ALPINE VEGETATION AND ITS PATTERN ON JALJALE HIMAL, EASTERN NEPAL

|

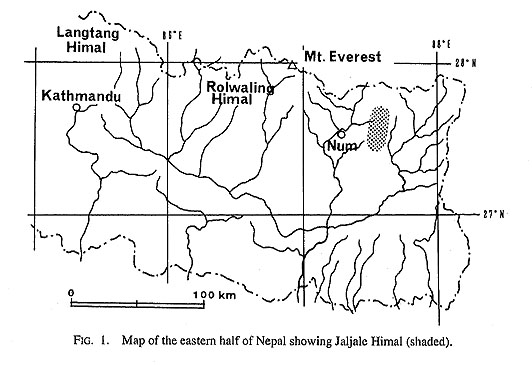

Eastern Nepal is under the direct influence of rain brought by the monsoon wind from the Bay of Bengal. Annual precipitation greatly exceeds 2000 mm, being as high as 4000 mm, as recorded in Num. In more southern, lower altitude regions the amount is less than 1000mm. There is also an apparent dry season which last six to eight months from autumn to spring (Shakya 1983). Vegetation is affected by these different aspects of climate. According to remains of natural forests on mountainsides in the area, luxuriant evergreen broad-leaved forests would covers the area if not for the activities of humans. This type of forest evolves in a climate with sufficient rainfall. I n contrast, vegetation is more or less affected by seasonal aridity, as shown by the seasonal forests of Shorea robusta at the foot of the mountains. The forest zones in eastern Nepal have been classified by Yoda (1967), Ohsawa et at. (1973) and Ohsawa (1977, 1983) as follows:

There is a scrub zone dominated by several species of Rhododendron, particularly Rhododendron campanulatum, above the Abies zone. The alpine zone in the present study is the region above the upper limit of this scrub zone from about 4000 m to the snow line, which usually lies at about 5000 m, although we could not investigate the upper half of the zone during this study. There were few actual stands of Abies forest along our trekking route even within the elevations of the Abies zone mentioned above. The forests in accessible places probably have been disturbed and replaced by other types of forests, such as the Rhodo dendron arboreum forest. This is most likely due to human impact, because Abies forests are still common on mountain-sides far from the route we followed. Vegetation is widely used for cattle grazing even in the alpine zone in the Himalaya. Human impact should be considered as one of an essential ecological factors in the establishment and sustenance of alpine vegetation. Daytime air temperature in summer are estimated at about 8° to 10°C at 4000 m and about 3° to 5°C at 5000 m above sea level based on Kikuchi and Ohba (1988a). According to the linear regression trend associated with an increase in altitude, soil temperature at a depth of 100 cm will be about 2°C at 4000 m and about 0°C at 4200 m above sea level in spring (Yoda 1989). Ground surface is mostly free from fluvial erosion except for narrow portions along gullies and streams. The upper half of the alpine zone is generally affected by periglacial frost action, but the effects are partial in the lower half. Thus, most of the area investigated in the present study is free from obvious instability due to fluvial erosion, frost action, and so on.

|

|

|

1. The Potentilla contigua community (Table 2)

|

The Potentilla contigua community is the commonest meadow community characterized by the occurrence of Potentilla contigua, Geranium nakaoanum and Cortia depressa and dominated by Potentilla contigua or sometimes Potentilla peduncularis. Perennial forbs, including Rheum acuminatum, Saussurea sughoo. Primula primulina and others, were prominent as well as the dominant and characteristic species. They were accompanied by perennial grasses, sedges and rushes such as Festuca polycolea, Kobresia nepalensis and Juncus leucanthus. The community was usually 15-30 cm tall, one occasionally as short as 10 cm and as tall as 50 cm, and covered 70% of the ground or more. The ground surface of the habitat was usually soil consisting of rock fragments and other fine materials.

Some species, such as Rhodiola discolor, were found in some of the stands classified as this type of community, and Gentiana sp. and Festuca polycolea at others. Some stands have none of these. Thus, this type of community was apt to vary from stand to stand in composition of species. It can be subdivided into several types.

2. The Bistorta vaccinifolia community (Table 3)

|

The Bistorta vaccinifolia community is a scrub dominated by deciduous, low shrubs of Bistorta vaccinifolia and/or Potentilla fruticosa var. rigida and characterized by the occurrence of a fern, Athyrium cuspidatum, and a perennial forb, Rhodiola himalensis, as well as the dominant shrubs. Other conspicuous species such as the forbs Potentilla peduncularis, Rheum acuminatum, Koenigia delicatula, Saussurea sughoo, Bistorta jaljalensis, the sedge Kobresia nepalensis, the rush Juncus leucanthus, and so on, were common in the Potentilla contigua community. The community was usually 40 cm tall and occasionally as short as 10 cm, and covered 60-80% of the ground. It was found on rocky sites such as scree and the bottom of a gully on a talus where the matrix had been washed away and the boulders were exposed.

3. The Primula stuartii community (Table 4)

|

The Primula stuartii community is a meadow dominated by perennial forbs of Primula stuartii and Potentilla peduncularis. Forbs of Lagotis cunaurensis, Primula stuartii and Primula sikkimensis, and a rush of Juncus sp. were specific to this type of community. Other components, such as Kobresia nepalensis, Juncus leucanthus, Koenigia delicatula, Saussurea sughoo, Bistorta jaljalensis, and so on, were common to the former two types of communities. The height of the community was 30-50 cm, but occasionally was as low as 15 cm and as tall as 60 cm. It covered 60-90% of the ground, which consisted of rock fragments and finer materials. The habitat was wet or waterlogged.

4. The Rhododendron anthopogon community (Table 5)

The Rhododendron anthopogon community is one of the commonest communities of evergreen dwarf scrub dominated by Rhododendron anthopogon and characterized by the occurrence of Bergenia purpurascens and Salix anticecrenata. Cremanthodium pinnatifidum and Swertia multicaulis were common to the following four communities, although they were infrequent. There were no other conspicuous species common to the other communities except for Kobresia nepalensis. The community was 20-40 cm tall and covered 70-95% of the ground. The habitat has a comparatively thick surface deposit of rock fragments and other fine matter.

5. The Rhododendron anthopogon-Potentilla microphylla community (Table 6)

The Rhododendron anthopogon-Potentilla microphylla community is also an evergreen dwarf scrub dominated by Rhododendron anthopogon but distinguished from the Rhododendron anthopogon community by the absence of Bergenia purpurascens and Salix anticecrenata and the association with Cremanthodium pinnatifidum, Potentilla microphylla and Swertia multicaulis, which were common to the communities mentioned below. On the other hand, it has no characteristic species of its own. It could be an intermediate community between the Rhododendron anthopogon community and those mentioned below. The community was very low, ranging from 5 cm to 10-20 cm tall, and covered 70-90% of the ground.

6. The Kobresia nepalensis community (Table 7)

|

The Kobresia nepalensis community is a meadow characterized by a sedge of unknown Kobresia and forbs of Potentilla coriandrifolia, Aletris pauciflora, Gentiana sp. and low shrubs of Rhododendron setosum. It included many forbs such as Cremanthodium pinnatifidum, Potentilla microphylla, Swertia multicaulis as well as those mentioned above, but sedges of Kobresia nepalensis and another unknown Kobresia were more prominent than forbs. It was 10-20 cm tall and covered 70-90% of the ground. The community was specifically found on basement rock with very thin surface sediment.

7. The Rhodiola coccinea community (Table 8)

The Rhodiola coccinea community is a community found on scree and stream bed. It is dominated by Rhodiola coccinea, which is specific to this community, and includes Poa eleanorae and Corydalis sp. Small forbs of Parnassia pusilla, Arenaria sp., Sibbaldia sp., Paraoxigraphis sp., Koenigia delicatula, and so on, were frequent. Sedges and rushes were not common. The community was 5-15 cm tall and covered 10-30% of the ground.

8. The Kobresia duthiei community (Table 9)

The Kobresia duthiei community is an alpine desert consisting of Parnassia pusilla, Arenaria sp., Sibbaldia sp. and Paroxygraphis sp., which are common to the Rhodiola coccinea community, and Kobresia duthiei, Cremanthodium pinnatifidum, Potentilla microphylla and Swertia multicaulis, Kobresia nepalensis, Juncus leucanthus, Koenigia delicatula, and so on, widely found in other communities. Thus, this community was closely related to the Rhodiola coccinea community in floristic composition but Rhodiola coccinaea, Poa eleanorae and Corydalis sp. were lacking and sedges and rushes were comparatively conspicuous. Vegetation height was as low as 3-10 cm and vegetation cover was usually 5-10%, although occasionally it was 40%.

Kikuchi and Ohba (1988) studied alpine plant communities on Rolwaling Himal in the easternmost part of central Nepal, and Miehe (1990) studied communities on Langtang Himal in central Nepal, which partly included alpine steppes of South Tibet. Miehe proposed three classes of plant communities based on his phytosociological research: Kobresietea nepalesis prov. (Himalayan-alpine Rhododendron-Kobresia mats), Caricetea montis-everestii prov. (alpine steppes of South Tibet) and Potentilletea eriocarpae (rock wall communities). Furthermore, he classified a number of subordinate vegetation units with their characteristic and/or differential species. All of the eight plant communities described in the present study should be included in his Kobresietea nepalensis prov. and briefly compared to his larger subordinate units of the class along with those described in Rolwaling Himal by Kikuchi and Ohba (1988b).

Distribution Patterns in Relation to Some Habitat Characteristics

As already described, the Bistorta vaccinifolia community was found on rocky sites such as scree and gulley bottoms, the Rhodiola coccinea community was on the surface of scree rocks and in stream beds, and the Kobresia duthiei community was on desert-like sites affected by periglacial frost action. These habitats are unique to edaphic conditions mostly found on discontinuous, restricted portions but free from site properties such as exposure (Tables 3, 8 and 9). The other five types of communities more or less extended continuously. Among them, the Potentilla contigua community, the Rhododendron anthopogon community and the Primula stuartii community were supported on slopes where soils were to some extent developed based on surface deposits of rock fragments and fine matrix. Slope properties of the habitats of these communities are shown against their slope exposure and slope inclination at the top in Fig 2. Slopes facing east-south-west support the Potentilla contigua community, those facing west-north-east the Rhododendron anthopogon community and both of them the Primula stuartii community when they were gentle or level. The Rhododendron anthopogon Potentilla microphylla community and the Kobresia nepalensis community, which inhabited exposed basement rock with very thin surface deposits, were found on slopes facing west-north-east and slopes mostly facing east-south-west, respectively, as shown at the bottom in Fig. 2. However, the Kobresia nepalensis community also inhabited slopes facing north and their vicinity when they were gentle. The habitat facing north is usually characterized by shade from solar radiation, but even such slopes are exposed to sunshine if they are gentle. Such slope conditions would not be suitable for the Rhododendron anthopogon-Potentilla microphylla community nor for the Rhododendron anthopogon community.

Kikuchi and Ohba (1988b) determined that the existence of the plant communities in the alpine zone of Rolwaling Himal around the border between central and eastern Nepal were affected by four kinds of conditions in relation to small-scale or micro-scale geomorphic properties of their habitats. They are: thermal condition or altitude, sunlight due to slope exposure, frost action caused of slope exposure through wind, and edaphic conditions. Altitude and wind effects were not apparent in the present study because altitudinal differences among the sample plots were not large enough and the altitudes of the plots were not high enough for the occurrence of periglacial frost action. On the other hand, the effects of slope inclination were obvious as were those of sunlight due to slope exposure and edaphic conditions. Miehe (1989) showed the same-scale distribution pattern of vegetation in the alpine zone of Mt. Everest, particularly vegetation differences between "shady slopes protected from the wind" and "sunny slopes exposed to the wind." He emphasized wind as the limiting factor for the rhododendrons in the alpine zone in association with temperatures below 0°C and the absence of snow protection. However, differences in solar radiation itself in relation to both slope exposure and inclination should be considered also.

Conclusions

The following eight plant communities were recognized based mainly on their species composition: 1) the Potentilla contigua community, 2) the Bistorta vaccinifolia community, 3) the Primula stuartii community, 4) the Rhododendron anthopogon community, 5) the Rhododendron anthopogon-Potentilla microphylla community, 6) the Kobresia nepalensis community, 7) the Rhodiola coccinea community and 8) the Kobresia duthiei community. They were arranged according to the differences associated with three kinds of habitat conditions: 1) slope exposure in relation to solar radiation, 2) slope inclination in relation to soil water and solar radiation and 3) edaphic conditions.

References

- Braun-Blanquet, J. 1964.

- Pflanzensoziologie. 865pp. Springer-Veriag, Wien, New York.

- Kikuchi, T. & H. Ohba. 1988a.

- Daytime air temperature and its lapse rate in the monsoon season in a Himalayan high mountain region. H. Ohba & S. B. Malla (eds.), The Himalayan Plants, vol. 1, 11-18.

- Kikuchi, T. & H. Ohba. 1988b.

- Preliminary study of alpine vegetation of the Himalayas, with special reference to the small-scale distribution patterns of plant communities. H. Ohba & S. B. Malla (eds.), Himalayan Plants, vol. 1: 47-70. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo.

- Miehe, G. 1989.

- Vegetation patterns on Mount Everest as influenced by monsoon and föhn. Vegetatio, 79: 21-32.

- Miehe, G. 1990.

- Langtang Himal, Flora und Vegetation als Klimazeiger und -zeugen im Himalaya, a prodromus of the vegetation ecology of the Himalayas. 494 pp. J. Cramer, Berlin, Stuttgart.

- Ohsawa, M. 1977.

- Altitudinal zonation of vegetation in eastern Nepal Himalaya. Pedologist, 21:76-94.

- Ohsawa, M. 1983.

- Distribution, structure and regeneration of forest communities in eastern Nepal. M. Numata (ed.). Structure and Dynamics of Vegetation in Eastern Nepal, 89-120. Chiba University.

- Ohsawa, M., P.R. Shakya & M. Numata. 1973.

- On the occurrence of deciduous broad-leaved forests in the cool-temperate zone of the humid Himalayas in eastern Nepal. Jap. J. Ecol. 23:218-228.

- Shakya, P. R. 1983.

- Vegetation study in east Nepal. M. Numata (ed.). Ecological Studies in the Tamur River Basin, East Nepal, and Mountaineering of Mt. Makalu II, 1977, 123-138. Chiba University.

- Yoda, K. 1967.

- A preliminary survey of the forest vegetation of eastern Nepal. J. Coll. Arts and Sci., Chiba Univ., 5: 99-140.