DESCRIPTION OF THE SKULLS

Skull of Minatogawa I (Pl. 2. 1)

The skull of Minatogawa I is whitish brown in color, with dark spots, and is markedly mineralized. The skull is nearly complete. Its vault is almost entirely preserved except for the tips of the zygomatic processes of both frontal bones, the upper halves of both squamae of the temporal bones and the posterior margin of the foramen magnum of the occipital bone.

The maxillae are mostly preserved except for the bodies on both sides. The left zygomatic arch is broken off. The mandible is almost complete except for the gonial angle and coronoid process of the left ramus.

The best-preserved Minatogawa I skull is fairly large in size, with big brow-ridges and a slightly receding forehead. The glabella region is strongly developed. Neither the frontal nor parietal eminences are marked. The mastoid portions are massive with large mastoid processes.

The three main sutures of the skull vault are mostly not closed exocranially but entirely open endocranially. The condition of the suture closure seems to correspond to that of a modern man about 25-30 years of age (Todd and Lyon, 1924, 1925).

The occlusal surface of the dentition is so heavily eroded that all the teeth are worn down to the root necks. Nevertheless, the upper and lower molars (M1, M2) are affected by relatively slight attrition (2nd-degree attrition).

On the whole, the skull may be considered to belong to an adult male individual.

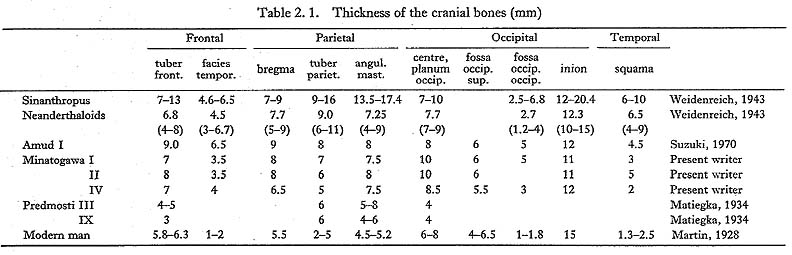

The thickness of the cranial vault (Table 2. 1)

The cranial vaults of the three skulls of the Minatogawa man are thicker than those of modern man and Predmost man in both sexes, but remarkably thinner than that of Sinanthropus. Minatogawa man is considered to fall within the variation range of the Neanderthaloids and to be almost the same thickness as the Amud man, which is considered to be the transitional stage between Homo sapiens and Neanderthaloid. Thus, the skull vaults of the Minatogawa man appears fairly thicker than those of modern man.

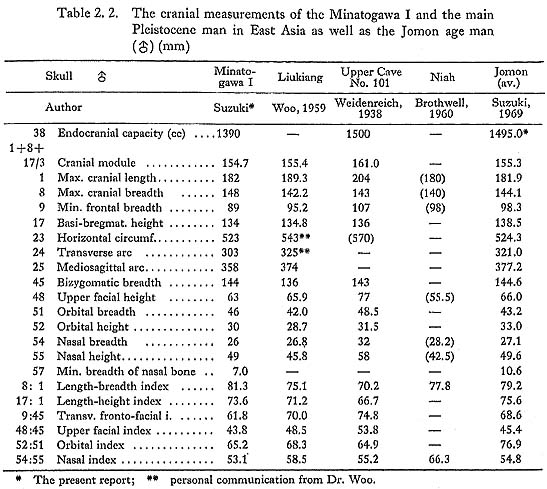

General aspect of Minatogawa I skull (Table 2. 2)

The skull as a whole is moderate in size for the male.

The maximum length of the skull (182 mm) is medium. Its maximum breadth (148 mm) is broad, and its cranial index (81.3) is brachycranic. The basi-bregmatic height (134 mm) and the auricular height (114 mm) are somewhat low.

The cranial capacity as estimated by the millet seed method is 1390 cc. The cranial capacity of the modern male Japanese is 1551.8 cc, on average, ranging from 1250 cc to 1920 cc. The average cranial capacity of the Jomon age male was 1495 cc, ranging from 1340 cc to 1660 cc. The cranial capacity of Minatogawa I, therefore, corresponds for the most part to a small cranial capacity range in the male prehistoric population in Japan.

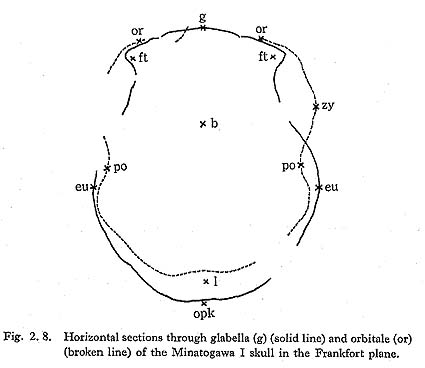

Norma verticalis of the Minatogawa I skull (Pl. 2. 1, d; Fig. 2. 8)

The Minatogawa skull I is ovoid in norma verticalis. The parietal tuberosities are medium prominent, and the maximum breadth of the skull lies at the tips of the two tuberosities. The position of the skull is expressed as the percentage of the maximum length, being 57.7%; the corresponding figure is 54.8% in modern man.

The most striking features of the Minatogawa I in norma verticalis are the forward swelling of the glabellar region, the lateral projection of the zygomatic process of the frontal bone and the strong protrusion of the zygomatic arches.

Viewed from above, the skull narrows anteriorly and then turns abruptly lateralward toward the zygomatic process of the frontal bone, which is much more robust and stouter than that of modern man.

The strongly developed glabella and superciliary arc are fused into a highly projected supraorbital ridge which has a rhomboidal form.

The coronal, sagittal and lambdoid sutures are not closed on either the external or internal tables, and the dentations look simpler than those in modern man. No partietal foramen is observed in the vicinity of the obelion region of the sagittal suture. The temporal lines on both parietal bones can clearly be seen from the vertical aspect, and they are shifted further upward than those in modern Japanese.

The minimum arc length between the two lines measured along the skull vault is 100 mm. Therefore, the ratio of this arc length to the transverse arc length of the skull (300 mm) is 33.3.

The contour behind the level of the maximum breadth of the skull is semicircular. The occipital part is round and blunt.

Norma later alis (Pl. 2. 1, b and c; Fig. 2. 7)

The lateral view shows an extremely prominent glabellar region at the front. The forehead is strongly inclined backward and is flattened. The inclination angle (g-b ∠ g-i) of 62° is nearly the same as the average value in the modern male Japanese, which is 59.9°.

The curvature angle of the frontal bone is 140°, which is larger than that of the modern male Japanese (130.7°).

The parietal bone is curved moderately, whereas the contour of the occipital bone is round and blunt.

The markedly developed linea temporalis shifts further upward than that in modern man. Near the lower end of this line, the bordering area between the supramastoid crest and the supramastoid sulus bulges to a toruslike round elevation of 13 mm in diameter, and is clearly separated from the salient supramastoid crest by a shallow sulcus. This elevation is most likely to coincide with the tuberculum supramastoideum anterius.

The markedly developed supramastoid crest extends forward up from the ear opening to the zygomatic crest. The zygomatic crest forms a widely overhanging roof above the external acusticus porus, and bears some resemblance to that of Sinanthropus.

The upper surface of the triangular shape of the root of the zygomatic arc, which was named sulcus processus zygomatici by Weidenreich, represents a groove widening anteriorly, which is broader than that normally in modern man. This form of the sulcus seems to have a close relationship to those of the temporal fossa and the zygomatic arc. The temporal fossa has the shape of an equilateral triangle when viewed from above. It looks much deeper and more spacious than that in modern man. The zygomatic arc spans the temporal fossa for a considerable distance from the cranial wall. The form of the zygomatic arc is different from that usually seen in modern man. The arc runs from the root of the zygomatic process of the temporal bone anterosuperiorly and then turns slightly downward to the temporal process of the zygomatic bone. The form of the zygomatic arc generally shows a wavelike form or a saber-hilt form (Plate 2. 1, c). This form of the zygomatic arc is also seen in primates and in some races of modern man such as the Wedda, Senoi and Ainu, and is regarded as one of the primitive features of the skull.

The lateralward bulging of the mastoid process is accentuated by the development of the mastoid crest, which continues posteriorly with the lateral prolongation of the occipital torus and combines anteriorly with that of the supramastoid crest. The supramastoid sulcus is well pronounced and relatively deep in the Minatogawa skull. The digastric fossa is not narrow like a cut, as is usually the case in modern man, but a wide and shallow groove, a trait held in common with Sinanthropus.

The external auditory aperture is obliquely inclined and elliptic, with a diameter of 11m. The meatal spine is moderately developed.

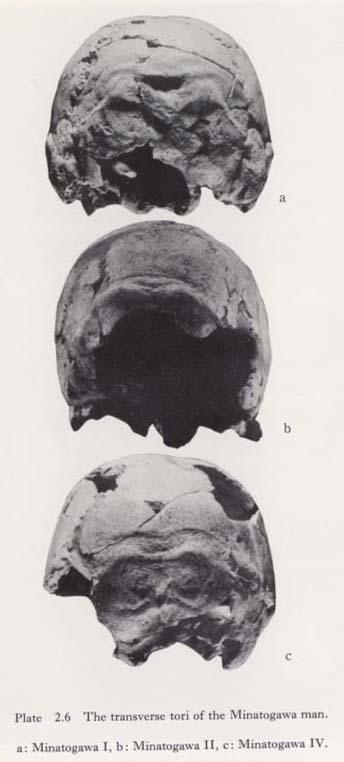

Norma occipitalis (Pl. 2. 1, d and Pl. 2. 6, a)

The occipital aspect of the Minatogawa I skull is almost circular. The well-developed tuberculum supromastoideum anterius and the massive mastoid process, which serve to make the lower part of the skull curve slightly inward, can be seen.

The muscle reliefs of the occipital bones are well developed. On the border between the occipital and nuchal planes, we can see the occipital torus. The tori consist of two oval tuberosities and a connecting portion between them (Pl. 2. 6, a).

The external occipital tuberosity is not seen; instead there is a deep counter-triangular depression just above the connecting portion. This depression is considered to be comparable to the suprainial fossae of Neanderthal man (McCown and Keith, 1939).

The tuberosities extend lateralward, forming sharp ridges, and connect to the crista mastoidea of the mastoid process, as has been stated already.

Norma frontalis (Pl. 2. 1, a)

The most characteristic features of the Minatogawa skull I from the frontal aspect are the round contour of the skull vault with its narrow forehead, well-developed supraorbital ridge, flat and broad face, low orbit, remarkably receded nasal root and wide nose.

The glabella and supercilliary arc are fused into a pronounced supraorbital ridge, rhomboidal in form, which stretches upward as the sagittal crest to the bregma. The zygomatic process of the frontal bone elongates almost horizontally lateralward to connect with the frontal process of the zygomatic bone. This is the reason for the enormously broad upper face in relation to the narrow forehead.

The minimum frontal breadth is 89 mm and the upper facial breadth is ca. 112 mm. The ratio of the former to the latter is 79.5. This figure is significantly less than that for Jomon age people (89.8) and for modern Japanese (89.8).

The form of the face of the Minatogawa skull I is broad and low. The bizygomatic breadth (144 mm) is broad, but both the facial height (107 mm) and the upper facial height (63 mm) are low. The facial index and the upper facial index are, thus, 74.3 and 43.8. Both index values indicate extremely low face types.

Of these values for the Minatogawa I skull, that for the zygomatic breadth is greater than the average value in modern Japanese (132.9 mm) and the same as that in the Jomon age population (144.3 mm). However, the facial height values are less than the average value for modern Japanese (115.0 mm, 67.1 mm) and that for the Jomon age population (115.0 mm, 66.0 mm). Therefore, the facial and the superior facial index of the Minatogawa skull I is much lower than either that of modern Japanese (93.1) or that of the Jomon age population (79.9). Thus, the Minatogawa I skull has a much lower face than the modern Japanese and the Jomon population.

Two sets of facial flatness measurements defined by Woo and Morant (1934) and naso-malar angles (facial measurements No. 77 after Martin, 1928) were taken on the Minatogawa I skull. The internal bi-orbital breadth (IOW) is 106 mm, the subtense of the nasion from the chord IOW is 11 mm and the frontal index of facial flatness is 10.4 cm, and the naso-malar angle is 156°. Compared with recent Japanese skulls, Ainu skulls and prehistoric Jomon skulls, the Minatogawa I skull is characterized by a much broader chord with lower subtense in the frontal regions and a broader chord with higher subtense in the zygomaxillary region, and by a larger naso-malar angle. These features result in a flatter upper face and a more protruding zygomaxillary region in the Minatogawa I than the average of those of the former three skull groups and even those of the Mongoloid skulls so far known (Yamaguchi, 1973, 1980). This suggests that the Minatogawa man belongs to one of the Mongoloid races.

The forward swelling of the supraorbital ridge is so remarkable that it overhangs the naso-frontal suture, giving rise to the remarkably receded nasal root of the Minatogawa I skull.

Of the bones of the nasal root, the nasal bones preserved about one-third their total length. The frontal process of the maxilla is quite intact on both side.

The minimum width of the nasal bone is 7.0 mm. This value is significantly smaller than the average value for the Jomon population (10.6 mm) and very much the same as that in the modern Japanese (7.0 mm). The lower breadth of the nasal bone is estimated to be 20 mm, according to the distance between the intact lower ends of the nasomaxillary surfaces on the frontal process of the maxilla. The transverse nasal bone index is thus 35.0, which is less than the average value in the modern Japanese (39.0).

The nasal bone on either side meets on the median line at right angles to give the general impression of a pinched nose.

The elevation of the nasal root, represented by the ratio of the chord length between the maxillo-frontal points (19.0 mm) to the corresponding arc length (24.0 mm) is 79.2. This value is intermediate between that for the Jomon age population (74.1) and that for the modern Japanese (84.4). Thus, the nasal root in the Minatogawa I skull is considered to be moderately elevated (Suzuki, 1969).

The nose of the Minatogawa I skull is low and wide. The nasal height is 49 mm, with a breadth of 26 mm and a nasal index of 53.1. It thus belongs to the chamaerrhine type. The nose of the Minatogawa man is lower in height and narrower in breadth than in the average modern Japanese (52.0 mm and 25.0 mm) and almost the same as the average in the Jomon age population (49.7 mm and 27.0 mm).

The lower margin of the apertura piriformis is not sharp but guttered. The lateral margin of the aperture unites with the anterior nasal spine. Between the anterior and posterior ridges, the latter of which runs from the anterior nasal spine to the wall of the aperture, a shallow but clearly circumscribed furrow can be seen. This furrow is the praenasal fossa, frequently seen in the South Sea population.

The orbits are wide and low. The superior orbital margin is straight and horizontal. The orbital breadth from the maxillo-frontal point is 46 mm on the left side and 45 mm on the right.

The orbital height is 30 mm on either side. The orbital index is thus 65.2 on the left and 66.7 on the right, in the higher range of chamaeconch types. Comparing the orbital form of the Minatogawa I skull with that of modern and prehistoric man in Japan, the Minatogawa's orbit is much wider, but much lower. The orbital type is thus in a much higher range of chamaeconch than that in the latter two populations.

Although large parts of the maxillae are broken off, the canine fossae are considered to be markedly developed.

The maxillo-alveolar length and breadth are estimated to be about 52 mm and 70 mm; the maxillo-alveolar index is 134.6. This index value means that the maxilla of the Minatogawa I skull belongs to the brachuranic type of maxilla. In relation to prehistoric Japanese, the Minatogawa maxilla is broader than that in the Jomon age population.

The malar bone as a whole is medium in size. The maximum height of the malar bone measured vertically to the masseteric border is 46 mm on the right side. The breadth, measured from the orbital end of the zygomatic-maxillary suture to the superior end of the zygomatico-temporal suture, is 44 mm on the same side. Since individual variation in modern male Japanese is 42-51 mm for height and 40-43 mm for breadth (Hasebe, 1925), these dimensions for the Minatogawa I skull correspond to the middle range of values in modern Japanese.

It should be noted that the malar bone is rotated more medialward than that in modern Japanese. This medial rotation of the malar bone seems to enhance the flatness of the Minatogawa I skull, as stated above. The malar tuberosity in the center of the malar bone is only slightly developed. In accordance with the lowness of the orbita, the frontal process of the malar bone is short but stout. A well-developed marginal tuberosity is seen on the posterior margin of the process.

The lower margin of the malar bone, which indicates a rough plane of attachment for the masseteric muscle, shifts at its anterior end directly to the lateral margin of the maxilla without a marked malar tuberosity. Therefore, the lateral margin of the maxilla does not show a sharply curved arch like that usually seen in modern man, but only a blunt concave arch. A remnant of the zygomatico-temporal suture runs horizontally from the posterior margin of the zygomatic process about 5 mm to the body of the malar bone.

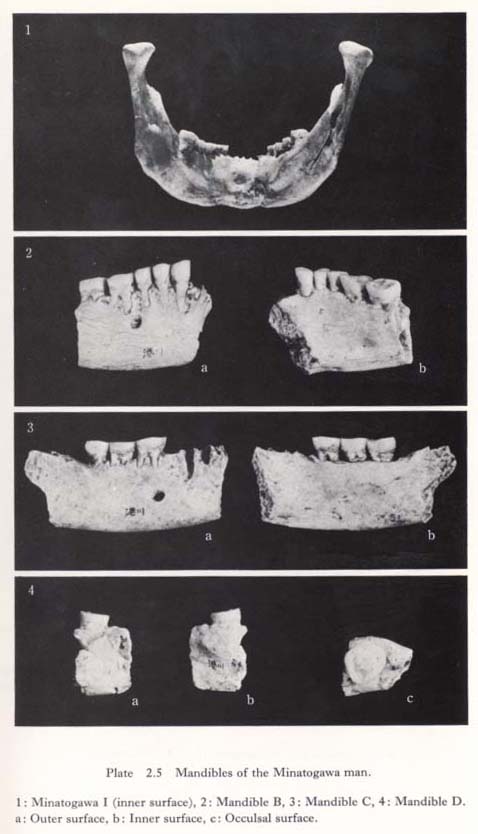

The lower jaw (Pl. 2. 1 and Pl. 2. 5, 1)

The lower jaw of the Minatogawa I as a whole is moderate in size but very robust. Since there is no praeangular notch on the basal part of the body, the mandible rocks like a cradle when it is placed on a table.

Outer surface of the body

A lateral view of the mandible shows that the lateral prominence at the posterior end of the body has two tori, the torus lateralis superior and the torus marginalis (Weidenreich, 1936). The former runs transversally in the middle of the body and ends at the mental foramen, while the latter runs along the basal margin to the pronounced anterior marginal tuberosity. Between these two tori, the intertoral sulcus is observable. The mental foramen is large in size (6 mm×4 mm) and is located below Pm2-M1.

The basal margin between the anterior marginal tuberosities is bent upward, making a fairly deep mental notch. At the middle of this notch the trigonum basale projects downward. Although the right half of the symphyseal part of the mandible is slightly damaged, the chin eminence is considered to be moderately developed.

Inner surface of the body (Pl. 2. 5, 1)

In medial aspect, the alveolar prominence rises sharply, overhanging the basal part of the body, and below this prominence the basal part recedes laterally to form a wide and shallow depression, as is usually seen in modern man. No mandibular tori are to be seen. The cross-section of the body behind M2 is inclined inward, in contrast to the perpendicular posture in Neanderthal man.

The linea mylohoidea runs without interruption toward the mental spine to connect with the torus transversus inferior which develops on the basal part of the symphysis. Also in the middle of the symphyseal region can be seen the torus transversus superior, which starts below Pm1 and runs transversely to that of the other side. Between the two transverse tori, there is a round depression 8 mm in diameter and 3 mm in depth. This depression is regarded as the fossula supraspinata or fossa genioglossi. According to Keiter (1935), the existence of this fossula is rare even in Australians and Melanesians. But it is found in Heiderberg, La Chapelle, Krapina, Shanidar and Amud man (Suzuki, 1970).  -Kramberger (1906) regards this fossula as a characteristic pithecoid in man. The digastric fossa of the basal surface of the body is an elongated oval in shape, measuring 16 mm mesio-distally and 5 mm labio-lingually; this is considered to be the same as the average size for modern man. The fossa on both sides meet at the median line, where the trigonum basale protudes downward.

-Kramberger (1906) regards this fossula as a characteristic pithecoid in man. The digastric fossa of the basal surface of the body is an elongated oval in shape, measuring 16 mm mesio-distally and 5 mm labio-lingually; this is considered to be the same as the average size for modern man. The fossa on both sides meet at the median line, where the trigonum basale protudes downward.

The rami of the mandible

The ramus is 56 mm high and 33 mm wide, and its index (56.9) indicates a much lower mandible than that in the average modern Japanese (53.1). The ramal notch is also shallower (index 37.1) than that of the modern Japanese (index 41.6). On the outer surface of the ramus, the masseteric area is covered with the marked impression of muscle relief and is especially deeply depressed around the gonial angle, where marked development of the masseteric muscle in Minatogawa I can be seen.

On the inner surface of the ramus, the well-developed crista endocoronoidea meets the crista endocoronoidea immediately above the mandibular foramen to form the high-elevated torus triangularis, which continues directly downward to the linea mylohyoidea. Between the torus triangularis and the oblique line of the ramus, we can see the very wide and deep fossa praecoronoidea (Klaatsch, 1909) or sulcus extramolaris (Weidenreich, 1936). The gonial angle curves markedly inward, suggesting that the internal pterygoid muscle is pronouncedly developed on the Minatogawa mandible.

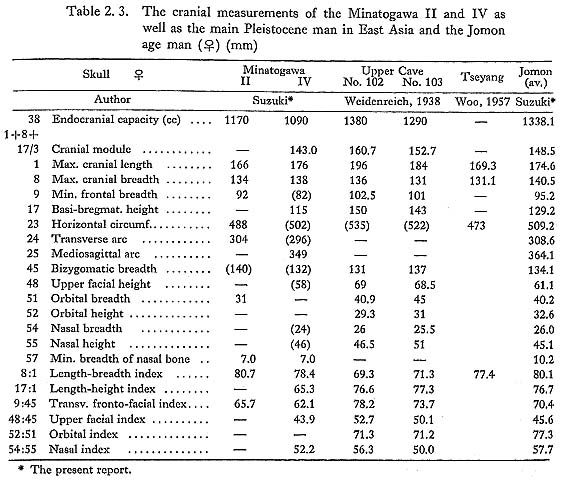

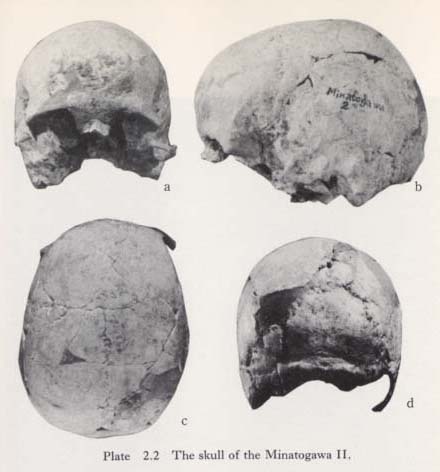

The skull of Minatogawa II (Table 2. 3; Pl. 2. 2; Figs. 2. 9 and 10)

The Minatogawa II skull is whitish-brown in color with dark brownish spots. The skull vault is nearly complete except for a large part of the nuchal plane of the occipital bone, the right zygomatic process of the frontal bone, the left zygomatic process and the mastoid process of the right temporal bone. The facial bones are broken off for the most part, except for the upper parts of both nasal bones, the frontal process of the maxillae and the upper part of the frontal process of the right zygomatic bone.

The Minatogawa II skull is very. small in size and has a smooth external surface. The forehead projects fully outward. The prominent supraorbital ridges, deep temporal fossae and massive mastoid processes may be regarded as primitive features of the skull.

The three main sutures of the skull are obliterated on both the external and internal surfaces, but are slightly traceable exocranially. Thus, the skull is considered to be that of a female individual of mature age.

On viewing the skull from above, a remarkable asymmetry can be observed, which will be described in detail below.

General aspect of the Minatogawa II skull

The skull as a whole is medium in size for the female sex.

The maximum length of the skull (166 mm) is short; the maximum breadth (134 mm) is also medium; the cranial index (80.7) is brachycranic. The basi-bregmatic height of the reconstructed skull (ca. 134 mm) is medium, but the auricular height (117 mm) is high.

The cranial capacity as measured by the millet seed method is 1170 cc. The cranial capacity of the modern female Japanese is 1368 cc on average, ranging from 1090 cc to 1660 cc. On the other hand, the average value for the Jomon age female is 1338.1 cc, ranging from 1150 cc to 1510 cc.

The Minatogawa II cranial capacity, therefore, is classified as small for recent female Japanese.

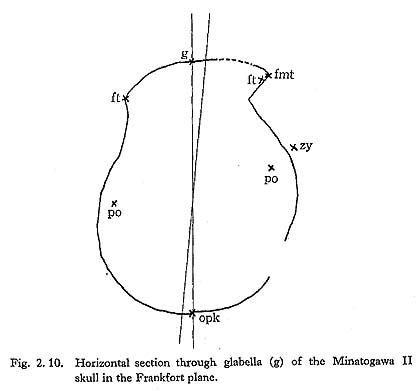

Norma verticalis (Pl. 2. 2, c; Fig. 2. 10)

The Minatogawa II skull is ovoid as seen from above.

The skull narrows anteriorly and, after showing a roundly flared forehead, turns abruptly, much like the Minatogawa I skull, lateralward to the very robust zygomatic process of the frontal bone. On the other hand, the skull widens posteriorly to form a round and blunt occipital region. Parietal tuberosities are not prominent on either side.

The sagittal, coronal and lambdoid sutures are traceable on the external tables of the skull but are fused entirely on the internal tables. No parietal foramen can be seen around the obelion region of the sagittal suture.

On viewing the skull from above, a remarkable asymmetry can be observed.

Setting the skull on the Frankfort plane, the frontal eminence and especially the zygomatic process of the right frontal bone project more anteriorly than the left ones, and the parietal eminence of the right side projects more lateralward and shifts more anteriorly than that of the left side. The left half of the occipital bone projects more posteriorly than the left one. Thus, the right half of the skull in general is projected more anteriorly than the left one. There is some doubt that these asymmetries are of natural origin. As stated above, the cranial sutures are almost completely obliterated, and all the skull fragments fit together perfectly. There is no evidence that the asymmetry was caused by external factors such as the unnatural connection of bone fragments.

In this respect, a bilateral difference is noticed in the angles formed by the meeting of the frontal and temporal surfaces of the frontal bone at the temporal line. The angle is 113° on the right side and 139° on the left side, as measured on the horizontal section through the glabella point. The distance between nasion-portions is 105 mm on the right side and 91 mm on the left side. In addition, the fossa temporales on the right side is much deeper than that on the left side. These asymmetries are considered to be not of natural origin but to have some pathological cause such as congenital or postnatal torticollis toward the left side.

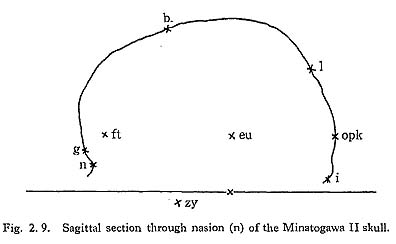

Norma lateralis (Pl. 2. 2, b; Fig. 2. 9)

The skull vault is nearly complete except for the right zygomatic process of the frontal bone and the large part of the nuchal plane of the occipital bone. A lateral view shows the prominent supraorbital ridge below the round forehead anteriorly and the blunt occipital region posteriorly.

The forehead is remarkably flared in hemispherical form. The inclination angle (g-b∠g-i) is 63°, which is nearly the same as the average value for modern female Japanese (61.2°), but the curvature angle of the frontal bone is 119°, which is less than that in modern female Japanese (128.2°).

The curvature of the parietal bone is pronounced, especially in the vertex region. The marked development of the occipital tori is recognizable on the border between the occipital and nuchal planes.

The temporalis line is remarkably well developed on the frontal and parietal bones. The temporal surfaces below this line are deeply depressed to form a more spacious temporal fossa than that usually seen in modern man. The anglus mastoideus of the parietal bone bulges lateralward to form a small, oval projection, which is considered to be the torus angularis. At the lower end of this temporal line, the crista supramastoidea projects prominently. The zygomatic crest is also high. The upper surface of the root of the zygomatic arc represents a broad groove widening anteriorly. Therefore, the zygomatic process of the right temporal bone, which is the only side preserved, comes to span the deep temporal fossa about 17 mm from the surface of the temporal bone; these characteristics also indicate the significant development of the temporal muscle of the Minatogawa II skull.

The mastoid process is as small as that usually seen in modern man, but it bulges lateralward; the supramastoid sulcus is rather well developed for a female skull. The external auditory aperture is round in form with a diameter of 8 mm. Two aural exostoses are observed on the posterior wall of the typanic plate of the right side. They are arranged up and down as ovoid, flattened prominences about 7 mm long, 4 mm broad and 1.5 mm thick (Pl. 2. 7, b).

Norma frontalis (Pl. 2. 2, a)

The most striking features of the Minatogawa II skull from the frontal aspect are the round but narrow forehead with the broad upper face and the well-developed glabellar region.

The robust zygomatic process of the frontal bone of the right side runs rather horizontally lateralward to connect with the frontal process of the zygomatic bone by means of the zygomatico-frontal suture.

The minimum frontal breadth of the Minatogawa II skull is 92 mm, which is almost the same as that in modern female Japanese (91.0 mm), but narrower than that in the Jomon female population (95.2 mm). On the other hand, the superior facial breadth is ca. 108 mm on the reconstructed skull, which is broader than that of modern Japanese (100.1 mm). The ratio of the minimum frontal breadth to the superior facial breadth is 85.2 in Minatogawa II, which is less than the value in modern Japanese (90.9). Thus, the Minatogawa II would probably have had an extremely broad upper face with a narrow forehead.

Of the facial flatness measurements of the reconstructed Minatogawa II, the IOW, subtense IOW, frontal index and nasomalar angle are 97 mm, 9 mm, 9.28 and 159, respectively. These figures suggest an extremely flat face for Minatogawa II.

Most of the orbital bones are lost, and only the upper part of the frontal process of the right malar bone is preserved. The orbital surface of this process shows a tendency to curve medially at a point only 7 mm below the zygomatico-frontal suture. This suggests that the orbita of the Minatogawa II must have belonged to the chamaeconch form.

The nasofrontal suture recedes markedly backward below the heavily developed glabella. However, the nasal root projects significantly forward.

The nasal bone is narrow and pinched in form. The minimum width of the nasal bone is 7.0 mm, which makes it much narrower than that in Jomon age females (10.2 mm) and the same as that in modern Japanese (7.1 mm).

Norma occipitalis (Pl. 2. 2, d and Pl. 2. 6, b)

The Minatogawa II skull is round in occipital view; the parietal tuberosities are thus not easily distinguishable.

The occipital plane of the occipital bone is very much intact, but a large part of the nuchal plane is lost. On the border between the two planes, well-marked occipital tori are visible. These tori consist of two lateral tuberosities and a connecting lineal portion between them.

The tuberosities indicate a spindle-like form about 35 mm in length, 14 mm in breadth and 3 mm in thickness. The tuberosities extend lateralward forming low ridges, which disappear near the occipito-mastoid sutures. The lineal portion is 8 mm in both length and breadth and 1 mm in thickness. The external occipital tuberosity is not seen above the lineal portion; instead there is only a rough surface. A faint lineal furrow 63 mm long runs along the upper margin of the tori.

The digastric fossa (or incisura mastoidea) of the Minatogawa II skull is not narrow like a cut, as it is usually seen in modern man, but a wide and shallow groove as in the Minatogawa I skull.

The Minatogawa III

The skull of the Minatogawa III is lost entirely.

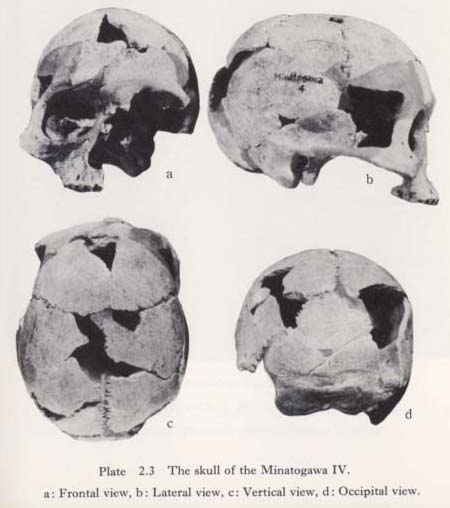

The Minatogawa IV skull (Table 2. 3; Pl. 2. 3)

The skull of the Minatogawa IV is colored brownish-white with dark spots and is in a good state of preservation owing to the mineralization of the bone.

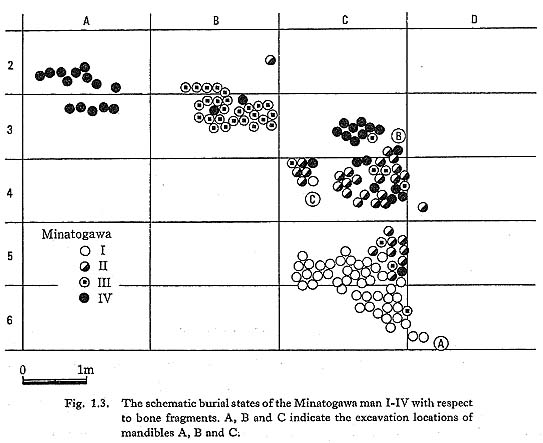

As stated already, the skull was found buried in fragments scattered over a wide area at the site (Fig. 1. 3). There are many sporadically missing parts of the skull vault and facial bones.

As to the cranial vault, the left temporal bone and both sphenoidal bones are entirely missing. In addition, the right zygomatic process and the right temporal surface of the frontal bone are largely broken off. The facial bones of the left side are entirely missing, and the bones of the right side are preserved except for the frontal and zygomatic processes of the maxilla.

The Minatogawa IV skull is small in size, and its surface is very smooth. The forehead is moderately projected anteriorward. The prominent supraorbital ridges and the massive mastoid processes may be regarded as primitive features of the skull as in the case of Minatogawa II.

All the teeth of the upper jaw are missing. The sutures are entirely open exo- and endocranially. Consequently, the Minatogawa IV is considered to be a young adult female individual, probably less than 25 years of age.

General aspect of the Minatogawa IV skull

The skull as a whole is small in size, even taking into consideration the fact that it is a female skull.

The length of the skull (176 mm) is medium; the maximum breadth (138 mm) is medium; the cranial index (78.4 mm) is mesocranic. The basi-bregmatic height (115 mm) and the auricular height (104 mm) are both extremely low. The cranial capacity (1090 cc) is small.

The cranial capacity of the Minatogawa IV skull is much less than the average value in modern Japanese (1368 cc) and in the prehistoric Jomon population (1338.1 cc), but coincides fairly well with the minimum range value in both modern and prehistoric populations (1090 cc and 1150 cc).

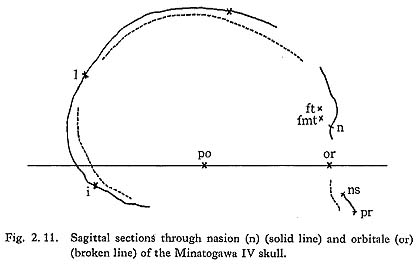

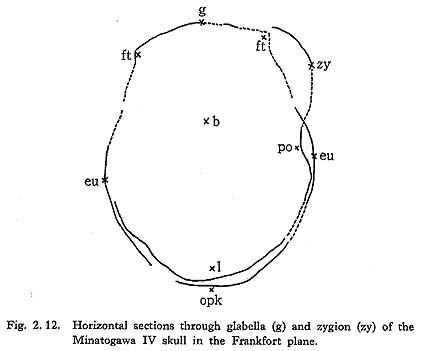

Norma verticalis (Pl. 2. 3, c; Fig. 2. 12)

The skull IV is pentagonoid as seen from above. The parietal tuberosities are slightly prominent, and the maximum breadth of the skull is between the tips of the tuberosities. Its position, expressed as a percentage of the maximum length, is 53.9%, which corresponds to that of 54.8% in modern Japanese.

The most striking features of the Minatogawa IV in norma verticalis are the forward swelling of the supraorbital ridge and the lateral projection of the zygomatic process of the frontal bone.

In the vertical view, the skull narrows anteriorly, then turns abruptly lateralward to the zygomatic process, which is much more robust than that of modern man. The markedly well-developed supraorbital ridge projects forward in rhomboidal form.

All the cranial sutures are open on both the external and internal tables; they look simpler in sutural dentation than those in modern man. A small parietal foramen is found on the left side of the obelion portion of the sagittal suture.

The contour behind the level of the maximum breadth of the skull is counterrhomboidal in form owing to the backward projection of the occipital squama.

Norma lateralis (Pl. 2. 3, b; Fig. 2. 12)

A lateral view shows a very prominent supraorbital ridge at the front and a roundly projected occipital behind.

The forehead is moderately inclined and swollen. The inclination angle (g-b∠g-i) is 60°, which is nearly the same as the average value for modern female Japanese (61.2°), but the curvature angle of the frontal bone is 134°, which is a little more than that of modern female Japanese (128.2°). The curvatures of the parietal and occipital bones are rather strong. Marked occipital tori are observed on the border between the occipital and nuchal planes. The temporal line is clearly recognizable on the frontal and parietal bones. Both the supramastoid and zygomatic crests are strikingly developed for a modern female individual. The external auditory meatus is round in form with a diameter of 10 mm. Three aural exostoses are observed on the wall of the auditory meatus of the right side. They are arranged successively from the anterior wall of the meatus to the posterior wall, showing round, flattened prominences about 6 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness (Pl. 2. 7, a).

The mastoid process is rather large in relation to the size of the whole skull and bulges lateralward. The digastric fossa is narrow like a cut, as it is usually seen in modern man, but short, since it never reaches the mastoid foramen.

Norma occipitalis (Pl. 2. 3, d and Pl. 2. 6, c)

In posterior view, the Minatogawa IV skull is oval in outline, and we can see the well-developed supramastoid crest and the massive mastoid process as well as the supramastoid sulcus between them. The muscle reliefs of the occipital bones are heavily developed, especially on the nuchal plane. In the bordering area between the occipital and nuchal planes, occipital tori, like those in the Minatogawa I and II skulls, can be found.

The tori, very much the same as those on the Minatogawa I and II skulls, consist of two oval tuberosities and a connecting lineal portion between them. The external occipital tuberosity is not visible, but instead there is a shallow, rough-surfaced, crescent-shaped depression just above the connecting portion. This depression corresponds also to the fossa suprainialis. The tuberosities extend lateralward, forming sharp ridges which disappear near the occipitomastoid suture.

Norma frontalis (Pl. 2. 3, a)

The most characteristic features of the Minatogawa IV skull from the frontal aspect are the semicircular contour of the cranial vault with narrow forehead and well-developed supraorbital ridge, the broad and flat face and the low orbit.

The glabella and supercilliary arc are confused into a rhomboidal supraorbital ridge, which stretches upward as a faint sagittal crest to the bregma. The zygomatic process of the frontal bone elongates horizontally lateralward to articulate with the frontal process of the malar bone. For this reason, the upper face is very broad in contrast to the narrow forehead. The minimum frontal breadth is estimated at about 82 mm from the reconstructed skull; this is much less than that in modern female Japanese (91.0 mm) and in the female Jomon age population (95.2 mm). The superior facial breadth, on the other hand, is approximately 102 mm, which is rather broader than that of modern female Japanese (100.1 mm). The ratio between the stated two breadths is thus 80.4 in the Minatogawa IV, much less than that of modern Japanese. The Minatogawa IV probably had a surprisingly narrow forehead with broad upper face compared to modern Japanese.

Judging from the reconstructed skull, the malar bone of the Minatogawa IV seems to be rotated more medially than is usually seen in modern Japanese. This medial rotation of the malar bone suggests the Minatogawa IV's wide and flat face. The bizygomatic breadth of the Minatogawa IV (ca. 132 mm) is broad, but the upper facial height (58 mm) is very low. The superior facial index is 43.9, indicating the extremely low-face type. The zygomatic breadth is larger than that of modern Japanese (124.9 mm) and a little smaller than that in the Jomon age population (134.1 mm). The upper facial height, on the other hand, is much less than that of modern Japanese (67.1 mm) and of the Jomon population (61.1 mm). The superior facial index is therefore much lower than that of modern Japanese (53.8) and even lower than that in the Jomon population (45.6). Thus, the Minatogawa IV seems to have had a very broad and low face compared to modern Japanese and probably compared even to the Jomon age people.

Of the facial flatness measurements of the reconstructed Minatogawa IV, the IOW, subtense IOW, frontal index and naso-malar angle are 96 mm, 9 mm, 9.38 and 158°, respectively. These figures suggest a remarkably flat face for the Minatogawa IV, like the Minatogawa I and II.

The malar bone of the right side is completely preserved but that of the left side is lost. The malar bone is small in size. Its maximum height was estimated to be 42 mm on the right side, its breadth ca. 38 mm. Both dimensions correspond to the low range in modern female Japanese. The malar tuberosity in the middle of the malar bone is only slightly developed, probably owing to the medial rotation of the bone as stated already.

The frontal process of the malar bone is short and stout, and its orbital border is so markedly curved medialward that the form of the orbit is considered to be of the camaeconch type.

Of the nasal root bones, only the nasal bones are preserved, though partly broken off. We can conjecture from the pieces of nasal bones that the Minatogawa IV possessed a narrow and fairly high nasal bridge, pinched in form. The minimum width of the nasal bone is 7.0 mm, which is much narrower than that in Jomon age females (10.2 mm on the average) and the same as that of modern Japanese (7.1 mm on the average).

The left maxilla is entirely broken off, and only the body and alveolar process of the right one are preserved. Judging from the reconstructed skull, the nose is considered to be low and wide. The canine fossa is shallow. The tip of the spina nasalis anterior is blunt. The lateral margin of the piriform aperature is sharp. It tends medial and downward and fades away on the alveolar surface of the second incisor. Thus, the anterior margin of the aperture does not indicate an anthropine form but rather an infantile form.

Perforation of skull in the Minatogawa IV (Pl. 2. 8)

On the frontal bone just below the frontal eminence of the right side, a small perforation can be seen. This perforation is nearly crescent in shape, and its concave margin directs downward. But, as can be seen from the inside of the skull, the internal table of the bone is roughly cut off along its concave margin. Thus, the width of the internal opening exceeds that of the external opening by nearly 10 mm on either side (Pl. 2. 8, b). The form and appearance of this perforation is comparable to that made by a gun. Consequently, the perforation is considered to be the result of some violent outside force, such as an arrow point shot from a high place to the forehead.

In this connection, three shallow bone injuries on the left parietal bone should be mentioned. Two are located just behind the parietal eminence, and the other is on the mastoid angle. They are all the same in shape and nature (Pl. 2. 8, c). They represent clearly circumscribed, nearly square breakage of the external table (3 mm × 6 mm). The depths of the breakages are about 1 mm but are especially sharp-edged, commonly in one corner. The breakages are considered to be the result of some violent force, which may have occurred at the same time as the perforation of the forehead of the skull IV.

Isolated skull fragment A (Pl. 2. 8, a)

The bone represents an isolated triangular fragment (30 mm × 30 mm) belonging to the left part of the occipital plane of the occipital bone containing the lambdoid suture. Its external surface is smooth, and it has a thickness of 5 mm in the center. No trace of sutural obliteration is observable. Most likely, the bone belongs to a young female individual.

As seen from outside, the upper margin of the fragment is concave, but seen from inside, the internal table of the bone is roughly cut off along its concave margin. Thus, the width of the internal opening exceeds that of the external opening by 6 mm on either side. This perforation is quite similar to that on the frontal bone of the Minatogawa IV skull. Consequently, the perforation is also considered to be the result of some violent force from the outside.