CHAPTER 2

Material and Method of Study

|

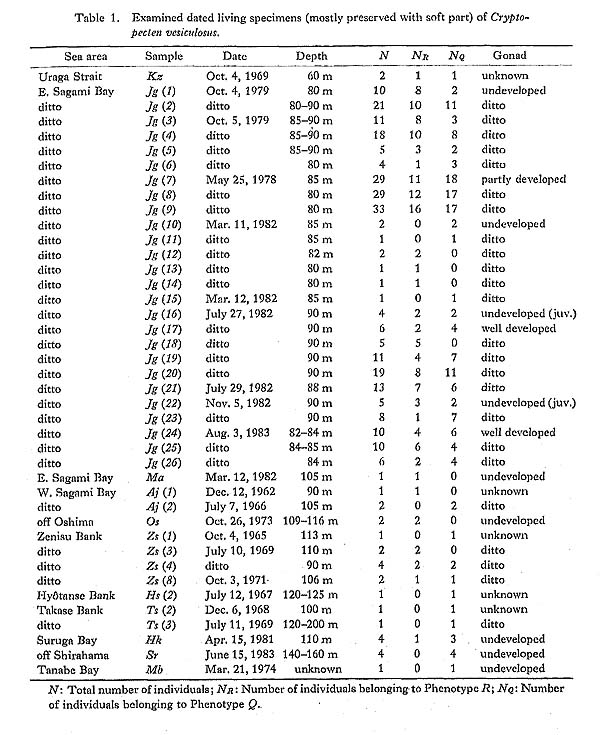

In order to detect geographic and chronological change of morphometric characters within an evolutionary lineage and to clarify morphological difference between lineages, many large random samples from various areas and horizons are indispensable. Although many fossil and Recent specimens of Cryptopecten are preserved for comparative studies in several museums, institutions and private collections in Japan, in many cases they are unsuitable for the present study because of meagre sample size, possibility of artificially biased sample preparation, or poorly documented locality and horizon. For the past ten years, therefore, I have endeavored to collect and observe as many sets as possible of large samples which faithfully represent local populations. With the cooperation of a large number of scientists and amateurs I was able to examine 40 fossil samples and 30 Recent samples (including 115 subsamples) of Cryptopecten vesiculosus, as documented in the annexed list (p. 122). The total number of individuals comes to about 20,000. These samples appear to cover the main geographic and stratigraphic distributions of this species. The 17 samples treated in my 1973 paper were studied again and reanalyzed, because the biometric method of study and standardization of characters employed in the present study differ slightly from those used in the earlier one. More than 270 living individuals of C. vesiculosus with soft parts were available for this study (Table 1), Most of them were obtained in six different seasons from sandy bottom near the edge of the continental shelf of eastern Sagami Bay. Though many individuals are immature (probably yearling), this sample, Jg (1-26), gives useful information about reproductive biology and population structure. The strictly sympatric relation of the two discrete phenotypes is also ascertained in this sample. This sampling locality was very convenient because of its proximity to the Misaki Marine Biological Laboratory of the University of Tokyo.

Another promising sea area for the investigation of living populations of C. vesiculosus is located near the mouth of Ise Bay, especially the sandy bottom about 10 km east of Cape Anori near Toba City. Though I have not yet succeeded in collecting living individuals, more than 300 fresh and conjoined valves (Sample Is) were collected from the wastes of a commercial fishery in this sea area by Mr. S. Hayashi. These are mostly mature and have proved very useful for the observation of general shell morphology (Plate 3, Fig. 5).

Several dated living specimens from Zenisu and two other sea banks west of Izushichitô Island (Samples Zs, Hs and Ts) provided by Dr. T. Okutani, and specimens from the southeastern part of Suruga Bay (Sample Hk) collected by Dr. H. Kitazato, are also important for the observation of shell growth because they were collected in several different seasons. The fossil samples of C. vesiculosus are considerably biased in time and space. About half of them are from the Upper Pliocene and Pleistocene on Boso Peninsula, where at least seven horizons can be discriminated. In other areas, however, occurrence of large fossil samples is rather sporadic. Great improvements in the correlation and chronology of the Neogene and Quaternary deposits in Japan have been made over the past ten years through studies of widely distributed tephras, various radioactive isotopes, fissiontrack dating and paleo-magnetism in addition to biostratigraphic zones and microfossil datum planes. Though there is much room for further improvement, the absolute ages of many fossil beds yielding Cryptopecten samples have become much clearer. The absolute ages adopted in the present paper are mainly based on those given by Tsuchi (1981 ed.) for the Neogene and Lower Pleistocene and by Machida et al. (1971, 1974) and Sugihara et al. (1978) for the Middle-Upper Pleistocene of Boso Peninsula. With these samples I attempt to restore the evolutionary pattern of C. vesiculosus. Restoration of phyletic evolution, I believe, should be achieved through three steps: examination of individual variation within each local population and its causal evaluation, recognition of geographic variation, the spatial integration, so to speak, of intrapopulational variation, and chronological integration of geographic variation. In the case of C. vesiculosus, although geographic variation in the geological past is still difficult to recognize, morphological difference outside the maximum range of geographic variation in Recent samples may be attributable to evolutionary change. As to other Indo-Pacific extant species of Cryptopecten, only a small number of new samples were obtainable. As shown in the annexed list of examined samples, some specimens of Cryptopecten bullatus and Cryptopecten nux from south Japan were available for this study, but they were generally too small in sample size to permit detection of any biometrically significant morphological change with time. Much less is known about the geographic distribution and evolutionary change of the two extinct species, Cryptopecten yanagawaensis from the Middle Miocene of central and north Japan and Cryptopecten spinosus sp. nov. from the Upper Pleistocene of south Japan, because they are now represented only by samples of a few and a single fossil population, respectively. Recently, I had the opportunity to examine the large collections of Recent pectinids in the National Museum of Natural History, Washington P. C. and the American Museum of Natural History, New York, through the courtesy of the curators of these museums. These collections include a large number of Recent samples of C. bullatus (commonly labelled C. alli) and C. nux (sometimes labelled C. bernardi or C. corymbiatus) from extensive areas of the Indo-Pacific as well as Cryptopecten phrygium from the western Atlantic. The samples collected by R/V Albatross of the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries in Southeast Asia, which are preserved in Washington, D. C., are well documented and were especially useful for this study. The geographic distribution and systematic description of these uncommon species are mainly based on my research on these collections. Nomenclatorial revision and synonymic assignment of some early described species of this genus was possible after my examination of Dr. T. R. Waller's unpublished data and photographs of the type specimens of these species in several European institutions. In the present study all the known species of Cryptopecten, both fossil and living, were studied in order to understand the evolutionary history of this genus. Understanding of their interspecific relation and the process of speciation are, of course, the central aim, although owing to incomplete fossil records the method of study is often confined to conventional comparative morphology. The following abbreviations are used for the indication of institutions where the specimens under discussion are preserved: BM (NH): Department of Zoology, British Museum (Natural History), London. USNM: Department of Invertebrate Zoology (Molluscan Division), National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D, C. AMNH: Department of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, N. Y. IGPS: Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Faculty of Science, Tohoku University, Sendai. UMUT: Department of Historical Geology and Palaeontology, University Museum, University of Tokyo, Tokyo. NSMT: Department of Zoology, National Science Museum, Tokyo. |