Shillacoto-Mito Period

As at Kotosh, construction found in Shillacoto in the stratum below that of the Wairajirca Period. We designated it S-R 7. Although this construction belonged to the oldest period chronologically, the techniques used in building it were of a most superior level and the scale was quite large. The style was basically the same type as had been discovered in the group of 'temples' at Kotosh, In other words the plan of the construction was square and the floor was divided in two upper and lower-levels. There was a hearth built in the center of the lower floor and it had a flue attached, However, this construction at Shillacoto has not been fully excavated and the whole plan has not been confirmed yet. The portion which was examined during the course of two excavations included the upper and lower floors, an outer wall on the west side which might have been a partition wall between constructions, an entrance on the west side and a corridor. It seemed probable that another construction existed on the west side of the corridor which corresponded to S-R 7 but proof of its existence was not possible as the plan of the floor could not be clearly defined. Whether this place was a corridor running around the outside of the temple or whether it formed another room like S-R 7 cannot not be ascertained.

In addition to the construction mentioned above, a floor surface which belonged to another construction was discovered beneath the floor of S-R. 7 and as well as this a further floor surface and the remains of a fireplace were found under that. Although the plans of all these constructions could not be known, from these facts we know that there were at least three constructions existed during the Mito Period at Shillacoto.

On the upper floor of S-R 7, a large lumber of Wairajirca style potsherds and. stone implements were discovered. Also a Shillacoto Shallow Incised potsherd was found in the middle of the hearth in S-R 7. However, apart from the fireplace, the lower floor surface had no potsherds in direct contrast to the upper floor surface and no archaeological remains were discovered at all in the earth used to make the lower floor surface. How can these facts be explained ?

Probably the following two conjectures are permissible.

a) The assumption that S-R 7 was a construction belonging to the Wairajirca Period.

We have excavated a large number of constructions belonging to the Mito Period at Kotosh and various other sites. There was a basic pattern of construction for all these so-called 'Temples', even. though there were a number of varia tions, and it continued without any major changes over a long period of time. It is not simply that the construction design and techniques were maintained for a long period but it might be that the people's way of life, their beliefs, the organi zation of politics and religions, their economic structure and all other cultural traditions in the Mito Period were also maintained for a long time. It is not true to say that this type of construction was invented during the Wairajirca Period. Therefore, in order to prove this assumption, we need a very convincting basis to work on.

One hypothesis is that the Wairajirca Period was the continuation of Mito Period and the culmination of this culture. To be sure, the time difference between the two periods is not so large nor is there confirmation of any great changes in their cultural content, so it might be that the Wairajirca Period was the extension and development of the Mito Period. However the most difficult point to prove in this hypothesis is that although the Wairajirca Period represents. the Initial Ceramic Period in this area, the quality of the pottery is so high that we cannot help thinking that there must have been a long tradition of pottery making technique to back it up. But this superior type of pottery appeared quite suddenly and no prototype of the Wairajirca-style pottery can be found in the in the Mito Period. On the contrary, no potsherds can be found that belong to the Mito Period. The origin of Wairajirca-style pottery is still unclear, therefore this assumption cannot emerge from the realm of hypothesis until further material evidence is discovered which can prove the direct relationship between the Mito and Wairajirca cultures.

Next we can assume that the people of the Wairajirca culture already knew the techniques of pottery making and came from another region to settle in. this area, and were influenced by the previous inhabitants who were of the Mito culture, gradually becoming assimilated acquiring their methods of temple con-struction. This hypothesis is based on the idea that the temple of Shillacoto was. built as a result of this assimilation. However if this hypothesis is true, both cultures must have coexisted at a certain period. To hold such an opinion regarding the assimilation and coexistence of the two different cultures merely because the constructions and pottery where discovered together is in our view too weak a basis. It is true that a large number of Wairajirca Period artifacts. were discovered on the surface of the upper floor but very few artifacts were foundon the lower floor surface. As far as this contradiction presented by the facts. of the excavation itself cannot be solved, once again we hesitate to state categorically that S-R 7 is a construction of the Wairajirca Period even without considering the previous hypothesis above. In order to prove any of the above views regard ing this assumption, a great deal more evidence will be necessary.

b) The assumption that S-R 7 was a construction of the Mito Period but was also used during the Wairajirca Period.

For us this assumption is more reasonable. S-R 6, a construction of the Wairajirca Period, was built on a new floor which buried the lower floor of S-R 7. The lower floor of S-R 7 was not completely buried but about 20-30 cm. was left. In other words, during the Wairajirca Period, the 2-step, upper and lower style, floor surface was still in use. A large number of potsherds, stone implements, etc. of the Wairajirca Period were discovered on top of this newly laid floor surface just as in the case of the upper floor surface. When we examined the vertical wall between the upper and lower floors of S-R 7, we found several niches which appeared to have been built into it (Fig. 9. See Chapter on Excavations). We had previously found an example with many niches in the wall of the lower floor at the Kotosh site, and we had named this construction "Templo de los Nichitos" on account of these niches. At Kotosh, this construc tion was built on top of the buried "Templo de los Manos Grusados" and was situated stratigraphically at the uppermost layer of the Mito Period culture, directly below the Wairajirca cultural stratum. No pottery was discovered in this construction. In the case of Shillacoto, S-R 7 was located directly beneath the Wairajirca culture layer and thus S-R 7 and "Templo de los Nichitos" are in general correspondence stratigraphically. At Shillacoto, if the people intended to go on. using S-R 7 during the Wairajirca Period, it might have been necessary to restore, strengthen or rebuild the constrauction. The places in the wall of the lower level, where the niches appeared to have been constructed, were actually packed with stones, which we theorize as either being the result of restoration to use the upper floor during the Wairajirca Period or the stones had been placed in the niches to prevent to lower wall from collapsing. Also we believe that this strengthening or restoration of the wall was done before the laying of the lower floor and there is a possibility that during this work that some small products became mixed in. We assume that the small number of Wairajirca potsherds discovered in and around the remains of the hearth in S-R 7 were the result of this process. Therefore, it is too premature to assume that the Mito and Wairajirca Periods are the same merely on the basis of finding pottery in S-R 7 but in this case, we think it is more reasonable to think that the Wairajirca Period culture used the construction of the preceding Mito culture by restoring and rebuilding them. As to the degree of restoration or rebuilding, this is a very difficult thing to judge because S-R 7 has been extensively ruined. As mentioned above, this construction has not yet been fully excavated so that these problems are left to be solved in future excavations.

Fig. 9 |

We tried to weigh the facts using the two hypotheses, 'a' and 'b', presented above. Of course, we believe there to be more varied interpretations than just these two. Whichever proves to be correct, clarification of the relationship between the Mito and Wairajirca Periods is extremely important in thinking about the origins of the Formative Period Culture and agricultural civilization in the Andes region. Nevertheless, there few examples in which the two cultures are situated as closely stratigraphically as is the case at Shillacoto, although it might be that the two are much more closely related than had previously been thought. It is necessary to investigate this question more deeply now and in the future.

Shillacoto-Wairajirca Period

The outstanding features of the Wairajirca culture at Shillacoto were the magni- ficently-built tombs and the extremely rich variety of potsherds. The tombs were constructed by piling up finely dressed stones. In the case of S-R 6, a final coating of white colored clay had been applied to the wall surface on the inside of the burial chamber. In addition, the lower part of the inner wall had been decorated with red paint on the white colored coating. As mentioned above, S-R 6 was built on the newly laid floor which buried the lower floor of the Mito Period construction S-R 7. Actually, S-R 6 was the only case in which the inner portion was excavated but there were two other constructions, S-R 13 and S-R 19, which resembled it in outward appearance and both of these were built on the upper floor of S-R 7. The fact that such fine tombs had been built during the Wairajirca Period was ompletely new and caused great excitement. From this, we also know that the custom of burying the dead with care and warmth was in existence at that time. From the results of our excavations, it is known that these altar-style tomb constructions appeared above the surface of the earth in those days, so it is possible to think that this was not a place for normal daily life but was in reality a special sacred place. Also we can imagine that the people who were interred here were not ordinary ones but belonged to a special class, for example the chief, or the priest or some other powerful personage of those times. From this, we can deduce that there was already some differentiation and classification of position and status within the hierarchy.

Whith regard to pottery at Shillacoto, there were a large number of superior objects in terms of both quantity and quality and they were each made very elabo rately which leads us believe that this earthenware was not used only in every day life. Accordingly, we feel that the pottery was connected in some way with the tomb constrauctions mentioned previously, and that some special celebrations or functions seemed to have been held and there were some signs that the magni ficently decorated pots were especially produced for use in these rituals.

The special characteristic of Wairajirca pottery at Shillacoto was the extremely wide variety in both shapes and patterns. For example, there were neckless jars, short-necked globular jars, long-necked bottles and various kinds of bowls. As examples of special shapes, there were a deep bowl with triangular mouth, a deep bowl with lateral flange, a boat-shaped vessel, a kidney-shaped bowl, a long necked bottle with double rounded shoulder, a double spout jar and so on. Also the shallow bowl with handle which was quite rare at this time. Of the more normal shapes, there were carinatcd bowls, bowls with convex sides or vertical sides. Especially remarkable were the decorations found on the pottery, in which figurines with faces of cats, monkeys, birds and human beings were used in appliquée; decoration on the mouth or body of the ware. These figurines were shaped using modelling techniques and the features, such as eyes, nose and mouth, etc, were represented by incision or punctation. This type of appliqué was especially common on fine quality ware such as the Black Polished Incised or Brown Polislied Incised types.

The deorative techniques used on these ceramic ware wares included zoned hachure, punctation, impress, broad-line incision, fine-line incision, excision, post fired painting, etc. Decoration motifs were drawn from various geometric patterns, such as circle and dot, circle, rectilinear line, triangle, step design, semi-circles, etc., and some of these appeared combined.

In addition to the pottery, a large quantity of other ceramic artifacts were produced. There were also stone implements, such as chipped projectile points, Tsshaped polished stones axes, polished spherical club heads, stone knives, stone pendants, stone bowls and plates, round manos and metates, stone pestles, jet mirrors, etc. All of these were well polished and of exquisite workmanship. Especially, the mirror discovered in S-R 6 was a masterpiece. The bone objects were spatulas, awls, spatula-awls, needles and a whistle. In addition, there were a large number of products such as ceramic human, animal and bird figurines. However, independent figurines of animals were quite rare and we think that they were mostly used as appliqué decorations for the pottery.

We could not find any direct evidence of ordinary dwellings or the cultivation of plants during the Wairajirca Period at Shillacoto, but considering the magnificence of the tombs and the degree of development and variety of earthenware and stone implements and other tools, we can almost assume with confidence that the .stage of civilization had progressed in this period from a food-collecdng economy to that of a settled agricultural life.

Shillacoto-Kotosh Period

The constructions of this period were divided into two main categories on the basis of construction method and plan. One type was of a circular or semi-circular shape and used small boulders and breccia in the construction, of the walls. S-R. 1,2 and 3 belong to this type. The other type had a square plan with walls of finely dressed stone, S-R 11 and 12 belonged to this type. The former type was located on the east side of the remains and the latter on the west side and each of them, formed a different group of constructions. These groups of constructions were on different levels stratigraphically with the first group being high and the second group being low. However, the stratigraphic difference between these two sets of constructions did not indicate a chronological difference because they were located far apart and were not directly on top of each other. We could not confirm whether these two groups of constructions were independent of each other or whether they were connected by a staircase or corridor. At least, we did not discover any staircaselike structural remains.

There other constructions in addition to the above such as the tomb of S-R. 4 (Tomb No. 4). This tomb was situated stratigraphically beneath the floor of a construction belonging to the Kotosh Period and used a wall of S-R 6, a Wairajirca Period construction. The west side of the tomb was strongly constructed from large dressed stones piled on top of each other and a square opening built in it. A lot of funeral objects or offerings were arranged inside the tomb. No other tombs. of this type were to be found, but the custom of conducting a careful burial had carried on into the Kotosh Period from the Wairajirca Period.

From the ceramic culture point of view, we can assume that the Kotosh culture continues on from and is a direct extension and development of the Wairajirca Period culture. The best proof of this is to be found in the vessel with representation of a human face which is clearly a development from the Wairajirca vessel with representation of a monkey face. Also a large number of elements of Wairajirca Period pottery, such as the deep bowl with triangular mouth, the deep bowl with lateral flange, the long-necked bottle with double rounded shoulder, the carinated bowl, etc. and the technique of post-fired painting, were carried on in the same form in pottery of the Kotosh Period, On the other hand, there were some new types which first appeared in the Kotosh Period. For example, the shoe shaped vessel, the stirrup spout jar, graphite painting and so on. Compared with the Wairajirca Period, decoration techniques such as zoned hatchure and fine line incision showed a decrease while broad-line incision and groovcd-line incision increased, and geometric patterns that had more space between the motif became more popular. It is also remarkable that the representation of human beings in this period was extremely realistic.

The most important and noteworthy archaeological remains discovered at Shillacoto for this period were the bone objects with the incised design of a feline motif. Especially as the design in which the upper and lower fangs are clenched together had often been found on stone carvings such as ' Lanzón ', the ' Comisa de los Felinos ' at Ghavin de Huántar and others and tills discovery clearly indicated the relationship between the Shillacoto-Kotosh culture, which was a pre-Chavin period and the Ghavin culture itself.

Most of the stone implements were direct continuations from the previous period. For example; chipped stone projectile points, polished stone axes and knives, club heads, stone bowls, manos and metates, jet mirrors, stone figurines, pendants, etc. However there were some slight differences in size and shape. For example, the stone knives changed from rectangular to semi-circular shape and the club heads became smaller. Also this period saw the production of superb jet mirrors and one specimen was very well preserved with a briliant polished surface in which images could actually be reflected. In addition to the bone objects mentioned above, tube-shaped artifacts, spatulae, awls and needles were also produced. The surface of the tube-shaped bone objects had been carved with small human faces and geometric designs such as circle and dot and vertical line ending with dot. The Kotosh Period was the first instance of their appearance and is worthy of mention. There were also clay figurines depicting human beings or animals which confirmed the tendency toward more realistic representation.

The Kotosh Period is thought to have been the continuation of the Wairajirca Period and in this period ordinary dwelling places were built and we can judge that a settled life was definitely being carried on. No material was found to prove the cultivation of plants but we believe that agriculture itself had already started. Bone remains, among which were of llama, deer, kui (a type of marmot), bird bones and shells, were discovered and may well have provided part of the food source.

Considering the elements of the Kotosh culture in their entirety, it is shown to have a very close relation to the Chavin culture. At Kotosh, the Ghavin Period culture followed on directly after the Kotosh Period culture but at Shillacoto no indications of this were to be found. However, the distance between Kotosh and Shillacoto is only 5 km. Although the situation is like this, what reason could there be for such a large and important cultural discrepancy between them. Whether the Kotosh culture formed the basis from which the Ghavin culture was born or whether in the early stages the two cultures existed independently in parallel is a question we cannot answer. This point is one of the most important subjects for study with regard to the investigation of the origin of the Ghavin culture and will continue to be so in the future.

Sliillacoto-Higueras Period

Artifacts were to be found over the entire area of the excavations but those architectural remains which were definitely part of constructions were mainly in zone E. The constructions were composed of two, an upper and a lower, strata and in this case the upper layer constructions and the lower level constructions were placed on top of each other in the same place, so we divided them into two sub periods. However, with regard to the artifacts or the construction methods, it was very difficult to differentiate between the two sub-cultures. The construction which belonged to the Upper Higueras Period is S-R 8 and those of the Lower Period arc S-R 9 and 10. The walls of the constructions were made up of a mixture of dressed stones and riverbed stones and the plan of the room was square shaped. However, we could not study S-R 8 with much accuracy as it was extensively destroyed.

The special feature of the Higueras Period was the large number of tombs constructed. The style of tomb was to make a small stone cist by assembling thin micaschists or flat stone slabs and the form of burial was one body in one tomb (known as a single-burial tomb). The tombs were always constructed under the floor or in the wall. However the state of preservation of the bones was very bad, but we can deduce from the size and shape of the tomb that the burial style was with the legs folded and the head tucked in. We did not find any funeral offerings except in a small number of tombs. There were no really noteworthy artifacts amongst the potsherds, the stone implement and so on as these were almost identical to those preciously found at Kotosh and the surrounding area.

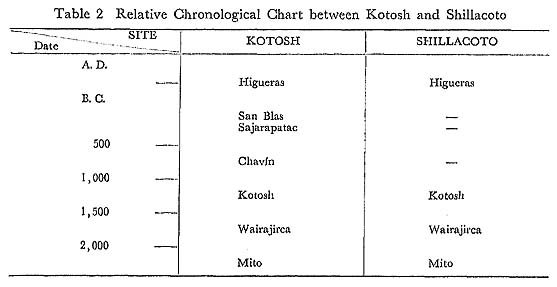

The exact dating of those cultures mentioned above which were discovered at Shillacoto has not yet been confirmed by C14-dating, but we think that they will fit into their relative chronological positions and will correspond to those other cultures discovered at Kotosh.

The special features of the Formative period culture as discovered in Kotosh, Shillacoto and other sites in the Huallaga River basin on the eastern slope of the Andes were similar in many ways to cultures in other areas which developed at same times. Therefore, we do not simply believe that these cultures were only limited local cultures developed in the Huallaga River basin but that it is necessary to investigate them as part of a chain of development of the Formative period culture of Nuclear America which stretched widely over the Andes and Meso america. This line of thought has already been commenced by several researchers. It has not been touched on in this manuscript but we intend to deal with it soon in the report covering the archaeological remains.