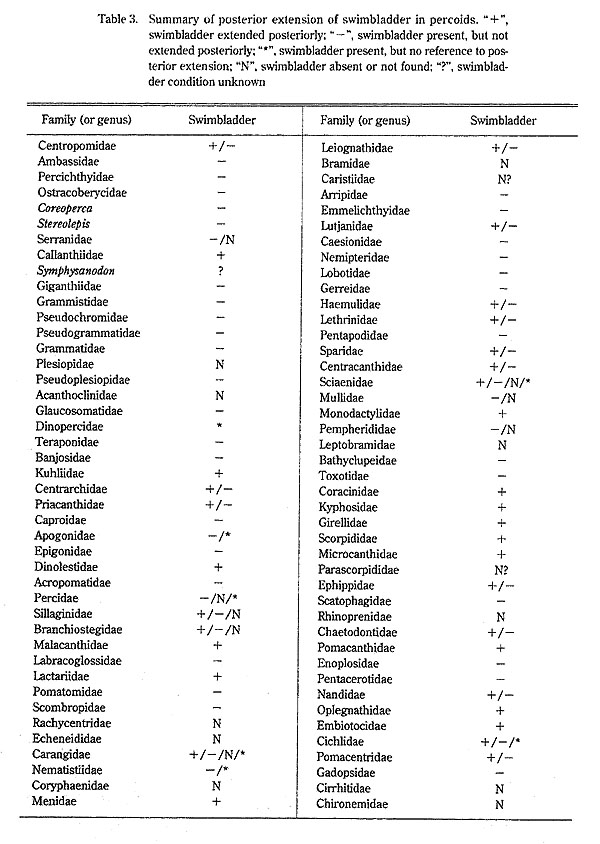

The distribution of a posterior extension of the swimbladder in percoids is given in Table 3, being compiled from specimens examined during this study and literature sources.

Judging from the development and phytogeny of the swimbladder in fishes (e.g., Jollie, 1973; Cambray, 1990), a posterior extension should be considered an apomorphy for percoids, with the absence of a swimbladder also being considered apomorphic, as Harder (1975:166) stated "In case the swimbladder is missing in some Osteichthyes this is always a secondary development."

On the basis of the presence or absence of the swimbladder and a posterior extension, per-coid fishes examined in this study and elsewhere are classified into six groups.

(1) Posterior extension present (+ in Table 3): Callanthiidae, Kuhliidae, Dinolestidae, Malacanthidae, Lactariidae, Menidae, Monodactylidae, Coracinidae, Kyphosidae, Girellidae, Scorpididae, Microcanthidae, Pomacanthidae, Oplegnathidae, and Embiotocidae.

In these families, it is probable that the posterior extension is not a synapomorphy for the whole group, because of the variations in the characteristics of the extensions, such as the degree of extension and association with caudal ribs. The derived state seems to have occurred independently in individual families or some limited family groups.

There is, however, no doubt that a posterior extension is a synapomorphy of the following families: Dinolestidae, Malacanthidae, Lactariidae, Menidae, Monodactylidae, Pomacanthidae and Embiotocidae. The extension in each family is characterized by its own unique structure, such as the degree of extension, modification of haemal spines, and their associated anal-fin proximal pterygiophores and caudal ribs (see Results and Comments).

The modifications of the haemal spines seen in Malacanthus (Malacanthidae) and Pseudo-cepola (Owstoniidae) are probably not homologous, because of differences in several other aspects, such as the degree of extension, strength of the membrane and the presence or absence of associated caudal ribs.

In the Embiotocidae, this study suggests that Brachyistius, Ditrema, Embiotoca,Hysterocarpus, Micrometrus, Neoditrema and Phanerodon constitute a monophyletic group, owing to the posterior extension in these genera being partially perforated by haemal spines. However, more detailed studies are needed for a final conclusion.

With regard to the remaining families, including the Callanthiidae, Kuhliidae, Coracinidae, Kyphosidae, Girellidae, Scorpididae, Microcanthidae and Oplegnathidae, whether or not the presence of a posterior extension has been independently derived by each family, or repre-sents a synapomorphy of some limited family groups or, in fact, whole group, cannot be deter-mined without further, more detailed studies.

(2) Posterior extension present or absent (+/-)): Centropomidae, Centrarchidae, Priacan-thidae, Leiognathidae, Lutjanidae, Haemulidae, Lethrinidae, Sparidae, Centracanthidae, Ephippidae, Chaetodontidae, Nandidae, Cichlidae, Pomacentridae, Owstoniidae, and Cepolidae.

The presence or absence of a posterior extension has been used in taxonomic and/or phylogenetic studies of the Centropomidae by Greenwood (1976), Priacanthidae by Starnes (1988) and Cichlidae by Kullander (1986).

Amongst the Lutjanus species (Lutjanidae) examined here, it is probable that L. ophuysenii and L. vitta constitute a sister group because of their common possession of a unique posterior extension (see Results and Comments).

Pseudocepola taeniosoma (Owstoniidae), like species of Acanthocepola (Cepolidae), clearly shows a derived feature in terms of the possession of unique structures in the swimbladder extension (see Results and Comments).

(3) Posterior extension present or absent, or swimbladder absent (+/-/N): Sillaginidae and Carangidae.

McKay (1988) considered swimbladder morphology to be important in the classification of the Sillaginidae.

Based on the Carangidae examined here, it appeared possible that both the presence of a posterior extension and the absence of a swimbladder will be useful in phylogenetic studies. It is suggested that Decapterus, Selar and Trachurns form a sister group because of their common possession of a unique feature, the perforation of the extension by haemal spines. In Atropus atropus, Naucrates ductor and Parastromateus niger, whether or not the loss of the swimbladder has occurred independently or otherwise, cannot be discussed without detailed anatomical studies.

(4) Swimbladder present, posterior extension absent (-): Ambassidae, Percichthyidae, Ostracoberycidae, Coreoperca, Stereolepis, Giganthiidae, Grammistidae, Pseudochromidae, Pseudogrammatidae, Grammatidae, Pseudoplesiopidae, Glaucosomatidae, Teraponidae, Ban-josidae, Caproidae, Epigonidae, Acropomatidae, Labracoglossidae, Pomatomidae, Scombropidae, Arripidae, Emmelichthyidae, Caesionidae, Nemipteridae, Lobotidae, Gerreidae, Pentapodidae, Bathyclupeidae, Toxotidae, Scatophagidae, Enoplosidae, Pentacerotidae, Gadopsidae, Cheilodactylidae, and Latrididae.

Although a posterior extension is absent in the above families and genera, the morphology of the posterior portion of the swimbladder would be useful in phylogenetic studies of the following groups.

It is probable that two species of Gerres (Gerreidae) examined here constitute a monophyletic group because of their sharing a unique structure in the posterior portion of the swimbladder (see Results and Comments).

In Lateolabrax, Malakichthys elegans (Percichthyidae), Acropoma (Acropomatidae), Eucinostomus (Gerreidae), and Calamus (Sparidae), the swimbladder is unique in that its posterior end extends into the hollow space of the first anal-fin proximal pterygiophore. Although it is unknown whether or not such a structure is homologous in these groups (homoplasious), it is highly probable that it has occurred independently in each, excepting the two percichthyids. Further investigations, including ontogenetic studies, are in order.

Within the Grammistidae, the possession of caudal ribs may be an important consideration in phylogenetic studies, although such were found only in Diploprion bifasciatum.

(5) Posterior extension absent or swimbladder absent (-/N): Serranidae, Percidae, Mullidae, and Pempherididae.

Regarding the Mullidae, this study indicated that the presence or absence of a swimbladder is a useful taxonomic and/or phylogenetic character, as in the Serranidae (Katayama, 1959). Percidae (Collette et al., 1977) and Pempherididae (Tominaga, 1968).

(6) Swimbladder absent (N) :Plesiopidae, Acanthoclinidae, Rachycentridae, Echeneididae, Coryphaenidae, Bramidae, Caristiidae (?), Leptobramidae, Parascorpididae (?), Rhinoprenidae, Cirrhitidae, Chironemidae, and Aplodactylidae.

Whether or not the loss of the swimbladder has occurred independently in each family or some limited family groups, is unknown.

The present study showed that a posterior extension of the swimbladder was an important character for taxonomic and/or phylogenetic studies of several groups of percoids. Apart from groups with unique structures, however, such as the families Dinolestidae, Lactariidae and Embiotocidae, and some genera, including Pseudocepola (Owstoniidae) and Acanthocepola (Cepolidae), it is difficult to determine whether or not the posterior extensions seen in more than one group are homologous.