Architecture Created Through Dialogue

Take Part Process Workshop and Open System Architecture

Individuals, however, do not like to have their freedom restricted. We therefore need to materialize architecture as a system that embodies fluctuations or an open space that has the potential for reciprocity in the relativity of various elements in architecture. In other words, we need to serve as arbitrators to determine the degree of closeness or openness of the relativity, or the margin of fluctuations and tolerance. The results of this process are manifested in the form of architecture.

A society is a constantly changing living organism that often defies our understanding. The society, I believe, is calling for architects to function as arbitrators who dwell in dialogues with society. Architecture for me is nothing but an act of creatively structuring the relativity in real society.

Architecture, a product of the process of dialogue, then begins to grow after its completion and occupancy, this time through dialogue with the society. The interactive architecture, which I am currently working on, is one that is created from such dialogue and one that creates dialogue.

Public architecture is meant to function as a center in one way or the other that responds to the needs of the city or its citizens. Citizens' needs as grasped by the government at a certain point, however, would inevitably change with the passage of time. In that sense, an effective way to create community-based public architecture would be to provide an opportunity for direct talks between the administrative section and citizens at the planning stage, and involve citizens in the center's management after its completion.

Public architecture is meant to function as a center in one way or the other that responds to the needs of the city or its citizens. Citizens' needs as grasped by the government at a certain point, however, would inevitably change with the passage of time. In that sense, an effective way to create community-based public architecture would be to provide an opportunity for direct talks between the administrative section and citizens at the planning stage, and involve citizens in the center's management after its completion.Citizens' participation must be introduced in an appropriate manner at the right stage. Also, catering to all the requests by individual citizens would not necessarily produce good results. We are called on to find away to realize an interactive dialogue among citizens, government representatives and experts that goes beyond coercive governmental action or one-sided demands by citizens.

Moreover, citizens' participation, I believe, nurtures a sense of involvement in and affection for public facilities on the part of citizens. It also helps add a touch of originality to each public facility. Architecture completed in this fashion would continue to grow on the basis of dialogue with the society, and function as material and moral power behind the overall town planning.

As a means to create architecture through dialogue with citizens, I have employed the techniques used in the "Take Part Process Workshop Based on the RSVP Cycle" advocated by Lawrence Halprin. With this method, an exchange of opinion with citizens is carried out at each stage of the project. The process of the project implementation is disclosed to the public so that the work would proceed following the consent of citizens.

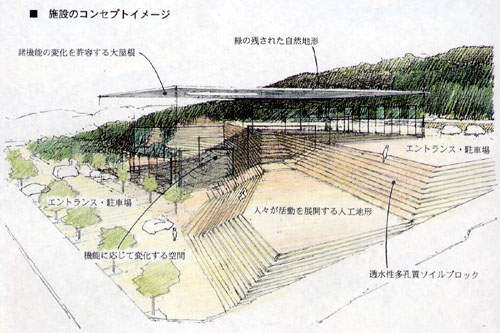

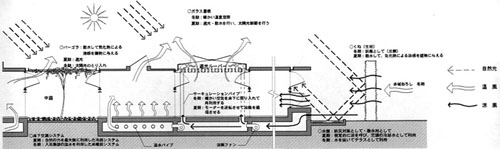

In the area of architecture as hardware, I am seeking to create an Open System Architecture: variable-type architecture that tolerates diversity and flexibility of space so that it will have the leeway to change and grow in response to dialogues with the society. The Open System Architecture is based on a harmonious relationship with the natural environment that blends with the local climate, geography and siting conditions. This system of architecture employs passive environmental technology to reduce the pressure on the environment.

In the area of architecture as hardware, I am seeking to create an Open System Architecture: variable-type architecture that tolerates diversity and flexibility of space so that it will have the leeway to change and grow in response to dialogues with the society. The Open System Architecture is based on a harmonious relationship with the natural environment that blends with the local climate, geography and siting conditions. This system of architecture employs passive environmental technology to reduce the pressure on the environment.

In this project, before drawing up the preliminary plan, we held a workshop for some 1,400 people - pupils, teachers and parents who will be the users of this school - to collect ideas on the project. After compiling and sorting out the presented ideas, and prior to preparing working drawings, we hosted the Shiroishi Design Forum in which we explained participating citizens the outline of the project and exchanged views for better understanding on the course of town planning. At present, after the completion of the school, we hold workshops involving teachers to explore the potential for more effective uses of the school.

In the actual design process, we aimed at creating an open school on the basis of the following basic guideline:

|

|

|

|

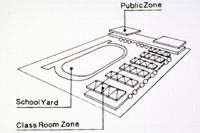

The school wing and public wing are arranged in an L-shape format: a gymnasium that doubles as entrance hall and auditorium is located at the intersecting part between the two wings. This layout effectively blocks out the cold winter winds blowing from Zao mountains and provides sunny spots on the playground. To make the school open to the city, we chose not to erect a wall but to provide a path lined with cherry blossom trees open to ail people.

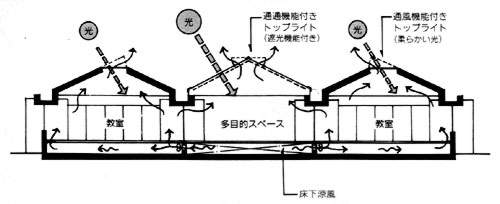

As regards environmental planning, the school was designed to effectively utilize passive energy as much as possible as a positive step toward creating harmony with the environment. The basic elements in promoting environmental technology are; wind, water, light and greenery, among others. In addition to general considerations for ventilation and daylighting, we employed the Korean-type floor heating system for winter. In summer, the cold air beneath the floor helps cool the structure.

Other techniques in environmental technology have been employed in the overall plan. For instance, we built a stream at the side of the public wing to function as a flowing snow ditch in winter, and installed pipe speakers to produce an audio environment that closely resembles the natural environment.

In this primary school project, citizens' participation has been an important factor in overcoming conventional systems and designing a school that is different from the standard plan.

In both works, I presented architecture as suggestions that embody open systems as shown below:

|

The site for the Fukushima General Women's Center is located in Nihonmatsu city, which is positioned at the center of Fukushima Prefecture.

|

|

The site for the Fukushima General Women's Center is located in Nihonmatsu city, which is positioned at the center of Fukushima Prefecture.

The region, embraced by Mt. Adatara and Abukuma River, is not far from the house of Chieko Takamura, a symbolic female figure from Fukushima.

Upon construction, this center was designed to serve as a base for activities along the local government's Fukushima Women's Plan for the New Century. Drawn up in 1994, the Plan seeks to create a society based on equal participation (in which men and women support each other) where all citizens in the prefecture are able to lead fulfilling life by making the most of their abilities and originality.

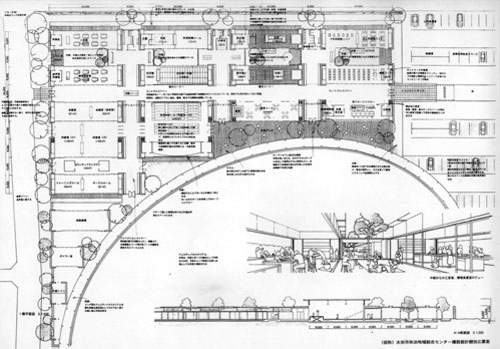

As for the center's design, the flat area along the road in the north and another flat area in the west 12 meters above were set aside for a parking lot and entrance. All rooms are arranged along the topography of the land and joined by an artificial topographical stairs. Mt. Adatara can be viewed from the promenade, great stairs and rooms with an open atmosphere. Each of the four-layer floors are joined by elevators for senior and handicapped persons.

|

This Center also is a suggestion to create a pleasant community-based environment.

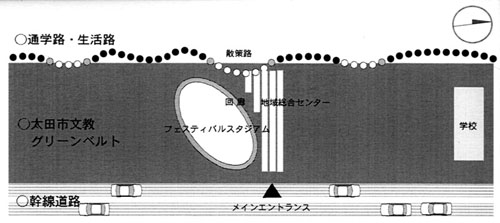

The basic policy concerning site planning is to encourage the greening of the area between the main road in the east and the schooling road in the west, and to foster the formation of an 'educational green belt' around the Center. The space surrounded by corridors is named 'Festival Stadium', which will be the focus of citizens' activities and exchanges to host sport events, flea markets and other events. To protect the outdoor space from fierce winter winds, the building was positioned on the northern side and planting of trees to block the wind was suggested. The idea behind the design is normalization and barrier-free architecture. Based on this idea, all parts of the building are of single-story to provide free and direct access from different spaces to the courtyard or to the outdoor space on the ground level. The movable partition system and function units enable the extension or reduction of spatial units and flexible changes in functions.

Considerations for the local climate and environment include the active use of underground water and vegetation as well as suggestions from people to create a pleasant environment. An intelligent roof was used to let the natural light in, control the input and output of air and heat, and utilize hot water heated by solar energy.

|

|

|