PART II

PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY: THE PEOPLE OF JAPAN PAST AND PRESENT

Isolate Conservatism and Hybridization in the Population History of Japan: The Evidence of Nonmetric Cranial Traits

|

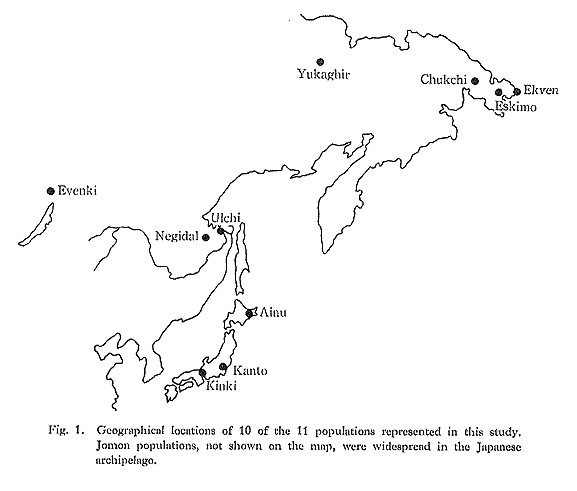

Nancy S. Ossenberg The Jomon culture of Japan, the oldest known pottery-making culture in the world, began about 10,000 years ago and existed undisturbed for more than seven millennia. At about 300 B.C., immigrants from the mainland brought weaving, metalworking, and rice agriculture to Japan, initiating a series of radical changes during the Yayoi period which led to the formation of historic Japanese culture. By 300 A.D., Jomon culture south of Hokkaido had been so completely submerged by these new developments that any subsequent traces have been elusive. Defining the Jomon contribution to Japan culturally, linguistically, and genetically thus constitutes a major problem in Japanese prehistory (Chard,1974). Jomon skulls and limb bones closely resemble the Upper Pleistocene Liujiang fossils of Kwangsi, south China, which represent a stock that had barely begun to differentiate along the Mongoloid line (Yamaguchi, 1982). The Ainu, long an enigma in racial history and systematics, are now recognized as a. remnant population descended from the Jomon, which survived in Hokkaido following ancient hunting-fishing lifeways in relative isolation from post-Jomon influences until the end of the last century. Comparisons based on cranial measurements (Howells, 1966; Yamaguchi, 1982; Dodo, 1982) nonmetric cranial traits (Yamaguchi, 1967) and teeth (Turner, 1976; 1979; Turner and Hanihara, 1977; Brace and Nagai, 1982) attest to the affiliation of Ainu with Jomon. Considerably more controversy centers on the question of the Jomon genetic contribution to the modern Japanese population. Present day gradients southwest to northeast across the archipelago in somatometric characters, ABO gene frequencies, and fingerprint patterns are interpreted as resulting from ancient hybridization (Yamaguchi, 1980; Hanihara, Kouchi, and Koizumi, 1982). This explanation needs to be buttressed by diachronic comparisons, but so far the evidence from such comparisons has been inconclusive. According to Suzuki's reconstruction (1969), Jomon people were ancestral to both Ainu and Japanese. Divergence between the descendant populations was caused by environmental differences, chiefly dietary. On the other hand Turner (1976), stressing the dichotomy between the simple proto Mongoloid tooth morphology characteristic of Jomon-Ainu and the more robust, complicated teeth of modern Japanese and 1000 B.C. Shang Dynasty Chinese, argues that the modern Japanese could easily be the direct descendants of neo-Mongoloid immigrants (i.e., Yayoi folk) from north China. He sees in the dental data some indication that miscege nation could have occurred between the immigrants and aboriginal Jomon people, but judges this to be insignificant. Likewise, skull measurements indicate close resemblance of modern Japanese to 3000-5000 B.C. Neolithic populations of north China (Yamaguchi, 1982) and little resemblance to Jomon (Yamaguchi, 1982; Howells, 1966). However uncertainty as to the size of the colonizing delegations plus cultural and physical evidence from the Yayoi period showing continuity of the aboriginal population (Chard, 1974; Yamaguchi, 1977, 1982) caution that the scheme Jomon → Ainu may be oversimplified. To address the question of indigene-immigrant hybridization the present study examined discrete (nonmetric) variation of the skull. Discrete traits are predominantly under genetic control and, having proved useful for investigating microevolutionary mechanisms at the infraspecific level in various other animals, are becoming increasingly important in research into ethnic continuities (Berry, 1979). Recent reports give nonmetric trait data for various early and modern samples from Japan (Yamaguchi, 1967, 1977; Dodo, 1974, 1975, 1981; Mouri, 1976; Hanihara, 1981). Most of the multivariate distance analyses in those reports are concerned with post-Jomon comparisons within Japan. The present study extends the comparative framework to include Jomon, as well as several cranial series representing neo-Mongoloid populations of continental northeast Asia, in order to address the question of the Jomon people's genetic contribution to the modern population of Japan. Materials and MethodsCranial series providing data for this study include four from Japan and seven from Siberia. No skeletal series from Korea was available for study. Locations of the populations are mapped in Fig. 1, and sample sizes are given in Table 2.

Late phase Jomon (ca. 3000-500 B.C.) skeletal remains, mostly from the Tsukumo site in western Honshu, are housed in the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology at Kyoto University. A few remains from other Honshu sites were studied at the National Science Museum in Tokyo. The Ainu skeletal sample represents a nineteenth century population from central and northeast Hokkaido, and is claimed to be the least influenced by Wajin (modern Japanese) mixture of any available sample (Yamaguchi, 1967). Collected by the late Professor Y. Koganei, the skeletons are housed in the University Museum of the University of Tokyo. Recent Japanese crania are from dissecting room subjects. Those from the Kanto district are housed in the University Museum at the University of Tokyo; those from the Kinki district are in the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology at Kyoto University. Material from the ancient Eskimo cemetery of Ekven, B.C./A.D.-A.D. 200, was studied in the Laboratory for Plastic Reconstruction of the USSR Institute of Ethnography, Moscow. Six other Siberian samples represent recent populations and are housed in the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology of the USSR Institute of Ethnography, Leningrad. All these Siberian peoples are of neo-Mongoloid racial type (Alexseev, 1979). Twenty-six discrete cranial traits employed in this study arc listed in Table 1, according to four categories: hypostotic traits, hyperostotic traits, features related to variations in nerves and blood vessels, and variations at the craniovertebral border. Table 1 gives their frequencies in the four samples from Japan, sexes and sides pooled. All data were recorded by the author.

Previous reports provide descriptions of the individual features, methods for their scoring and statistical analysis, and evidence that this particular battery yields valid taxonomic information; i.e., distance measures congruent with those based on other data sets (craniometric, genetic marker) and/or congruent with known relationships (Ossenberg, 1969, 1970, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1981; Szathmary and Ossenberg, 1978). The distance measure used is a modification of C.A.B. Smith's Mean Measure of Divergence (MMD), using the Freeman-Tukey inverse sine transformation of trait frequencies (Sjovold, 1977). Cluster analysis produced a dendrograph of the 11 samples (McCammon and Wenninger, 1970). A Chi-square approximation derived from the individual term of the MMD (Sjovold, 1977) was used to test for significance of frequency difference of each trait between Jomon-Ainu, Jomon-Japanese (pooled), and Ainu-Japanese (pooled). ResultsOf the 26 traits studied, 19 showed significant differences (p<.10) in one or more of the comparisons within Japan (Table 1). Highly significant differences (p<.001) were found for 13 traits: os japonicum trace, infraorbital suture, tympanic dehiscence, M3 suppressed, pterygobasal bridge, trochlear spur, mylohyoid bridge, auditory exostoses, supraorbital foramen, postcondylar canal absent, hypoglossal canal bridged, pharyngeal fossa, and odonto-occipital articulation. These traits represent all parts of the skull (vault, base, and face) and each of the four trait categories (hypostotic, etc.).1 The figures in Table 1 indicate Jomon and Ainu are similar to each other, and that Kanto and Kinki are even more so. For those traits in which they differ significantly from Jomon, Ainu tend to be intermediate between Jomon and modern Japanese. These relationships are illustrated in Fig. 2, where the total morphological pattern of each population is depicted as a polygon based on 18 of the features. Emerging from these diagrams is a relationship not readily discerned in Table 1; namely, that Kanto Japanese tend to be intermediate between Kinki Japanese and Ainu. Thus the polygons form a graded series: Kinki-Kanto-Ainu-Jomon.

Mean Measures of Divergence (Table 2) based on the 26-trait battery quantify population relationships. Six MMDs for within-Japan comparisons (upper left triangular area of the table) are wholly consistent with the gradation of profiles in Fig. 2, being ranked as follows:

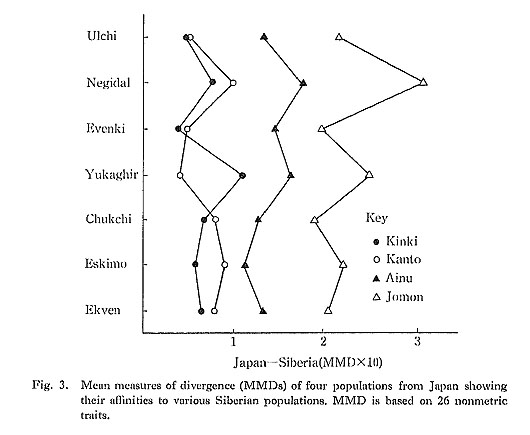

Within-Japan MMDs were compared to within-Siberia MMDs (lower right triangular area of Table 2). Chukchi form a cluster with recent and ancient Eskimo; Tungus (Ulchi, Negidal, Evenki) form a second one. Within these clusters most relationships (MMD range 3.8-47.3) are closer than Jomon-Ainu (47.9) and Kinki-Kanto (33.9). At the other extreme, distances as large as Jomon-Japanese were found between Yukaghir and Chukchi-Eskimo. In the intermediate range and comparable to Ainu-Japanese are the affinities between Tungus and Chukchi-Eskimo and between Tungus and Yukaghir. Such comparisons help place the within-Japan MMDs in perspective. Siberia-Japan MMDs are in the rectangular area of Table 2 and are graphed in Fig. 3. These were examined (i.e., reading down Table 2 and down Fig. 3) for each of the four series from Japan to answer the question: are its relationships within Japan closer than its relationships with foreign populations? In this context Jomon and Ainu are "insular," their closest relationships being with each other, followed by modern Japanese. In contrast, modern Japanese, especially the Kinki Japanese, have closer affinities with Siberians than with Ainu or Jomon, Another contrasting feature is that Japanese tend to be closer to Tungus than to Chukchi-Eskimo, whereas Jomon and Ainu show the reverse. As did preceding comparisons, these also point to a dichotomy between Jomon-Ainu and Kanto-Kinki.

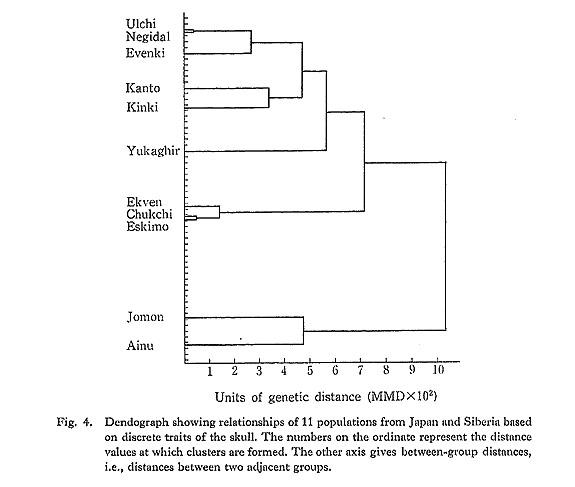

The MMDs for each of the seven Siberian samples were examined (i.e., reading across Table 2 and Fig. 3) to answer the question: to which of the four series from Japan is each sample most closely related? With one exception (Yukaghir's close affinity to Kanto, 38.4), the MMDs rank from smallest to largest: Kinki-Kanto-Ainu-Jomon. In every case the difference between the smallest distance for Kinki (or Kanto) and the largest for Jomon is clear and unequivocal. In graphic summary of the foregoing, the dendrograph (Fig. 4) portrays the dichotomy between recent Japanese on the one hand and Jomon-Ainu on the other. It shows Japanese clustered most closely with Tungus, then at successively higher levels with Yukaghir and Chukchi-Eskimo, while Jomon-Ainu are isolated from all these. The clustering technique, however, obscures important aspects of the relationships; namely, that Ainu are intermediate between Jomon and recent Japanese, Kanto clearly are closer to Jomon-Ainu than are Kinki, and Kinki are closer to Siberians than are Kanto. Interpretation of this gradient is the main theme of the following discussion.

DiscussionThe gradient of biological distances found in this study, Siberians-Kinki-Kanto-Ainu-Jomon, is consistent with the theory that hybridization between Jomon and continental immigrants during Yayoi and succeeding periods played an important role in Japanese population history. The argument is as follows. According to the archaeological record Yayoi culture first appeared about 300 B.C. in north Kyushu. From there it spread eastward to reach the Kinki region by 200 B.C. After passing central Honshu the spread was less vigorous and the basic complex was slightly altered. By about 300 A.D. it had transformed all local cultures south of Hokkaido, Later Yayoi and the succeeding feudal Kofun society, A.D. 300-600, were maintained by cosmopolitan networks linking large centers in Kyushu and western Honshu with each other and with the continent. However, communities in northeastern Honshu remained smaller and somewhat peripheral to these latter developments (Chard, 1974; Ikawa-Smith, 1980). It is proposed that the MMD gradient, paralleling the dispersal of new culture elements, was shaped by regional differences in gene flow such that Kinki are most like continental Asiatics, Kanto are intermediate, and Ainu have retained the largest endowment from Jomon. Whatever the aboriginal population size compared to the number of colonizers at the time of contact, the latter could have had significant regional genetic impact through the population growth rate differential between farmers and hunter-gatherers (Yamaguchi, 1982). Once established, dines would have been perpetuated by sociocultural factors as well as by the mountainous topography of the archipelago; even present day regional variations are thought to relate to narrow ranges of mobility and mate selection throughout the long history of Japan until the 20th century (Kondo and Kobayashi, 1975). While not necessarily implicating admixture, Japanese workers occasionally note dines in their cranial data. Using 14 nonmetric features Dodo (1975) found that distance patterns of four recent Honshu series (Kinki, Kanto, Tohoku, and an earlier 18th-19th century series from the Unko-in Temple) closely correspond to the geographic relations among the samples. Further, his distances for these four from other Asian series hint at a continental extension of the dines, with Tohoku being progressively more distant from Korea, north China, and Mongolia. Nasomalar angle, a measure of upper facial flatness, decreases in recent Japanese from northeast to southwest; i.e., faces are flatter (more Mongoloid) in the southwest. That similar clines are seen in Jomon populations may indicate that such gradients have remote sources even predating the Yayoi immigration (Yamaguchi, 1980). Yamaguchi's (1982) generalized distances (corrected D2) based on eight cranial measurements follow a geographical gradient, with recent samples from northeast to southwest increasing in distance from Jomon as follows:

Moreover, in the regions where diachronic comparisons are made the aboriginal population is closer to the earlier remains (and in temporal order: Yayoi, Medieval, early Modern) than to the most recent ones, in keeping with the idea that admixture was cumulative over time. From Kyushu, dose to the presumed entry point of the mainland immigrants, D2 decreases again to the southwest:

A dose Jomon-Okinawa affinity hints that Okinawana (Ryukyuans) may to some extent represent, as do Ainu, a residual isolate descended from a proto-Mongoloid population with ancestral roots in southeast Asia. In keeping with this idea a close affinity between Ainu and Ryukyuans has been shown with respect to dental morphology (Hanihara et al., 1973) as well as genetic polymorphisms in the blood (Omoto and Misawa, 1976). Beyond Japan, Yamaguchi's comparisons reveal Jomon most distant from northeast Asians: the D2 range for five series is 12.34-19.42. Yamaguchi's craniometric study has only six populations in common with the present nonmetric one. Nevertheless, the perfect rank correlation between MMD and D2 for 10 population comparisons is highly significant (Fig. 5).2 Considering that nonmetric traits have been demonstrated to vary independently of the developmental processes expressed in skull dimensions and that most of the features analyzed show interaction either absent or at a very low level (Dickel, 1980), we may view the evidence from the two data sets as additive support for the argument presented here. Discrete trait data for additional samples are needed in order to fully define geographical and temporal patterns of the MMD.

Cautioning against a too facile interpretation of dines is the finding that Jomon's geographic variability in cranial measurements equals that of modern populations (Howells, 1966; Yamaguchi, 1980; Dodo, 1982). As foreign intrusion is not implicated this early, some mechanism other than admixture must have been involved. Looking back to Suzuki's theory, we must consider the possibility that environmental differences played a role in shaping the pattern of affinities revealed by discrete traits. Gracilization of the limb bones and increasing stature in Yayoi and subsequent periods (Yamaguchi, 1982) together with decrease in face breadth and tooth size (Brace and Nagai, 1982) point to adaptive response as an important factor in Japan, associated particularly with the transition from food gathering to rice agriculture. Theoretically, minor cranial variants being "epigenetic" (i.e., controlled by environmental as well as hereditary factors), they also could be affected by such changes (Berry, 1979). On the other hand there are arguments against an adaptive response interpretation of the pattern of affinities seen in this study. In contrast with skeletal characteristics such as stature, these particular discrete traits appear to be resistant to shifts in ecozone and subsistence economy (Ossenberg, 1976; Szathmary and Ossenberg, 1978). Moreover, there does not seem to be any common environmental factor which would affiliate the Siberiansall hunting-gathering peoples-with recent Japanese rather than with Ainu or Jomon. The consensus of the Siberians' affinity to the Kinki Japanese is all the more remarkable when we consider the diverse environments represented in the enormous area between the Amur Valley and Chukotka Peninsula. Thus, while adaptive response may have contributed, it is likely that gene flow was the main mechanism shaping the MMD gradient in Japan. Reviewing the accumulated evidence of anthropological studies, Hanihara and coworkers (1982) conclude that the geographical variation in cranial shape of modern Japanese was likely caused in large part by hybridization of the aboriginal population with post-Jomon immigrants. The influence of the latter was greatest in the Kinki district and part of western Japan. In agreement with Suzuki, they see this influence to be relatively small in the Kanto district and eastern Japan where Jomon physical characteristics persisted. They suggest that the physical differences between eastern and western Honshu are paralleled by a duality of cultural and environmental characteristics as revealed by archaeology, folklore, and linguistics. The findings in the present study agree with this interpretation, though showing Kanto more than marginally shifted away from Ainu-Jomon and towards Kinki. As far as the Ainu are concerned: the reciprocally close Jomon-Ainu affinity revealed by nonmetric cranial traits, in agreement with other studies, is consistent with the reconstruction that Ainu are descended from Jomon and conserve in their gene pool a major contribution from these ancient ancestors. A question remains concerning mixture in the ancestry of Ainu. Turner (1976), noting that eight of nine Ainu dental features (studied in dental casts of contemporary people) shifted away from Jomon and towards recent Japanese, attributes this to recent gene flow. This interpretation is supported by documentation showing that mixture during historic times was minimal until 1868 when Hokkaido came under Japanese government control (Omoto and Misawa, 1976). However, it is doubtful that mixture so recent could account for the intermediate morphology of nineteenth century Ainu skulls. Their MMD and D2 cranial distances seem to fit better with the interpretation that Ainu represent the northeastern terminus of gradients established by ancient gene flow. The Yayoi colonizers are believed to have come from the region that is now Korea, hough their precise source has yet to be identified. Unfortunately, no skeletal series from Korea were available for analysis. Siberian samples were included in this study, not with the notion that any of them might be specifically related to Yayoi, but simply as general representatives of the classic Mongoloid stock of northeast Asia. Nevertheless some comments on Siberian affinities are in order. Firstly, the Ulchi-Negidal-Evenki cluster and Chukchi-Eskimo-Ekven cluster derived from MMDs correspond, respectively, with the "Baikal" and "Arctic" morphological complexes defined by Soviet researchers on the basis of craniometric, anthropometric, and anthroposcopic analysis (Alexseev, 1979). Further, the position of the Yukaghir sample3 in the MMD dendrograph (Fig. 4) is consistent with the linguistic position of Yukaghir (Black, 1979) and with the view that this tribe represents a remnant of a paleo-Asiatic population once widespread in Siberia cast of Lake Baikal and ancestral to Tungus (Levin, 1963). Such correspondences lend credence to other interpretations of MMDs which rest on the assumption of their validity as estimates of genetic relationship. Secondly, modern Japanese are more closely related to the Tungus (Ulchi-Negidal-Evenki) than to the Chukchi cluster. This is consistent with a putative linguistic affiliation of Japanese with the Tungus tribes through proto-Altaic (Miller, 1971) and is satisfying also in view of the description of the Baikal complex as being distinguished from other Siberian morphological complexes by its maximum development of Mongoloid features (Alexseev, 1979). In conclusion: bones and teeth provide convincing evidence of the Ainu's Jomon ancestry even though 2500 years or more separate the populations sampled. In turn Jomon people, enclaved in the insular environment of the postglacial period, seem to have preserved skeletal characteristics linking them much further back in time to a southeast Asian Upper Pleistocene ancestor scarcely differentiated along the Mongoloid line, even while their contemporaries in northeast Asia already had evolved as classic Mongoloids. Thus, there appear to be exemplified in the population history of Japan both a remarkably tenacious conservatism of skeletal morphology and a well-defined gradient of biological distances produced by gene flow between proto-Mongoloid indigenes and neo-Mongoloid immigrants. This model could have parallels in other parts of Asia, and also could be useful when considering the various sources, dates, and routes of immigrations to the New World (Jennings, 1978). SummaryFrequencies of 26 nonmetric cranial traits reveal modern Kinki district Japanese to be closely similar to the Kanto district population. Compared to these Japanese, Jomon are most dissimilar while Ainu are intermediate. Mean Measures of Divergence (MMD) for these four samples, and seven samples representing Siberian populations, follow a gradient: Siberians-Kinld-Kanto-Ainu-Jomon. In light of the archaeological record the MMD dine in modern Japan is interpreted as resulting from a southwest to northeast differential in gene flow during Yayoi and subsequent periods such that people of western Honshu are more closely descended from continental immigrants while Ainu, isolated in Hokkaido, have retained the largest genetic endowment from Jomon. Endnotes1. My frequencies of os japonicum trace are larger than those reported by Japanese investi gators (Dodo, 1974, 1975, 1981; Hanihara, 1981; Mouri, 1976; Yamaguchi, 1967, 1977) owing to my inclusion of minimal traces in the category "trait present," as consistent with scoring of North American series in which this feature is much less common. The authors cited have not reported certain features in my battery (IS, M3, TS, AOF, PPTS, SPF, MF, LPPF, PBB, ICC, PF), and they include in their trait lists certain features which I do not. For the other traits reported in common our frequencies are generally very close. Although variability in individual features may be of interest from the point of view of possible adaptive or other microevolutionary significance, this topic is beyond the scope of the present paper.[return to the text] 2. D2 values in addition to those published (Yamaguchi, 1982) were kindly sent to the author by Dr. Yamaguchi.[return to the text] 3. The Yukaghir cranial series is of uncertain provenience, as discussed by Alexseev (1979, p. 79) and Levin (1963, footnote p. 187). The possible ascriptions are either Tundra Yukaghir or Chukchi, the latter probably on the basis of the location of the mound from which the burials were excavated (the Markovskiy Rayon of the Chukchi National Okrug). According to Levin, Debets, after considering a number of facts concluded that this series did represent Yukaghirs. The MMD data in the present study appear to support this, as they cluster with Tungus and are not closely related to Chukchi. In any case, the close Kanto-Yukaghir affinity (MMD 38.4, rivalling Kanto-Kinki 33,9) is difficult to explain and may simply be spurious.[return to the text] AcknowledgementsFor their most generous help and hospitality I wish to thank the following: Dr. K. Hanihara, Tokyo University; Dr. B. Yamaguchi, National Science Museum, Tokyo; Drs. J. Ikeda, T. Mouri, and M. Nishida, Kyoto University; Drs. V. Alexseev, T. Kuzmina, V. Paritzkij, A. Pestrjakov, A. Zoubov (Moscow), and A. Kozintsev (Leningrad), of the Institute of Ethnography, Academy of Sciences USSR. Financial support for study of the North American collections derived from the following sources: National Research Council of Canada (doctoral fellowship, 1963-64), Boreal Institute of the University of Alberta (1970), Canada Council (1975-77), and Advisory Research Council, Queen's University (1973-74). Support for study of collections in Japan and the USSR was provided by a 1980-81 leave fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Data analysis was funded during 1981-82 by the Advisory Research Council of Queen's University. References

|