PART I

ARCHAEOLOGY: JOMON HUNTER-GATHERER

SUBSISTENCE AND SETTLEMENT

Regional Variation in Procurement Systems of Jomon Hunter-Gatherers

|

Takeru Akazawa A number of significant differences characterize Jomon groups, both in the process and the results of their acceptance of the rice cultural complex, as shown in various studies (e.g., Kondo, 1962; Kanaseki and Sahara, 1978; Akazawa, 1981, 1982a, b; Koyama, 1983; Sasaki, 1983). Among these differences, the most significant is regional variation in receptivity to rice: the western Jomon people accepted rice smoothly, whereas the several eastern Jomon groups, especially coastal groups, seem to have resisted accepting rice cultivation. Another significant difference can be seen in the succeeding Yayoi cultures. The eastern Yayoi people retained much of the hunting-gathering economy of the preceding Jomon, even after adopting rice cultivation. They showed a strong tendency toward a traditional lifeway based upon the diverse locally flourishing Jomon cultures; this diversity in eastern Yayoi stands in remarkable contrast to the cultural uniformity observed in the early western Yayoi culture. This study investigates the question of why these phenomena arose in Japanese prehistory, through an examination of several Jomon hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. I conclude that regional variation in procurement systems of the Jomon hunter-gatherers gives us a reliable perspective from which to explain divergent paths in the transition to a settled life of agriculture in Japan. This study focuses on the thesis that where the procurement system was more rigidly regulated by the seasonal scheduling demands of two or more major productivities, as in the case of the eastern coastal Jomon societies, agricultural innovation would have been resisted. Before considering Jomon procurement systems, I review the literature on two controversial subjects: (a) Jomon plant husbandry, and (b) Yayoi population. These are closely related to the problem of cultural change from hunting-gathering to rice cultivation in Japanese prehistory. Jomon Plant HusbandryEarly cultivation during the Jomon period has been the subject of considerable discussion in Japanese archaeology and has become one of the primary concerns in the study of Jomon subsistence (e.g., Fujimori, 1970; Nishida, 1983; Rowley-Conwy, 1984). Review- ing these studies, I find that Jomon cultivation hypotheses can be classified into two major categories. The first hypothesis proposes that the Middle Jomon inhabitants of central inland regions of Japan supplemented their diet of collected foods with more stable resources in the form of intensively tended and/or cultivated plants such as millet, potatoes and nuts (e.g., Fujimori, 1970; Nishida, 1983). This hypothesis has been inferred from archaeological contexts and ethnographic records. Most discussion rests primarily on the assumption that increased settlement size and stability, and the elaboration of ceramics, would not have occurred without dietary supplements in the form of cultivated and/or tended plants. Furthermore, other characteristics could also indicate subsistence stability and specialization: 1) numerous chipped axes/adzes, grinding stones, and stone querns; 2) a wide variety of ceramics, some of which may have had ritual and storage functions; 3) clay female figurines and stone batons with sculptured heads. Nevertheless, we are still reluctant to accept the existence of Middle Jomon cultivation based only on this kind of indirect evidence. The second hypothesis concerns the possibility of cultivation in the later Jomon period, before the arrival of rice cultivation from continental Asia. Botanical ecologists say that western Japan is situated at the northern end of the laurel forest zone characterizing southeast Asia, in which a swidden-type agriculture is widely distributed. Therefore, it is probable that the same type of agriculture could have diffused to western Japan during the Jomon period and been pursued by the inhabitants of this region (e.g., Nakao, 1966; Ucyama, 1969; Ueyama et al,, 1976; Sasaki, 1971, 1982). They propose that a subsistence economy of this kind occupies an intermediate position between hunting-gathering and rice agriculture in Japan. These functional interpretations have broadened our view of the possibilities of Jomon subsistence and also of the transition to rice agriculture in Japan, but they have not been proved archaeologically. Research methods and analytical techniques applied to several categories of archaeological materials, particularly faunal and floral remains, have recently become very sophisticated and are now contributing significantly to the study of Jomon subsistence. Under these circumstances, Jomon cultivation has recently been discussed using more direct evidence, i.e., plant remains in the form of pollens, plant opals, and other features such as seeds. Thus, gourd (Lagenaria sp.), gram or Asian bean (Phaseolus sp.), perilla (Perilla sp.), and paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera) have been identified. This suggests that some plant species were cultivated by certain Jomon hunter-gatherers, although it is not certain to what extent the cultivation of these species was a part of Jomon procurement systems. Nishida (1983: 306) states, from nutritional studies of cultivated plant species identified in the Jomon deposits, that their contribution to the total diet of the Jomon people was not significant. The available data indicate that the majority of Jomon subsistence was provided by wild resources, even though it might have been to some extent supplemented by cultivated plants. Yayoi PopulationIn light of recent research, it has been concluded that the beginning of rice cultivation in Japan was stimulated by influences from the continent during the Jomon period (e.g., Yamazaki, 1979, 1982; Nakajima, 1982). However, the problem of whether the transition to a rice culture occurred as a result of immigration or as a result of adoption by local Jomon groups is still a controversial subject in Japanese prehistory. A number of scholars in the field of physical anthropology have supported a hybridization theory (e.g., Kiyono, 1938, 1949; Kohama, 1960; Turner, 1976; Kanaseki, 1976; Omoto, 1978; Yamaguchi, 1982; Brace and Nagai, 1982; Hanihara, 1983, 1985). These studies all proposed, with some differences in the analytical data, that the Japanese population was formed by an admixture of two major populations: the indigenous Jomon people and immigrants from the continent. For example, Kanaseki (1976) concluded from the analysis of human skeletal remains found in the Kyushu and Chugoku districts that the Yayoi population in western Japan was composed of descendants of the indigenous Jomon people and immigrants from the continent who brought rice culture to the Japanese archipelago. Hanihara (1983, 1985) has recently theorized a similar view that in western Japan an admixture of immigrants with the Jomon people took place during the Yayoi and/or succeeding periods. Moreover, he concluded from a multivariate analysis of human skeletal measurements of Jomon, Yayoi, and other relevant Asian populations as follows: The populations which migrated to the Japanese islands from the Asian continent via the Korean Peninsula during the Yayoi and protohistoric ages made n very large impact on the Jomon people, especially on those who lived in western Japan. The geographical variations in modern Japanese [Hanihara et. al., 1982] probably are caused by different amounts of admixture between the Jomon people and these migrants (Hanihara, 1985: 109-110). Hanihara (1985: 110) also states that "microevolutionary changes should be taken into consideration in addition to the effects of admixture." Nevertheless, he proposes that the hypothesis that immigrant groups from northeastern Asia significantly affected the indigenous Japanese gene pool can explain the data available reasonably well. Another plausible hypothesis, a transformation theory, has been formulated by H. Suzuki (e.g., 1956, 1969, 1981, 1983). Suzuki bases his conclusions on extensive studies of a long series of Japanese skeletal remains dating from the Pleistocene to the present. His view is that if repeated waves of immigrants occurred during the Yayoi and subsequent periods, the immigrants were not numerous enough to significantly affect the thenexisting Japanese gene pool. He believes that changes over time, and regional differentiation in physical characteristics observed for the Japanese, occurred mainly due to the manenvironmental relationship, especially to diversity in nutritional and dietary patterns, and not because, of an admixture with immigrants. Suzuki's hypothesis is supported by the recent work of Kouchi (1983 and also Chapter 5 of this volume). Kouchi discusses reasons for physical changes over time which took place in only twenty years, or one generation, basing her work on somatometric data from modern Japan. She concludes that some physical traits such as the cephalic index, which had been considered reliable racial characteristics, are highly unstable in certain circumstances. She also states that dietary patterns are one of the most important factors responsible for changes of these physical traits over time. In order to evaluate Suzuki's transformation theory and Kouchi's analytical results from an archaeological viewpoint, evidence concerning Jomon subsistence activities is needed. In this paper I will discuss regional diversity in the Jomon hunter-gatherer response to rice cultivation by proposing a hypothetical model of the distribution of differing Jomon procurement systems. Regional Differences in Jomon Hunter-Gatherer AdaptationA number of different approaches have been taken to explain regional differences in hunter-gatherer adaptation. The most popular method to date in the field of Japanese prehistory has been to study the distribution of local pottery-making traditions. In this study, however, stone tools and fishing gear are the basis of comparison. Groupings of these tools are derived from discriminant function analysis, and the adaptation patterns at various localities are postulated from the inferred functions of the artifacts. Tool-kits of Jomon Hunter-GatherersFirst, it is necessary to summarize the results of site clustering by discriminant function analyses of two kinds of Jomon tool-kits, lithic (Akazawa, 1982a; Akazawa and Maeyama, n.d.) and fishing (Akazawa, n.d.a.). Approximately 200 sites representing the later Jomon period, ca. 2500 to 300 B.C., can be discriminated into four homogeneous groups using weighted combinations of the original variables. Each group of sites discriminated by the same pattern of gathering-hunting-fishing equipment also displays a similar geographical distribution, that is, a geographical clustering (Table 1, Fig. 1).

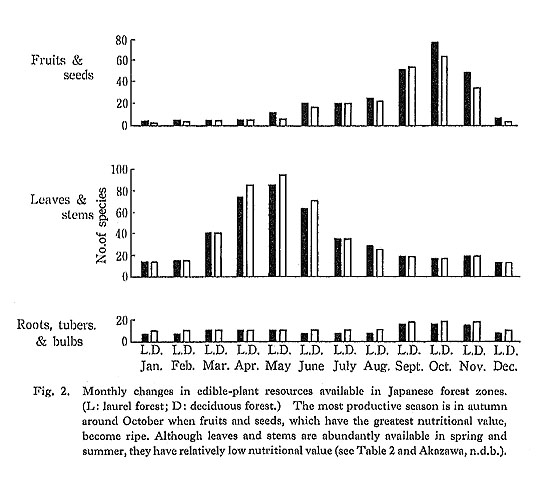

Western Jomon sites are distinguished from other site groups by a weighted combination of six artifact types: stone querns, grinding slabs, grinding stones, chipped stone axes, and two types of stone sinkers. The analysis particularly stressed the discriminatory power of the chippcd stone axe and stone sinkers. Frequency of these tools shows a high positive correlation within this site group, while a series of fishing equipment made from bone and antler material shows a high negative correlation. Eastern Jomon sites are divided into three geographical clusters based upon the well- defined discriminations seen in Table 1. The most distinctive characteristic of the coastal site cluster from northern Japan-that is from Hokkaido and the Pacific coast of the Tohoku district-is a tool-kit composed of a great variety of artifact types. This site cluster is separated from others by the discriminatory power of stemmed scrapers, stone awls, flake scrapers, open and closed toggle harpoon heads, and one-piece anchor and composite fishhooks. In particular, the analysis stressed the discriminating variable of the toggle harpoon heads. A second cluster of eastern Jomon sites is distributed in the coastal lowlands of the Kanto and Tokai districts of central Japan. It is separated from. the other clusters by the discriminatory power of stone projectile points, polished stone axes, and reused potsherd and grooved pottery sinkers. The frequencies of reused potsherd sinkers and projectile points show a particularly positive correlation in this site cluster. In addition, the tool-kit of this site group, as inferred from archaeological research to date (e.g., Kaneko, 1971; Watanabe, 1973), includes bone and antler spear heads in significant proportions. The final cluster of eastern Jomon sites, which is distributed in the interior and along the Japan Sea coast of eastern Japan, is distinguished by an intermediate combination of variables from the western and eastern clusters. Indeed, this site group is discriminated by projectile points and two types of stone sinkers, which are discriminators for the eastern coastal sites of the Kanto and Tokai districts and the western sites, respectively. Exploitation Territories of Jomon Hunter-GatherersBased upon the well-defined discriminations outlined above, we can postulate a strong possibility that specific tool-kits were developed in different areas. Furthermore, if intersite artifact variability was due to differences in activity in different environments, it seems probable that all sites in, a cluster defined by identical tool-kits underwent a similar process of adaptation to the environment. In order to evaluate this postulate about the significance of area-specific interassemblage variabilities in Jomon societies, it is necessary to learn more about the environmental conditions of the exploited areas in which these tool-kits were utilized. In delineating different territorial models for these four site clusters, it should be remarked that geographical analysis of most of the Jomon shell-midden sites discussed here shows that they were located in transitional zones between two or more diverse environments, for example, between mountainous forest and maritime settings. Based upon location patterns of this kind as well as deposits at the sites, the following three types of exploitation territories are discernible: a combined forest-freshwater ecosystem, a combined forest-estuary ecosystem, and a combined forest-Pacific littoral ecosystem (see also Akazawa, n.d.b.). Combined Forest-Freshwater EcosystemExploitation territories utilizing this type of ecosystem are characteristic of the site clusters of western and inland eastern Japan. In western Japan, these sites are situated in transitional zones between freshwater rivers or streams, marshes or lakes, and mountainous laurel forests. In eastern Japan they occupy similar settings within the deciduous forests. The tool-kits found in the western cluster stress the exploitation of plant resources and freshwater fish species from the two ecosystems mentioned above. Chipped stone axes, the most significant variable discriminating this site cluster, are generally considered to have been used as harvesting tools for plant resources such as roots, bulbs, and tubers (e.g., M. Suzuki, 1981; Kobayashi, 1983). It is noteworthy that this tool is significantly connected with stone querns and grinding stones in this cluster's tool-kit, which are also described as plant processing tools (e.g., Watanabe, 1969; M. Suzuki, 1981; Kobayashi, 1983). Stone sinkers, the other significant constituent in the tool-kit of this cluster, were possibly used for freshwater net fishing (Watanabe, 1973). The tool-kit found in the inland site cluster of eastern Japan is different from that found in the western cluster, although the ecosystems of the two areas were similar. That is, the eastern site cluster does not exhibit a high positive weighting of chipped stone axes and other stone tools related to plant resource exploitation, as does the western cluster. Projectile points, which are the most significant discriminating variable of the eastern inland cluster, were a hunting tool for land game in deciduous forests and/or equipment for freshwater fishing. Stone sinkers, also a significant variable, were possibly used during net fishing in freshwater. Combined Forest-Estuary EcosystemGeographic conditions inducing this type of ecosystem occurred in the coastal regions of the Kanto and Tokai districts of eastern Japan. This region is characterized by flat diluvial uplands, with alluvial lowlands along the coast. In particular, it should be pointed out that a great many shell middens and other types of occupation sites were formed during the early- and mid-Holocenc marine transgression in these coastal regions. At this time great embayments, surrounded by much longer coastlines, existed. These cmbayments were generally formed far inland, with no direct influence from oceanic currents. The head of Tokyo Bay, for example, lay some forty kilometers inland from its present position. Rivers also flowed into the bays, contributing to the creation of estuarine ecosystems (Akazawa, 1980, 1982b, n.d.a.). The tool-kit of this site cluster is closely related to fishing activities in embayment conditions. Pottery sinkers, which are most significantly correlated with this site cluster, were possibly developed through, net fishing for estuarine species and maritime species which migrated seasonally into the bays. Projectile points and spear heads, which are also significantly positive discriminators for this site cluster, could have been used to exploit maritime species as well as land game. Combined Forest-Pacific Shelf Littoral EcosystemExploitation territories combining forest and littoral ecological zones were inhabited by northern Jomon people in Hokkaido and the Tohoku coastal district. This site cluster is, like that of the Kanto and Tokai districts, characterized by a high density of extensive shell middens. However, estuaries were not a major geographical factor, as here the mountains rise fairly abruptly from the sea without a coastal plain. Geomorphological evidence from site surroundings, as well as the marine species assemblages found in the midden deposits, have contributed to this conclusion (e.g., Watanabe, 1973; Akazawa, 1982b, n.d.a.). That is to say, the process of adaptation to a maritime environment within this site cluster was not significantly affected by the mid-Holocene transgression that elsewhere created extensive estuarine settings. This group was well adapted to the open ocean environment and its resource potential. Its most important resource was various large species of fish, such as tuna (Thunnus sp.) and bonito (Katsuwonus sp.), that migrate seasonally to the coastal area of this region. Other major marine resources were a number of sea mammals in Hokkaido and a variety of coastal fish species which widely inhabit the rocky-shore zones of this region. Under these circumstances, a great variety of fishing equipment evolved, as illustrated in the results of the discriminant function analyses. Toggle harpoon heads, with a highly significant intragroup correlation, are considered to have been used in fishing for migratory species and for hunting sea mammals on the continental shelf littoral. Other equipment, including various fishhooks, suggests that different fishing methods were used in taking the rocky-shore species of this region, which constitute the largest proportion of faunal remains in the deposits. Stemmed scrapers, awls, and flake scrapers, which are significant variables discriminating this site cluster, are all non-primary tools (e.g., Kusumoto, 1973; M. Suzuki, 1981; Kobayashi, 1983). It can also be reasonably inferred from the archaeological context and ethnographic data that these tools were associated with scraping, slicing, and chopping actions, as well as piercing and sharpening. This site cluster, therefore, is discriminated by a toolkit characterized by a weighted combination of different kinds of fishing equipment and secondary tools for food resource processing and tool-making. Seasonal Round of Jomon Subsistence ActivitiesThus we find, in comparing regional differences in Jomon hunter-gatherer adaptations from an ecological viewpoint, that area-specific interassemblage variabilities are due to activity differences adapted to different environmental conditions. Western Jomon huntergatherers developed a procurement system which relied more on plant resources from a laurel forest ecosystem, and so prepared an appropriate tool-kit. Other Jomon groups, at least the two different groups of coastal hunter-gatherers from eastern Japan, developed more specialized fishing-hunting procurement systems, with less specialized plant collecting activities, and this was reflected in the tool-kit. In other words, terrestrial productivity, diversity, and biomass (particularly of edible plants), played a more critical role in the west and in the eastern interior, whereas the coastal subsistence procurement system in the east stressed the marine component, as developed in transitional zones between two major ecosystems: forest and estuarine/ Pacific shelf littoral. The objective of creating these models for Jomon territorial differentiation was to construct a set of generalizations about how Jomon site locations were structured ecologically. They show that Jomon sites were located in transitional areas between different ecological zones in order to ensure constant and reliable levels of food resources. The most significant criteria relevant to these locational decisions pertain to seasonal variation in resource abundance and availability. Edible-plant ProductivityUnder Japanese forest conditions, plant productivity provided the most stable primary food supply for the Jomon hunter-gatherers. This view, inferred especially from the ethno- archaeological approach to Japanese forest edible-plant productivities (e.g., Koyama, 1981; Matsuyama, 1981), has often been endorsed. All these studies emphasize the superior productivity of chestnut (Castanea crenata), walnut (Juglans mandshurica), hazelnut (Corylus sieboldiana), and acorn (Castanopsis cuspidata) in forest ecosystems, as opposed to maritime productivity. Nishida (1983) claims that there was exploitation of intensively tended plants such as chestnut and walnut during the Jomon period, and that storage of these seasonally abundant resources was one of the most important strategies for maintaining economic stability. Storage behavior is manifest at some Jomon habitation sites by the presence of underground pits containing various nuts and acorns (e.g., Makabe, 1979; Otomasu, 1984). However, the actual importance of plant resources in the Jomon hunting-gathering economy should be measured in terms of a seasonal productivity round covering all parts of the ecosystem within the exploitation territory. If Jomon hunter-gatherers exploited all the edible parts of about 300 available wild plant species, a year-round continuation of plant collecting activities could be practiced in the forest ecosystem, although some seasonal fluctuations in intensity would clearly be present (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, the most highly productive season had to be concentrated in autumn around October, when various fruits and seeds, the most important plant products nutritionally, were obtained (Table 2).

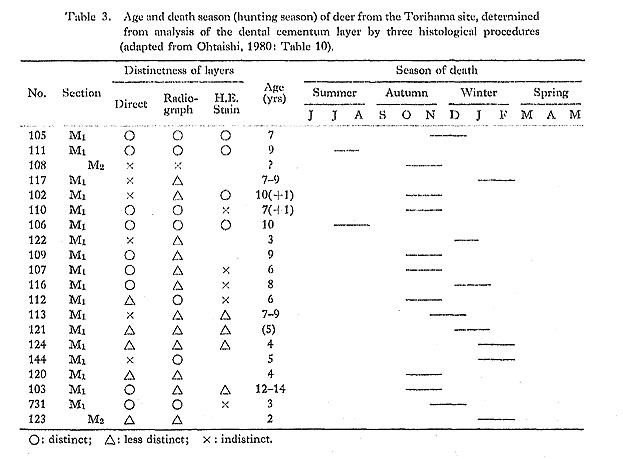

Other edible parts of plant resources were probably not a major food source, although they could be a resource to fill up the lean seasons. Land Animal ProductivityThe general conclusions of faunal analysis of Jomon midden deposits indicate a wide utilization of land animal resources in different ecological zones. The main concern of Jomon people was the hunting of larger game such as deer (Cervus sp.) and wild boai (Sus sp.). This view is supported by the evidence that these are dominant species in midden deposits of Jomon sites and their nutritional value per individual is much higher than the other species (e.g., K. Hayashi, 1971; Nishimoto, 1978). Examinations of the seasonality of these species fall into two types: techniques for estimating the date of death of an organism by counting seasonal growth lines, and techniques for estimating the most likely periods of hunting on the basis of animal behavior. Concerning the hunting seasonality of these species, the scanty available data are suggestive only rather than conclusive. Ohtaishi (1980) seasonally dated several random samples of deer from the Torihama site, an Early Jomon site in western Japan. The research method used was identification and interpretation of growth rings in the secondary dental cementum. The samples show a clear dominant season (Table 3): a marked mid-to-late autumn (October to December) peak followed by a decrease in mid-winter, reaching negligible or almost zero levels in spring, summer, and early autumn. These observations, should, however, be qualified by noting that they are based on data from one site only. Nevertheless, these results do not contradict a previous hypothesis that deer and wild boar hunting was greatest in winter, as inferred from the ethnographic data and ecological habits of these species (e.g., Nishida, 1980; Ohtaishi, 1983; Y. Hayashi, 1983).

Maritime ProductivityIn examining the seasonal round of maritime productivity among the coastal Jonion people of eastern Japan, we find that the most common fish from midden deposits are of species which migrate in estuarine zones, coming close to shore during their breeding and feeding activities in early spring and summer. Dominant species such as the red snapper (Chrysophrys major), black snapper (Acanthopagrus schlegeli), and sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus), found in midden deposits along eastern Pacific coastal regions, were probably caught during spring to summer (e.g., Akazawa, 1969, 1980, 1981, 1982b). Open ocean species such as those of the family Scombridae, very common in Jomon shell middens of the Tohoku district, were also caught when they migrated along the rocky-shore zones during the summer season (Akazawa, 1981). Obviously a number of criticisms can be made of results based upon indirect evidence, in particular such evidence as the ecological habits, breeding patterns, and related behavior of living species. Nevertheless, the majority of the dominant fish species from Jomon shell middens were very probably caught from spring to summer, during the season of least plant productivity (Akazawa, n.d.b.). With regard to the seasonality of shellfishing, Koike (e.g., 1973, 1979, 1980, 1985) states from extensive studies of dominant molluscan species such as clam (Meretrix lusoria), shortnecked clam (Tapes japonicus), and corbicula (Corbicula. japonica), from Jomon shell middens, that the greatest number of total shells dated from spring to summer. This percentage decreased gradually in later summer and autumn, reaching almost zero in winter. A number of marine faunal remains have been excluded from studies of this kind and it is unsafe to argue that the possibility of autumn and winter fishing (including shellfishing) activities should be ignored completely. For instance, Jomon salmon fishing had to be practiced in both summer and autumn, based upon the ecological habits of living species. But it is still a controversial topic (Matsui, 1985), since bone fragments of the species have only been found in negligible amounts in middens. The evidence presented to date, which represents the dominant species identified from Jomon sites, gives support for the possibility that these activities were carried out during a particular season, that is spring to summer, and not all year round. Seasonal Procurement Rounds of Jomon Hunter-GatherersSeasonal variation in the fulfillment of major subsistence needs-maritime exploitation from spring to summer, edible plant gathering in the forest especially in autumn, and large game hunting in winter-is a reflection of Jomon people's strategies for maintaining economic stability. Strategies for coping with seasonal fluctuations in resource abundance affected the seasonal range and intensity of resource exploitation, and thus the year was divided into several seasons corresponding approximately to the availability of major resources. Comparing procurement rounds of different Jomon groups based on seasonal fluctuations in productivities of major food resources, we find that forest-estuary and Pacific shelf littoral ecosystems could supply a much more stable seasonal procurement round than could forest-freshwater ecosystems. The procurement systems of eastern Jomon coastal groups were characterized by the year-round overlapping of two major productivities: maritime resources available from spring to summer, and edible plants from the forest, available especially in autumn; additionally, there was supplementary hunting on land in winter. That is, the eastern Jomon subsistence economy incorporated different major resource exploitation patterns for coping with seasonal fluctuations in resource abundance and availability. Jomon peoples in the west and in the eastern interior developed a procurement system which relied more on plant resources from the forest ecosystem. In other words, terrestrial productivity, diversity, and biomass (especially of edible plants), played a critical role in their exploitation patterns. ConclusionThe recognition of regional variation in procurement systems of Jomon hunter-gatherers can be useful in understanding two controversial subjects in Japanese prehistory: (a) regional differences in Jomon population density, and (b) regional differences in Jomon receptivity to rice. Jomon PopulationThe differing distribution and density of Jomon population between lightly peopled western Japan and more densely populated eastern Japan has often been explained as stemming from differences between the eastern and western forest zones in the amount and nature of available foods. Certainly, the Jomon people might be expected to exploit terrestrial plants with a high nutritional value as stressed by some archaeologists (K. Suzuki, 1979; Nishida, 1980, 1983); however, most potential resources could only be exploited seasonally. In particular, all of the vegetable resources identified in the Jomon deposits are seasonally specific. Population size and density are closely related to the environmental productivities exploited by hunter-gatherers (e.g., Clarke, 1976; Yesner, 1980; Perlman, 1980; Hassan, 1981). However, the crucially important fact is that productivities should be measured in terms of a seasonal productivity round and the procurement system associated with it. A higher population density in the coastal Jomon societies of eastern Japan can be explained by the existence there of a procurement system characterized by the year-round continuation of two or more major productivities, as developed in transitional zones between two major ecosystems: forest and estuarine/Pacific shelf littoral. By contrast, western Japan was less densely populated because the procurement system there was maintained by forest edible-plant productivity of various nuts and acorns highly concentrated only in autumn; western Japan lacked the overlapping functional combination of maritime and terrestrial productivities that operated in the eastern coastal regions. In other words, higher population density along eastern Pacific coastlines, rather than being a consequence of high edible-plant productivity, was a function of the manner in which terrestrial resources were incorporated into marine resource exploitation systems; conversely, population density in the west was directly supported by terrestrial plant use. Thus, the differing distribution and density of Jomon population between western and eastern Japan is explainable as resulting from variation in seasonal combinations of major productivities between the two areas. Jomon Receptivity to RiceThe western Jomon people gained a high degree of botanical experience in their terrestrial procurement system in laurel forest zones, and therefore evolved an appropriate cultural milieu that increased their receptivity to adopting a rice culture. These circumstances fostered a technology with high potential for agriculture, such as their tool-kit composed of harvesting and compound tools and storage facilities. Agriculture could be smoothly incorporated into their procurement system because the cultivation of rice did not conflict with the already established seasonal procurement round. One of the most regulated seasons in rice agriculture, that of planting and weeding, takes place in spring through summer, when forest productivity was low, as discussed above. The adoption of rice agriculture may also have been reinforced by western Japan's proximity to the continent and its biophysical similarities to the areas providing the stimulus to rice cultivation. Conversely, where the procurement system was more rigidly regulated by the seasonal scheduling demands of two or more major productivities, as in the case of the eastern coastal Jomon societies where maritime resources were well incorporated into terrestrial resource exploitation systems, then such agricultural innovation would have been resisted. Special attention should be paid to the fact that the rice planting and weeding season conflicted with the eastern coastal Jomon people's fishing and shellfishing season. Maritime resources constituted a major food supply for them and they had developed a specific tool-kit composed of a large variety of fishing equipment to facilitate their procurement. Further, we should consider such social factors as working arrangements within the local societies. In sum, the most crucial point in mediating the transition to rice agriculture in Japan was the extent of cultural readjustment that was needed. In western Japan, little readjustment was necessary; in eastern Japan, with its highly developed hunting-gathering efficiency, the adoption of food production initially threatened the socio-cultural system, and therefore agriculture was only gradually and differentially taken up. References

|