the consumer society

such as mobile phones, credit cards and microchips. These "chronological

layers" dating back to before the twentieth century were exhibited at

the Tate Gallery. They represented an intriguing reversal of values: the

"garbage" that had accumulated over the centuries had become "treasure,'

while formerly valuable waste products consumed by contemporary society

had turned into garbage! Collaborating with researchers from fields such

as history, cultural anthropology, scence and biology. Dion has made these

projects into his works through fieldwork, workshops and lectures on the

relationship between cities and nature, focusing on themes such as the

relationship between modern cities and ecology, the extinction of species

through environmental pollution and destruction and the question of evolution/

devolution. Through this work, he has gained an international reputation

not only as an artist but also as a social activist. By transcending his

idenntity as an artist, Dion has made art accessible to a wide variety

of people with the ultimate aim of stimulating the revitalization of the

urban community from the perspectives of history and sociology.

Locatingthe origins of the museum in the border region between art and

natural science, Mark Dion has in effect pursued his work as an artist

while devlating from the genre of contemporary art. An exhibition of his

work is therefore replete with possibilities for discovering new appeal

and vitality not only in the museum but also in the role that art can

play in society. Urban-concentrated mass consumer society has now reached

a critical point where we are saturated with simulacra with no relation

to reality and a swelling flood of information disseminated by the Internet

under the banner of globalization. Mark Dion owns neither a computer nor

a mobile phone. Rather than simply rejecting virtual networks, however,

he is reminding us of the importance of stepping back from values of contemporary

society such as speed, precision and virtual reality and devoting ourselves

to the reassessment of these values. Through this "archaeology of knowledge,"

he is attempting to give us a glimpse of a model for future society.

(Exhibition Curator)

|